A model and microcosm for housing solutions

Kalamazoo is a microcosm of a nationwide housing problem, The New York Times writes, explaining that Michigan is a “mitten-shaped miniature of what the entire country has gone through,” and the City is representative of the state.

According to Zillow, the median home value in Kalamazoo and surrounding areas is $233,750. The price has nearly doubled in seven years despite a stagnant population, Zillow estimates.

“The housing crisis has moved from blue states to red states, and large metro areas to rural towns. In a time of extreme polarization, the too-high cost of housing and its attendant social problems are among the few things Americans truly share,” writes Conor Dougherty of the Times.

According to economists, Michigan is building only about 15,000 new homes annually, far short of the 25,000-30,000 needed to keep up with the replacement of aging housing stock and changing demographics. In the Kalamazoo market, construction plunged after 2006 and has yet to recover. That aligns with what is happening throughout the US, which is short at least 3 million housing units (some estimates are as high as 4.5 million). Since the housing crash 16 years ago, the nation has been under-building housing.

For many years, this problem was masked by recovering housing prices, followed by affordability issues in hot markets only. In this decade, the rising prices have spread far and wide, with the biggest jump between 2020 and 2022.

Even before the 2008 housing crash, the US housing market was changing, but the zoning codes and infrastructure that support real estate were not responding rapidly enough. During the 2010s, the housing market mostly grew in single-person households, yet zoning and thoroughfare investments still largely supported single-family housing in sprawl—a model geared toward 20th-Century demographics. We need more diverse housing in walkable neighborhoods.

In that way, Kalamazoo may be a model and a microcosm. The City of 73,000 addresses the mismatch between regulations, investments, and housing with a four-part strategy that includes:

- Zoning reform

- Missing middle housing

- Pre-approved building plans

- Financial support and incentives

Zoning reform

The City began reforming its zoning in 2018 after it surveyed lots and found that most did not conform to current zoning. For example, a typical city lot is 33 feet wide, while the zoning required 60 feet. That rule and others made infill development difficult, including creating barriers for homeowners to secure financing for rehabilitation.

One dramatic example of how zoning reduced the housing supply in the city involved the creation of a land bank of poorly maintained houses in 2010. The city acquired more than 260 properties and had federal dollars for construction. Two-thirds of these properties were nonconforming—so they were demolished rather than rehabbed. “It’s heartbreaking to think of what they did rather than fix the zoning. Could have used the federal dollars to rehabilitate the homes at the time,” says Rebekah Kik, Assistant City Manager.

Also, codes mandated single-family housing throughout most of the City. That policy limited density and housing choices, and the City sought to change the one-house, one-lot formula.

The zoning reform is ongoing because Kalamazoo has to go neighborhood by neighborhood, getting input on what residents want for each part of the City. Zoning reform started with high-intensity commercial areas, allowing more residential units to be built. However, the city has also relieved housing pressure by allowing up to two accessory dwellings per lot. In some cases, the city is allowing multiple buildings per lot. The goal is for regulations that open up the housing supply, cut time and cost for construction, and remove barriers to development.

Missing middle housing

Despite some vacant land, the need for new housing is greater than what can be built on land-bank lots—if only one house is built per lot. Therefore, Kalamazoo creates opportunities for by-right development of missing middle housing on the available land. These include duplex, triplex, four-plex, townhouses, and small apartment buildings. The city’s first cottage court is under construction.

These “missing” housing types contribute to affordability because they reduce land costs. But they are also about meeting the needs of diverse households today.

The “sweet spot” is 4-12 units, and the city is working to create prototypes.

“The goal is to bring back that gentle density that an urban city requires for affordability and to meet needs,” Christina Anderson, City Planner/Deputy Director, Community Planning and Economic Development.

