Dabbawalla: Low-carbon urban delivery

Every visit to Bombay (Mumbai) renews my fascination with the service that delivers home-cooked lunches to office workers. The service is provided by Dabbawalla, which literally translates to “one who carries a box,” a tiffin, a modular stainless steel lunch container. For the past 134 years, they have delivered meals five days a week.

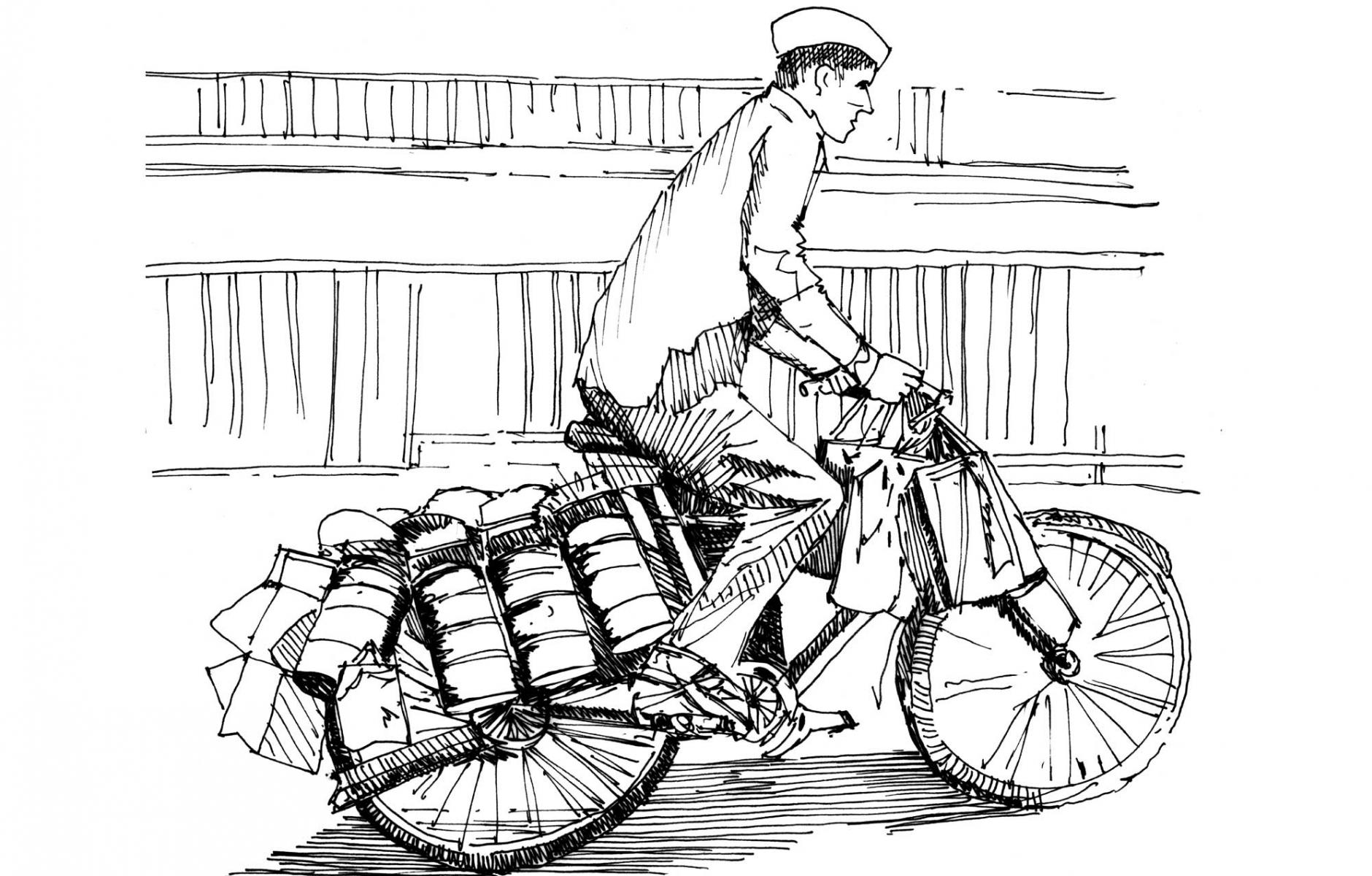

The Dabbawallas offer inspiring lessons. Their disciplined delivery system has always incorporated efficiency and sustainability. They rely on human-powered handcarts and bicycles, and existing surface mass transit—the 170-year-old Mumbai rail system, which serves as the umbilical cord connecting the city from the north to the south.

Mumbai production increased substantially in the 18th Century with the foundation of cotton mills, trading spice houses, and an expanded port. By the mid-19th Century, the city was overrun with migrants from other parts of the country looking for well-paying employment. At the time, India was a collection of royal principalities and states, each with its customs, cultures, languages, and cuisines. Hence, migrant's palates were attuned to their preferred tastes, only satisfied by home-cooked meals. Furthermore, the new workforce lived on the more affordable outskirts of the city and away from their center city workplaces. They had to leave their homes early in the morning and could not afford to buy lunch daily, often resulting in going hungry all day.

