From expressway to parkway

At the same time that New York State is looking at burying a freeway in Buffalo, the state DOT is also studying a plan to replace the 3.5-mile-long Scajaquada Expressway with a parkway and boulevard.

Since the 1950s, the Scajaquada Expressway in Buffalo has divided a Frederick Law Olmsted-designed park and greenway, hampering neighborhood mobility. Of all “Freeways Without Futures” proposals, Scajaquada is unique: It would create a multiway boulevard section through a neighborhood and a parkway in a historic green space. The Greater Buffalo Niagara Regional Transportation Council (GBNRTC) plan for Reimagining the Scajaquada Corridor is located in the transportation council’s Region Central, between downtown neighborhoods and North Buffalo.

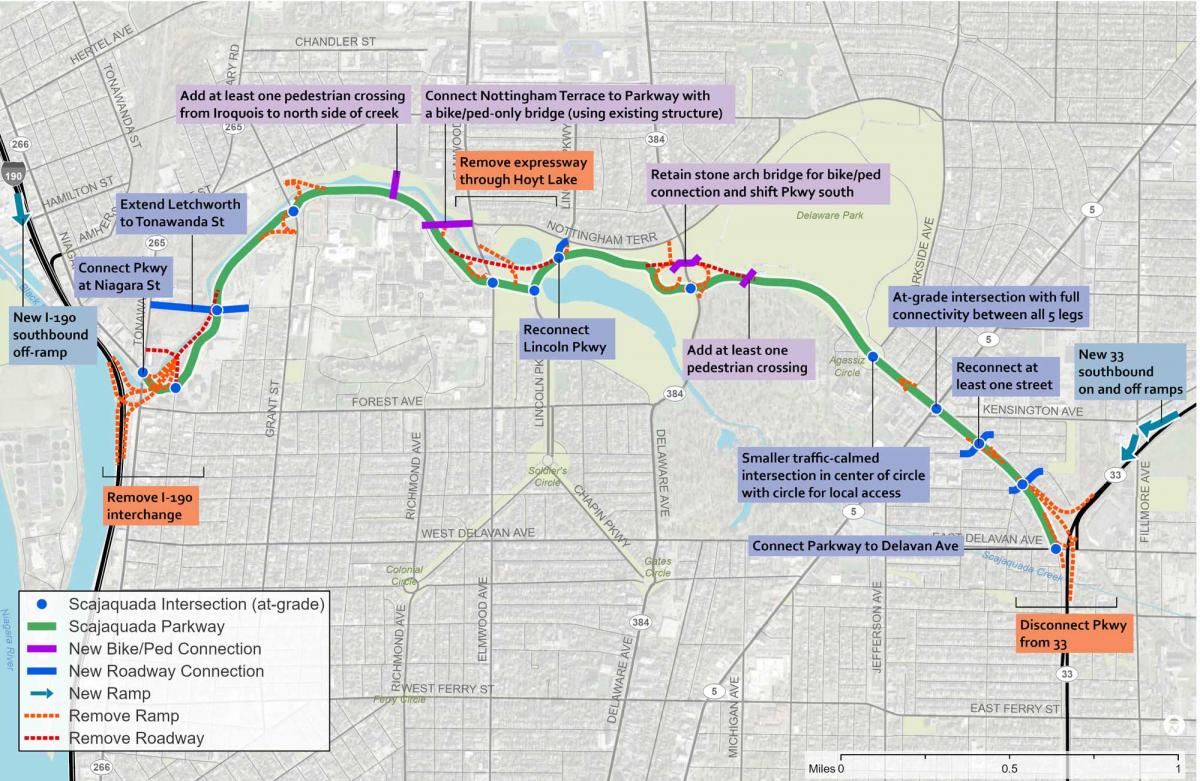

In May, Gov. Kathy Hochul announced that the state would study the plan and assess the traffic and environmental impacts. “The expanded study, expected to be completed in 2027, will also incorporate the GBNRTC’s proposals for reimagining the Scajaquada Expressway, which include transforming it into a two-lane, at-grade roadway with enhanced green spaces,” notes the New York Construction Report. If all goes well, the 3.5-mile-long corridor could be transformed by 2033.

