Cities moving ahead with pre-approved house plans

The nation faces a housing crisis, with a deficit of 2.3 homes nationwide pushing up prices in many markets—even in the nation’s heartland. “There is a gap between the supply of homes and the number of households that want homes,” and that gap is getting bigger, says Jennifer Krouse of Liberty House Plans.

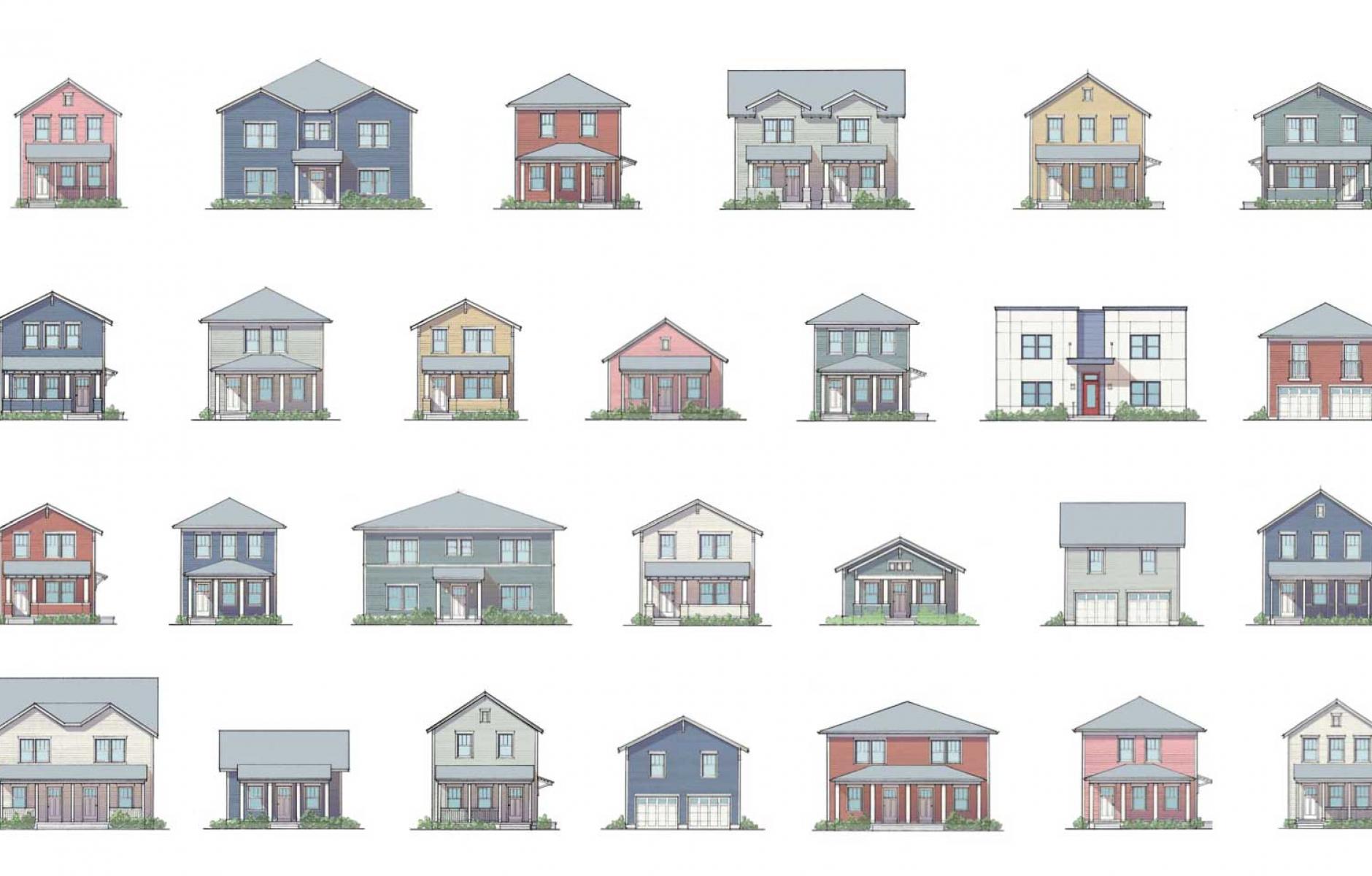

A growing list of communities nationwide are starting to adopt pre-approved building plan programs to address that issue. Pre-approved building plans, sometimes called “pattern zones” if they are used in a specific area of the city, allow a city to greatly expedite permitting for a set group of designs—which often are based on the region's vernacular architecture. These programs are in their infancy and have little track record, but they appeal to local officials for several reasons, according to a webinar panel on Challenges in Pre-Approved Building Plans hosted by CNU’s On the Park Bench.

“One reason why they are popular is that these programs are politically neutral and quicker to implement than some of the structural problems we face, like increasing the cohort of contractors who build or reforming zoning,” says Krouse, who is working with a number of cities to set up programs.

“Every city hall that Strong Towns is visiting across North America has an interest in pre-approved building plans,” notes Edward Erfurt, Director of Community Action at Strong Towns. He explains that pre-approved building plan programs align city hall interests with local developers, initiating a conversation around a delivery process for housing. “When you have the site planner, building official, fire marshal, and utility company all at the table, looking at the same plan with the common mission to develop a house product in your community, the game changes,” he argues.

Many terms are being used to describe a variety of similar programs: pre-reviewed, permit ready, stock plans, and plans catalog, among them, notes Allison Thurmond Quinlan, principal architect and landscape architect with Flintlock LAB, who worked on pre-approved house plans in Northwest Arkansas. She explains that pilot programs have struggled to meet the goal of plans that are “ready to build,” where you can walk into city hall, pay a fee, and get a stamp the same day.

