Competing against suburbia

If urbanists, academics, and planners agree that New Urbanism and Traditional Neighborhood Developments (TNDs) are the best form of residential development, why are so few projects actually being built?

For the past three years, I have been working as a partner alongside my dad as we design, develop, and construct Woodbury, an 82-acre TND in the college town of Moscow, Idaho. As I’ve progressed in my career over the past few years, the one question I kept coming back to was why this new urbanist style hadn’t caught on with developers, especially West of the Rockies. Why aren’t more projects being built? Is this a reliable and repeatable process? Can it ever compete against the efficiency of tract building? Here is what I have learned.

The same post-war pattern of suburban sprawl has continued to dominate residential development—in large part, this is a result of builders doing what’s always been done (as far as they know). However, there are other roadblocks that make TNDs difficult to develop. Entitlements are an uphill battle against governing authorities as developers go against established zoning and auto-centric civil engineering practices. And even if the developer gets city approvals for the desired street sections, setbacks, zoning preferences, etcetera, constructing these improvements is expensive. Alleyways and amenities, staples of good neighborhood design, quickly rack up the infrastructure cost before the first house is ever built. Additionally, with narrower streets, utilities (water, sewer, storm, electric, gas, internet, etc…) must be meticulously planned and designed. Even after getting a new code accepted by the city, many good designs have been neutered by the requirements and standards of utility companies which have their own setbacks, standards, and business practices. This level of coordination between city planners, civil engineers, architects, underground contractors, and utility companies is cause enough for many developers to throw in the towel on TND design or not even start down the road in the first place.

Capital is the key tool for developers. With millions of dollars on the line and investors demanding a financial return on a specific time horizon, you cannot blame developers for mitigating risk by following tried-and-true methods of development. So how can developers build TNDs and make it pencil for themselves and investors? Here are two potential solutions:

