Vision plan released for transforming I-81 in Syracuse

Syracuse and the New York State DOT are moving ahead with plans to demolish the aging I-81 viaduct through downtown and restore a “community grid.” Until this week, what that means has not been entirely clear.

Syracuse is now releasing its Community Grid Vision Plan 2024, which offers ideas for transforming streets and public spaces while moving the Interstate, which has long divided and overshadowed the city center, to the current I-481. The plan, presented in open houses this week, goes beyond addressing the immediate corridor to encompass seven neighborhoods, districts, and corridors forming the “community grid.” That broad city planning approach distinguishes I-81 in Syracuse from other freeway teardown projects around the US.

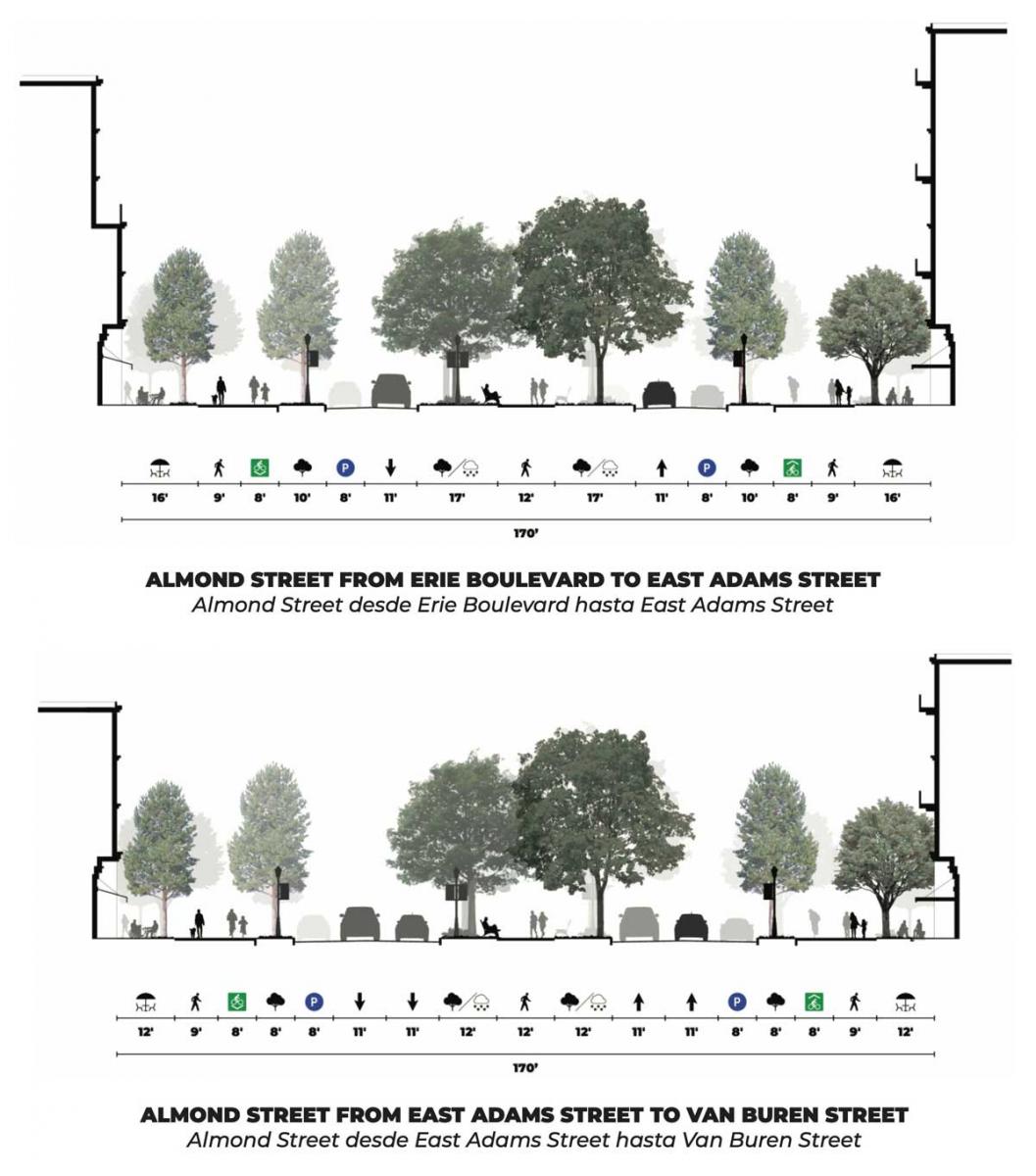

While the bulk of through traffic will be diverted around the city, the grid will still be traversed by Business Loop 81, which would travel along Almond Street through the downtown area. The plan calls for Business Loop 81 to have the character of a city street. For many blocks, the plan shows a 45-foot-wide tree-lined park in the center of the street (see rendering at top). “A great street is designed in inches, relative to the human scale and sets the foundation for thriving neighborhoods to build relationships, participate in the economy, and live an active, healthy life,” the planners note. “A great street, like Almond Street can be, makes better lives for those who live with it.”

A key aspect of the plan is to create a better interface between the transformed highway and the city. The interface is an essential element of urbanism, a field where the New York State DOT has little experience. DOT builds highways and bridges, and they have few tools to adjust to urban context or enable building frontages supporting walking, biking, and street life. Images shown in DOT’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement poorly addressed that interface, key to restoring a “community grid” and meeting the needs of city residents.

Consequently, the City of Syracuse hired the Community Grid Vision Plan team, led by Dover, Kohl, & Partners, who hosted a week-long charrette in August, 2022. “The city assigned this team of planners, architects, engineers, and experts in the fields of housing, development, economics, and anti-displacement with the task of making sure the community’s voices and ideas for the Community Grid remained the guiding influence for the project until it’s final design and construction,” according to the document released by the city.

The plan looks at how the entire grid can be improved in the immediate area of the transformed highway. There are 10 key recommendations for Almond Street, the thoroughfare that will replace the current highway. The technical ideas aim to increase opportunities for walkable urbanism downtown and in adjacent neighborhoods, emphasizing affordable housing.

Travel lanes and design speed will determine part of that character, but so will architecture, building frontages, and a pedestrian-oriented right-of-way adjacent to the automotive route. Knowing that DOT holds sway on the travel lane design, the city seeks to influence the adjacent character and interface as much as possible. That approach was taken throughout the study area.

“Community Grid streets are identified corridors that should be reconfigured to improve safety, connectivity, and/or development within the study area,” the planners note. “For example, adopting a ‘complete street’ plan, a one-way to two-way conversion, reducing lanes or lane widths, re-establishing a vacated street, or planning a new street.”

The plan strongly emphasizes transit-oriented development, built around a planned Bus Rapid Transit line. One proposal states: “Placing a high-ridership bus station within the core of a higher-potential development scenario is a key element of transit-oriented development strategies—and only increases the odds of success for both.”

Due to a lawsuit filed by opponents, the plan was under a legal cloud for a year and a half. This hampered the city’s ability to share renderings and plans publicly, so this plan lacked the typical feedback loops of a new urbanist charrette. The city is releasing the plan now that the legal challenge was overturned. In recognition of that situation, the mayor makes a point of soliciting ongoing public feedback. “A vision plan is, by nature, a living document, so we still want your input,” says Mayor Ben Walsh in a brief introduction to the plan.

This article addresses CNU’s Strategic Plan goal of growing the supply of neighborhoods that are both walkable and affordable.