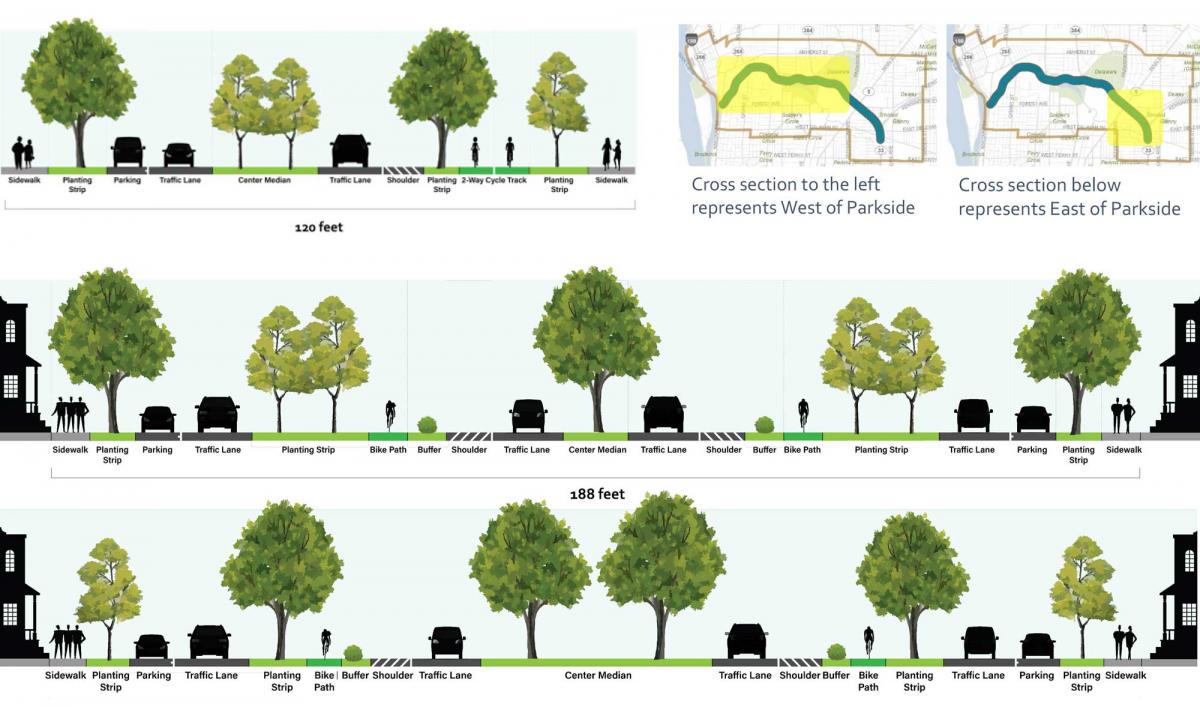

The GBNRTC worked with the consulting firm Stantec on a plan that broke through political gridlock that had hampered progress since 2005, when the City began to look at Scajaquada’s future. The plan calls for reducing the travel lanes from four to two in addition to drastically changing the character of the roadway. The 0.75-mile-long boulevard section will also have two slow-moving local lanes on the side to accompany faster-moving central through lanes. Up to seven rows of trees will help recreate a historic parkway on the route from the first half of the 20th Century. There would be more green than asphalt, and room for bicycle infrastructure and sidewalks in front of the existing houses.

The longer parkway section would have a narrower right-of-way, with a central median, cycle tracks, and sidewalks. Plans include enhancing intersections throughout the corridor, and upgrading 13 miles of connecting roadways, integrating two mobility hubs, and more.

Stantec reported to CNU that a coalition was built on three strategies:

- Focus on place. Reframe planning from a regional to local focus by declaring the urban neighborhoods directly impacted by the Expressway as a place in their own right—Region Central, a district with shared interests, needs, and aspirations whose leadership formed a coalition that gained a prime seat the planning table.

- Use data. Remove threshold barriers that overwhelmed support for removing the Expressway by arming the coalition with data demonstrating that fears of Carmageddon were unfounded and few suburbanites still relied on the Expressway to access Downtown

- Inspire a diverse coalition. Create a broadly shared vision using a series of lenses beyond transportation—e.g. Main Steets, health, equity, recreation, cultural heritage, environmental quality, neighborhood cohesion, Olmsted Legacy, and mobility—that enabled advocates for each lens to collaborate in crafting a shared vision co-created by diverse members of the public and coalition.

According to Stantec, the data that made the difference included:

- Almost two-thirds of all driving trips originating in Region Central are less than 5 miles in length. Since 2016, vehicle volumes are the lowest in two decades.

- Only 18 percent of all trips on the Expressway are work-related

- Less than 20 percent (19 percent eastbound, 8 percent westbound) use the full expressway as a regional connector; and most critically;

- In each Region Central neighborhood, almost all walking trips (95 percent) – do NOT cross the Expressway, demonstrating how it acts as a barrier.

Like many obsolete freeways, the Scajaquada was proposed to help save downtown but ended up harming urban life. The expressway mostly benefitted suburban residents, and those benefits were short-lived. The expressway follows the path of Scajaquada Creek, which goes through the Olmsted-designed park and a cemetery.

Along with the expressway transformation, the creek “will be restored with local green-space and natural habitats and re-visioned as a waterfront landmark. The improved bike and pedestrian pathway will provide direct access to the [Buffalo River] waterfront.”

Buffalo Rising reports that the GBNRTC “rescued the issue of the Scajaquada Expressway from 20 years of stagnation under NYSDOT‘s insular, myopic domain. Furthermore, they have approached the undertaking in an exemplary fashion that hopefully will become a model for the future handling of similar important projects in the City of Buffalo.”