Design for reduced carbon emissions and climate resilience

The Maplewood housing development in Ithaca, New York, was an exercise in new urbanist design that also meets aggressive greenhouse gas reduction goals. The project’s energy strategy aligns with Tompkins County’s “Energy Roadmap” to reduce carbon emissions by 80 percent over the next 40 years.

Maplewood, housing for Cornell graduate students, articulates primary elements of climate-responsive urbanism that push envelopes in energy and stormwater. Nearly doubling the site's density alleviates a local housing shortage, at least for the student submarket.

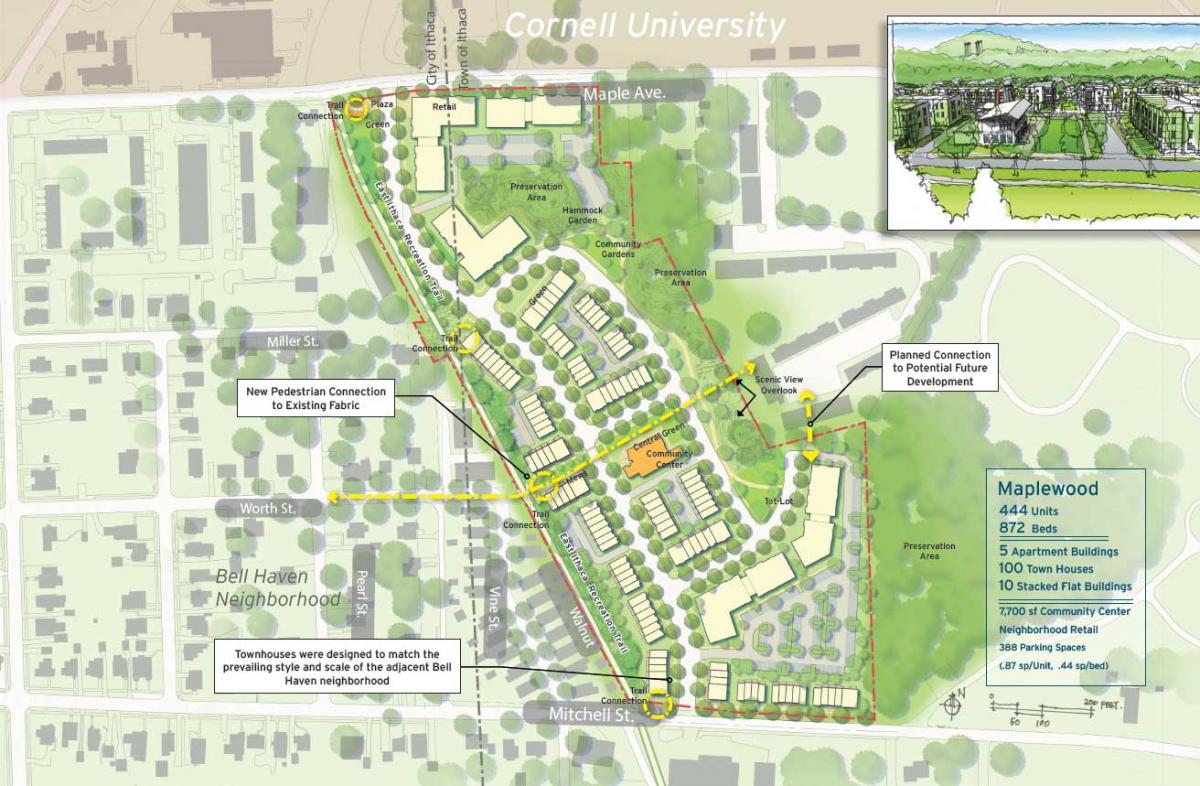

The 17-acre redevelopment provides 444 housing units (872 beds) in apartments, townhouses, and stacked townhouses that replaced aging, energy-inefficient single-story units. The range of housing types responds to challenging topography and fits into the surrounding neighborhood context.

While nearly 93 percent of New York State residential heating comes from fossil-fuel sources—mostly natural gas—Maplewood uses electric heating from heat pumps, with at least 50 percent of external power from regional solar farms. “Deploying heat pumps on this scale is unprecedented in this climate zone. It’s the largest collection of heat pumps within a single development in the Northeast,” said Max Zhang, fellow at Cornell’s Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future. The project is being monitored as a “living laboratory” to study non-fossil fuel heating on a large scale in Upstate New York. “The transition from traditional heating methods to heat pumps holds the promise of substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions,” notes Earth.org. Every Maplewood building is Energy Star certified.

The project provides a variety of open spaces, covering 4 acres out of 17. These include several neighborhood greens, hardscape plazas, community gardens, tot lots, and a trail adjacent to the site that leads to campus and a regional trail network. A stand of mature trees was preserved to deliver expansive views to the region’s natural beauty.