Solution #1: Longer return horizons

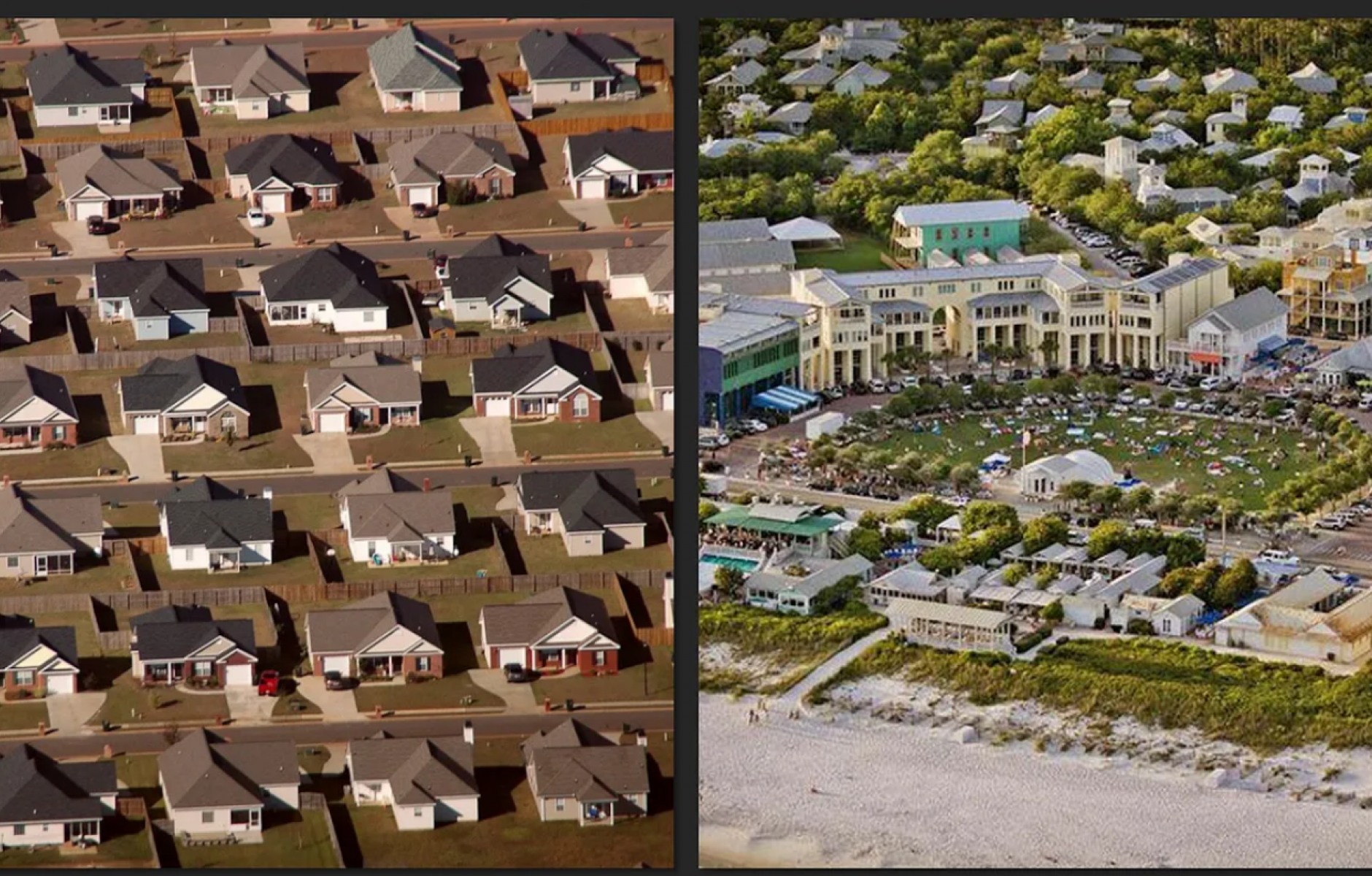

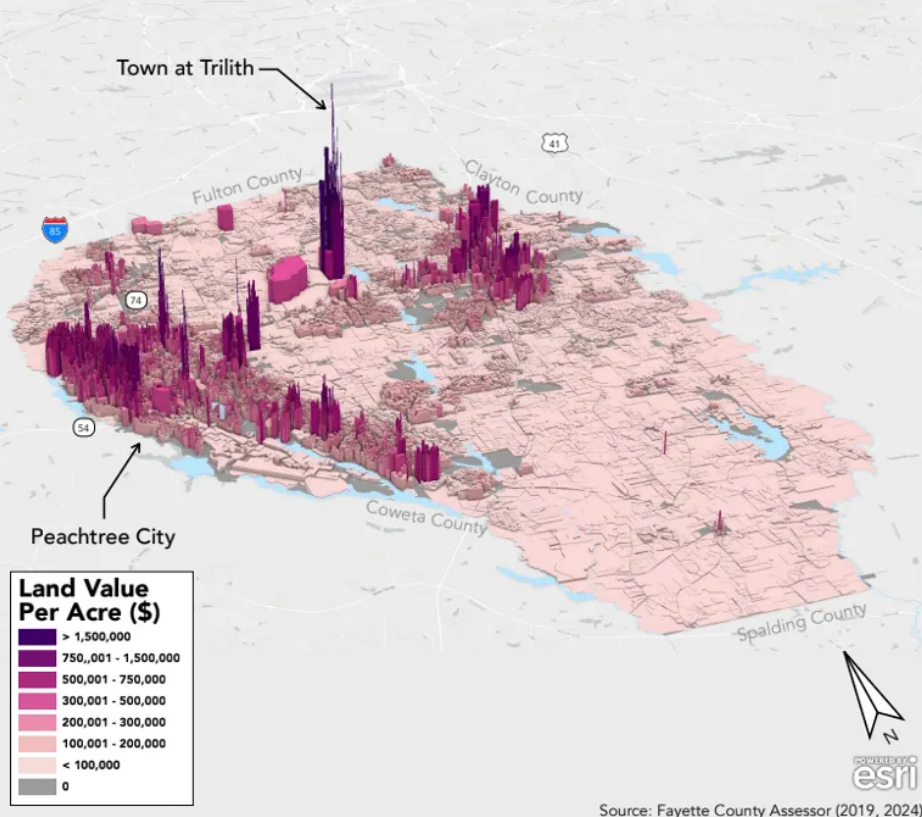

A developer has two options when working with a new piece of land. They can build quickly and efficiently using preset standards and grid-like block structure, focused on maximizing profits under quick timelines. Or, more preferably for TNDs, the developer can invest in the land by building something special and reap the rewards of that investment over a longer performance horizon. This relies on the idea of building equity rather than taking equity. This method of development lends itself to projects with a lifetime of 10 or more years. It does not lend itself well to builders who look at profits quarterly or annually with project lifetimes of 1-5 years. TNDs can’t compete with the efficiency of tract development. But with longer return horizons, the initial investment can compete and even surpass the returns of tract neighborhoods as the developer begins to sell their lots and/or homes for a premium. For this reason, some developers have latched on to the idea of doing New Urbanism, noticing that homes can sell for 20-40 percent more than other homes in the area while other TNDs like Trilith, Serenbe, or Seabrook (to name a few) are selling homes for 2-3 times the price per square foot than other homes in the surrounding towns.

Solution 2: Find an equity partner

With longer return horizons and oftentimes decade-plus project timelines, developers will predictably go through unpredictable recessions. When determining loans and timelines, remember that banks will always protect their own interests. Too often, if the ground gets shaky, they may demand their money back prematurely, which could strangle the project in its infancy and force the developer to sell. To survive these recessions, projects need backing from “patient money”, investors that have bought into the idea of building equity and believe in the vision. These are legacy projects and the majority of profits and equity will be seen in the later phases. Stakeholders should look to hold onto commercial areas and/or rentals as additional ways of securing their investment and gaining returns in the long run.

Anything good takes time

Developers face a difficult road with TND development. Great design, planning, and execution are essentials but ultimately it comes down to how the developer is able to manage their greatest tool, capital. Due to increased upfront costs, a slower regulatory process, and longer return horizons, developers need to find patient equity partners that are vision-aligned as to not put artificial pressure on the project that could result in sacrificing long-term growth for short-term gains. This model of Traditional Neighborhood Development works and is repeatable, but it is going to take a patient developer who can sell a vision to patient investors.

Note: This article first appeared in The ENU Exchange, a newsletter written by Emerging New Urbanist members about topics and debates within the movement. Subscribe to the newsletter.