“It’s almost impossible to get somebody to build a stock plan with no changes,” Quinlan says. “What amount of wall moves and bathroom layout changes can happen before the plan is changed too much? … It is psychologically difficult, even for developers, to not want to tweak plans. Flagging that as a reality and building some flexibility into the programs can be helpful.”

The panel described benefits of pre-approved plans.

- They allow the community to become more familiar with missing middle housing types, like small apartment buildings, duplexes, and accessory dwelling units, haven't been delivered in great quantities for many years.

- They encourage higher quality design so that small developers proposing similar projects will have an easier time. If housing is expedited, there is a risk that low-quality design will boost opposition. A collection of context-sensitive building plans offers greater predictability because the architectural review is complete, Krouse says.

- The programs are designed to reduce regulatory friction in a housing delivery system that many people recognize is overly complex. This helps to level the playing field between small and large developers, the latter of which have developed ways around bureaucratic red tape.

Krouse also identified challenges.

- The community has to choose a set of designs, which requires the planners to place a bet on which ones builders will like. There are ways to reduce the risk of making the wrong bet (have similar designs been popular and buildable elsewhere?).

- The builders often work with unfamiliar designs, which poses a financial risk at the outset.

- A pre-approved building plan exposes flaws in a town’s approval process. That’s good, but it could be difficult for departments or officials, who may discover they are the source of bureaucratic problems. “If you are a regulator, you have to make sure you are not the one getting in the way,” notes Krouse.

One of the most watched programs is expected to roll out in Spokane, Washington, on the first of March. Spokane will include two duplexes and two townhouses, and the city may explore plans for accessory dwelling units, says Krouse. Other cities with programs include South Bend, Indiana, Bryan, Texas, and Claremore, Oklahoma.

“If we analyze the programs that are out there, they are all still in their infancy, but they have taken the most important first step of engaging in this conversation,” says Erfurt.

What the whole webinar:

This article addresses CNU’s Strategic Plan goals of working to change codes and regulations blocking walkable urbanism, and growing the supply of neighborhoods that are both walkable and affordable.