“A community garden was provided for local food production, and the entire site utilizes rain gardens and bioswales to responsibly hold and treat stormwater,” according to Brian Tomaino at Torti Gallas. Integrated stormwater approaches included pervious paving and filtration vaults in already-reduced parking areas, and careful preservation of existing slopes and trees. Anticipating the transition to electric vehicles, charging stations are provided in off-street parking spaces.

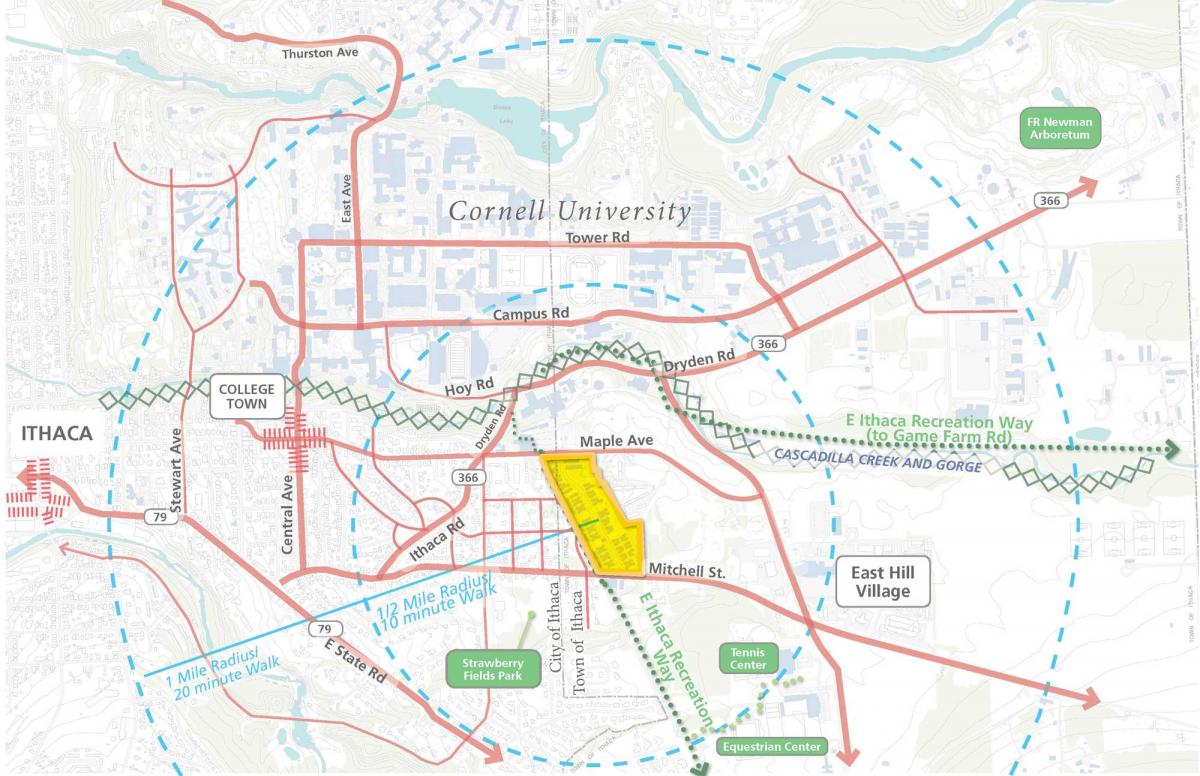

Maplewood employs the core components of neighborhood design that relate to climate adaptation and mitigation. Torti Gallas describes these as follows: Designing well-connected and complete streets that encourage multimodal transportation, especially walking, for daily activities reduces dependence on gasoline-powered cars and promotes healthy lifestyles. Articulated, human-scale architecture defines the street as a shared public realm. Entry stoops, covered porches, and balconies activate streets, while block sizes and street sections are pedestrian-oriented. Significantly reduced off-street parking requirements encourage alternative modes of transport while lessening heat islands. The project provides contextual connections to the surrounding neighborhood fabric.

The location is within walking distance of campus and substantial mixed-use. It is well-served by regional bus transit. While some grad student residents own cars, they don’t have to—they can easily get by without one in Maplewood, and that’s a benefit of urbanism relative to climate.

Overall, Maplewood demonstrates how urban plans can facilitate climate action in multiple ways. The core components of urbanism reduce the burning of fossil fuels for transportation. Urbanists are well practiced at bringing together multiple disciplines—in this case, green energy experts, builders, and landscape designers—to address the complex issues associated with carbon emissions and climate.

The project addresses community resilience in several ways. The vegetable gardens enable local food production. The ease with which somebody could live without a car in Maplewood will help residents in future times when energy costs rise. Walkability and connection to trails boost active living and health—surely a resilient community is one that invests in the health of residents.