In 1890, an entrepreneur, Mahadeo Havaji Bachche, saw an opportunity to start a lunch delivery service with a workforce of a hundred men. The methodically organized service succeeded and has grown to more than 5,000 Dabbawallas, delivering over 130,000 lunchboxes daily.

The typical patriarchal society, commonplace in India, required the spouse to wake up and prepare morning tea and breakfast for her husband and children. Following their departure to work and school, she would start preparing a home-cooked meal for the husband’s lunch, which would take a few hours. A Dabbawalla would pick up the filled tiffin from home by 10 a.m. and start the complex journey to deliver the lunch to the husband’s workplace. Six Dabbawallas handle each tiffin before it reaches its destination. Men and women in the workforce without families or households where all adults work can employ a food service agency or individual contractor to prepare lunch to meet their appetite and accustomed taste and have it delivered by the Dabbawalla service.

The traditionally male Dabbawallas are related to one another and belong to the Varkari sect in Maharashtra State. They originate from a small village some 150 kilometers southeast of Mumbai. The network consists of two levels, foremen and delivery men, who start their apprenticeship between the ages of 15 and 20. Although the compensation is low, approximately $100 a month, with long hours and physical exertion, the fraternity enjoys the mutual benefit and camaraderie of working with relatives. Understanding their responsibility to the city’s workforce, who are dependent on their service, they only take one week off during the year when they all return to their village to celebrate a religious holiday.

On a typical day, Dabbawallas pick up the tiffins in the morning from various homes and food service companies across the city and transport them by handcart or bicycle to the nearest train station. The tiffins are loaded on trains and sorted in the luggage compartment for destination stations. At the appropriate station, tiffins are unloaded, placed on a handcart or bicycle, and delivered to the various office buildings where recipients will enjoy a home-cooked meal. One would assume the recipient would carry the tiffin home, but that is not the case. After lunch, the delivery process is reversed, and the Dabbawallas return the tiffin to its rightful home.

The Dabbawallas adhere to a strict code of conduct and are fined for alcohol and tobacco use, being out of uniform, and absenteeism. Each Dabbawalla must wear a white cotton kurta-pajama uniform with a white Gandhi cap. Additionally, they must contribute a minimum amount of capital in the form of two bicycles and a wooden crate to transport the tiffins.

A unique aspect of the delivery service is the reductive symbols, signs, and color codes that identify pickup and destination, which are painted onto the top of each tiffin. These abbreviated symbols denote the collection point, a color code for the starting train station, a number for the destination station, and markings for the location, building, and floor.

The lunch preparation and delivery services are independent of each other. Families involved in preparing home-cooked meals contract with Dabbawallas for their delivery service. The increase in households where all adults work has led to many commercial lunch kitchens, also serviced by the Dabbawalla system. These kitchens offer well-balanced, calorie-conscious vegetarian and non-vegetarian meals. A standard vegetarian meal typically comprises two vegetable preparations, dal (lentils), rice, rotis (Indian bread), and a salad, with the menu changing daily. The meal cost is approximately $2, or a bit higher for non-vegetarian meals. Dabbawalla delivery charges range from $10 to $15 a month. The total expenditure for an individual’s meal from a lunch kitchen is less than $60 a month.

Ecologically, the pickup and delivery portions of the Dabbawalla system are independent of fossil fuel consumption, as they are accomplished through traditional, low-cost, and sustainable bicycle and handcart use. And the middle part of the journey takes advantage of Mumbai’s existing electric-powered rail system. However, the influx of mechanized food delivery services that emulate the West threatens the livelihood of these dedicated workers. Internal combustion two-wheelers use dirty, low-grade fuel and do not have catalytic converters due to their small size and low purchase cost, making them the worst polluters, emitting toxic gases and particulate matter that have been proven dangerous for human and environmental health.

The burgeoning number of these two-wheelers contributes 32 percent of air pollutants in Indian cities. Additionally, the unwarranted surge in car ownership within the limited road infrastructure has made city centers congested beyond imagination, less bicycle-friendly, and unsafe for pedestrians and cyclists. An astonishing Supreme Court ruling now mandates that the entire public bus fleet and taxicabs convert from toxic lead-containing fuel to cleaner Compressed Natural Gas (CNG). This progressive first-time transport sector reform may be in vain as the government needs more buses converted and manufactured to comply with this ruling. However, when and if achieved, much of the benefit from this reform would be lost if dirty-fueled two-wheelers continue to spew toxic pollutants.

Despite the competition from fossil-fueled two-wheeler delivery services, the Dabbawallas have continued to work sustainably, keeping costs low and avoiding unbearable Indian bureaucracy, licensing, and vehicle registration. Their hacking of the tedious officialdom system is admirable and should be applauded and emulated in future below-the-radar sustainable endeavors.

What is sorely needed is the reform of existing policies that invest in auto-centric infrastructure, which will eventually bankrupt the city’s finances. Discontinuing investment in private vehicle movement would allow redirection of these funds to support sustainable rail transit, bicycle, and pedestrian infrastructure. The custom of using human capital, which is abundant in India, and the low-tech solutions practiced by Dabbawallas can serve as an inspirational model to substantially reduce carbon emissions.