Pre-approved building plans

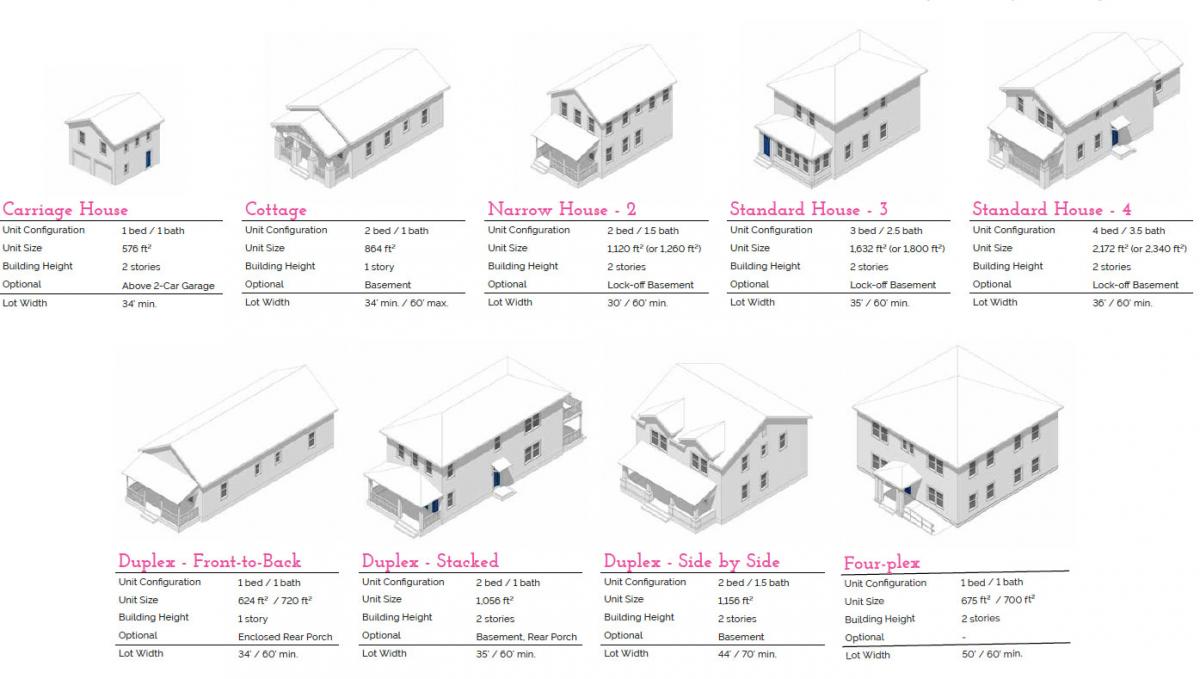

After witnessing the success of pre-approved building plans in nearby South Bend, Indiana, Kalamazoo worked with architects Jennifer Griffin of J. Griffin Design and Jennifer Settle of Opticos Design on plans based on the architecture of traditional city neighborhoods. The designers created plans for eight different types of housing designed to meet all local codes and fit on common-width city lots.

The goal is to make entitlement quicker, more predictable, and less costly. However, implementing this system presents hurdles. For example, local builders need more experience with traditional urban housing types. Also, some infill neighborhoods had not seen new housing for decades—often because home values would not cover the construction cost and profit. Builders had to be sold on economic viability.

So, the city funded a “proof of concept” with a local nonprofit, Kalamazoo Neighborhood Housing Services (KNHS). A duplex with two 1,000-square-foot units and a rear yard ADU was completed in 2022. This three-unit type allows a household to live in one home and rent two units for income. The project taught the city important lessons to improve the program and make it more attractive to builders.

“Among the worst surprises was to learn that there was an $18,000 charge from the water department to connect the water line based on how the house was situated. This issue was fixed for future builds … an example of why the city needed to be so hands-on to bring this idea to market,” Strong Towns reported.

This example points out how cities can benefit from a pre-approved housing plan program beyond the houses built within it. These programs force departments to work together to uncover hidden regulatory burdens and promote efficiency.

KNHS went on to build more houses using pre-approved plans. As of 2024, 48 homes have been built using pre-approved plans. The houses fit comfortably into old neighborhoods, employing simple shapes with inexpensive foundations, roofing, siding, detailing, and utilities. The all-electric power heat is cheap because the units are well-insulated—an improvement over drafty old houses. The plans have been made available to for-profit developers.

Financial support and incentives

Building momentum for new housing in the City requires surmounting many barriers, which require policy and program responses that go well beyond zoning and entitlement. These include:

- Funding and support for contractor training. In 2020, the City saw a need for emerging developers and a shortage of trained workers and minority contractors. The City sponsored a “small developer boot camp” with the Incremental Development Alliance.

- Predevelopment and technical assistance. The City partners with a community development financial institution to help with small developers' pre-development costs. This may include due diligence on land, which may cost $15,000-$30,000, an expense many emerging developers can’t cover.

- Tax to support affordable housing developments. The City recently approved payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) for a 228-unit affordable housing development not far from downtown. The project, when built, will provide 81 percent of units at 60 percent of the area median income (AMI) in exchange for 5 percent of rent going to the city for 45 years. This city tax support will enable the developer to apply to the Michigan State Housing Development Authority for funding. MSHDA runs the low-income housing tax credit program.

- Reduced land price based on affordability. Builders purchasing from the City land bank get up to a 75 percent reduced price based on affordable housing units provided.

- Maintenance support. Maintaining the historic housing stock is just as important as building new units, and the city has programs for emergency home repairs, senior citizen home repairs, roof repairs, rehabilitation for Housing Choice Voucher holders, and more.

Kalamazoo has one unusual advantage over similar cities. The Kalamazoo Foundation for Excellence (FFE) was set up a few years back, endowed with nearly a half billion dollars by wealthy businessmen to directly support programs related to the City’s strategic vision, Imagine Kalamazoo 2025. Among other things, FFE subsidizes city tax rates to bring its millage down below suburban municipalities (like many cities, Kalamazoo has a higher rate than surrounding communities). FFE funds many programs that directly or indirectly deal with housing.

There are signs that Kalamazoo’s efforts are beginning to have an impact. In 2023, housing permits for the county topped 700, the highest level in six years and the third highest since 2007.

Kalamazoo employs multiple strategies to respond to the real estate market, paying attention to affordability and housing types that fit into neighborhoods. “We are not just telling people, ‘here’s how you set the table;’ we are setting the table. We are taking city resources and using them for real dollar investment,” says Anderson.