Sacramento adopts progressive Missing Middle code

Sacramento’s new citywide Missing Middle Housing (MMH) ordinance is one of the most progressive and comprehensive in the US. Based on a study by Opticos Design, the interim ordinance applies to the city of 528,000 but adjusts the requirements and allowances according to what will work in individual neighborhoods and districts.

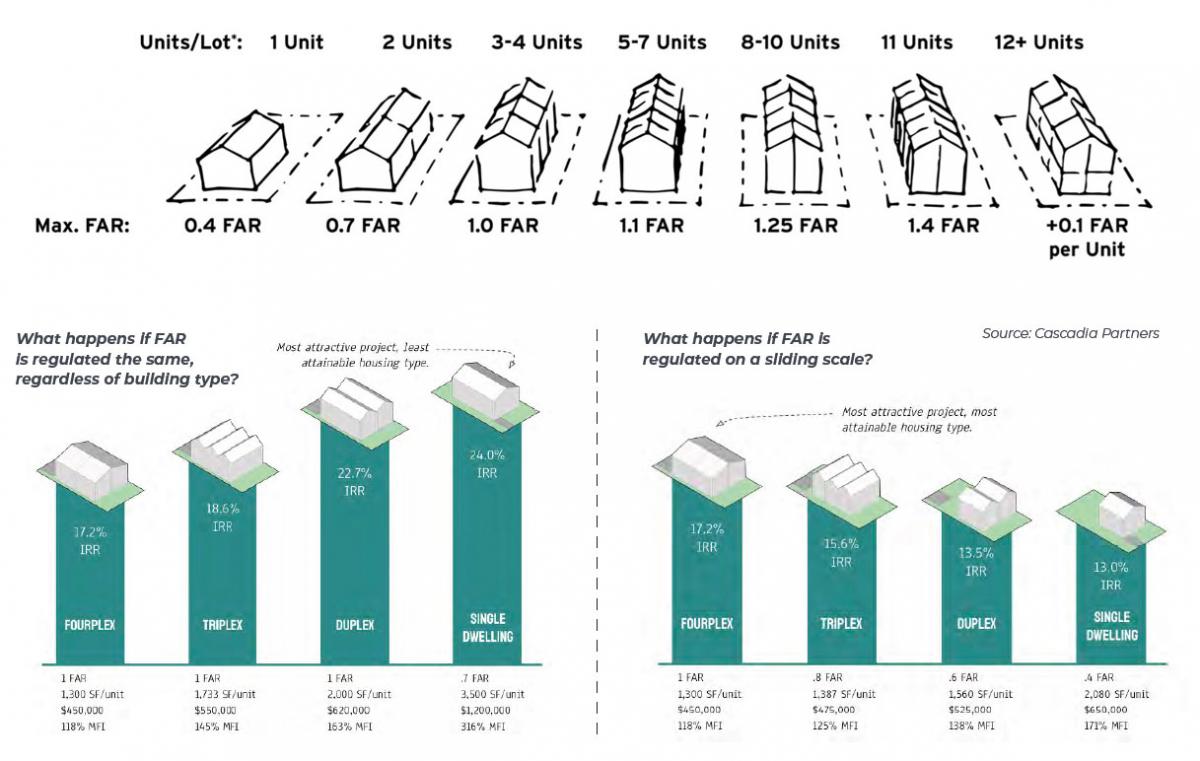

The Missing Middle Housing Study enables various scales of housing based on the context and proximity of transit and services. Development analyses were conducted to test the financial viability of building types and configurations in every city sector.

The ordinance goes beyond the typical missing middle reforms—which often allow 3-4 units on single-family lots—to enable four-plexes, six-plexes, eight-plexes, and ten-plexes, cottage courts, small homes on small lots, and other options, based on location. There are no density caps—only maximum floor-area ratio (FAR).

Key features include:

- A sliding scale FAR incentivizes more attainable housing types (like four-plexes) while discouraging large McMansions on small lots.

- An extensive lot size analysis across the entire city determines which lot sizes and widths are most common, to inform the catalog of Missing Middle housing types. “This is not an uncommon process, but the scale at which it was done is unusual,” says Dan Parolek of Opticos, who invented the term “Missing Middle.”

- Homeowners can build into the front setback in exchange for porches, trees, and other frontage improvements. This incentivizes the transformation of automobile-oriented streetscapes. Many residential neighborhoods have 20-foot setbacks; the ordinance reduces them to 10-15 feet if streetscape benefits are provided. “We wanted to demonstrate how much better it works to push parking to the rear … in these more suburban conditions,” Parolek explains.

- Extensive 3D test fits illustrate likely build-out scenarios to inform the pro forma analyses.

- Developers get additional square footage for deed-restricted affordable units based on a Local Bonus Program.

- A Displacement Risk Assessment was conducted “to ensure that policies and changes do not push vulnerable and historically marginalized black and brown households out of their neighborhoods,” Parolek explains.

According to Mitali Ganguly, an associate with Opticos, the study and ordinance were adopted with substantial public support and no community opposition.

The sliding scale for FAR is based on the approach taken by Portland, Oregon. Without the sliding scale, the most profitable development of a lot would be a large single-family house. With the sliding scale, a more affordable four-plex is the most profitable. “We call this the Missing Middle sweet spot of feasibility, attainability, and livability,” says Parolek. He explains that Portland standards have been in place for four years, and the track record of Missing Middle development in that city convinced Sacramento officials to employ the same strategy. The same financial analysts, Cascadia, look at both cities.

The law also incentivizes planting shade trees to further the City’s climate goals.

With these changes, Sacramento became the first city in California to allow multiunit housing in all single-family neighborhoods, according to the Sacramento City Express. The practical feasibility work done before the ordinance adoption may ensure that the changes will have a real impact.

“We have many residents, young and old, who want to stay in their community but can’t afford to. Without more affordable options, they are being forced to move,” Associate Planner Nguyen Nguyen to the City Express. “Through three years of collective effort and collaboration with our engaged residents, the Sacramento community has delivered a promising solution in response to this challenge, and I’m grateful to have been a part of that process.”