How walkable places lead to healthier people

Twenty years ago, Urban Sprawl and Public Health was published, marking a watershed in our understanding of how the built environment impacts human well-being. The book by Jackson, Frank, and Frumkin explained the science of how walkable places are better for your health than living in sprawl—and in the last two decades, the evidence has only grown stronger.

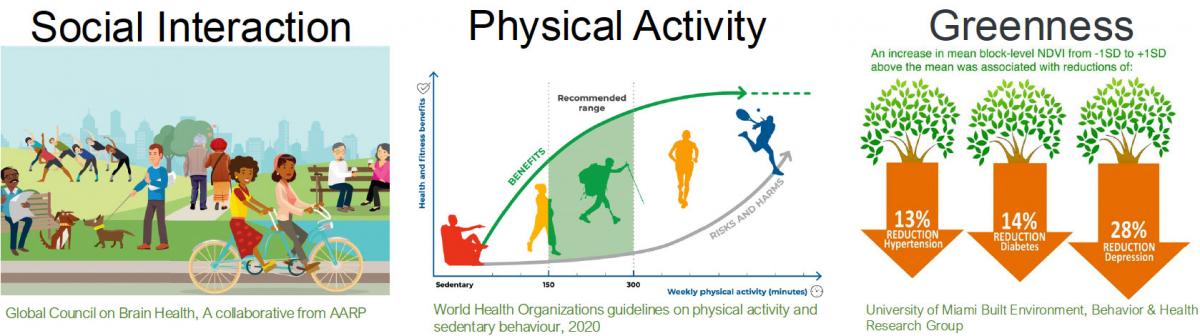

University of Miami architecture professor Joanna Lombard and urban planner Jeff Speck outlined this research on CNU’s On the Park Bench. Lombard, who has studied this topic with the UM Built Environment Behavior & Health Research Group, describes three primary factors:

- Greater levels of social interaction are strongly associated with higher likelihood of survival. These findings remain consistent across culture, age, sex, initial health status, and cause of death.

- Physical activity decreases risks of heart disease, premature death, muscle wasting, 13 types of cancer, hypertension, type II diabetes, stroke, and depressive symptoms and increases aerobic capacity, muscle strength, and mobility.

- Higher greenness levels are associated with reductions of multiple disease outcomes including depression, dementia, stroke as well as benefits to cognition and well-being.

Walkable neighborhoods with buildings that relate to the street, destinations within walking distance, and good tree canopies and green spaces demonstrate all these virtues.

Social interaction has been studied for 60 years and consistently correlates with better health. Especially important are “weak ties,” informal connections between neighbors who wave and say hello, contributing to mental health and outlook. “Elders who lived in blocks with few positive front entrance features were 2.7 times more likely to have poor physical and mental functioning, compared to elders residing on blocks with greater numbers of positive front-entrance qualities,” according to University of Miami research.

The UM research is not based on census blocks—like most health research—but urban blocks that correlate better to the physical characteristics of neighborhoods. That is how they determined that “a child living in a residential block was 1.74 times more likely to have conduct grades in the lowest 10 percent than a child living in mixed-use blocks.” Children with low conduct grades are associated with greater negative outcomes later in life.

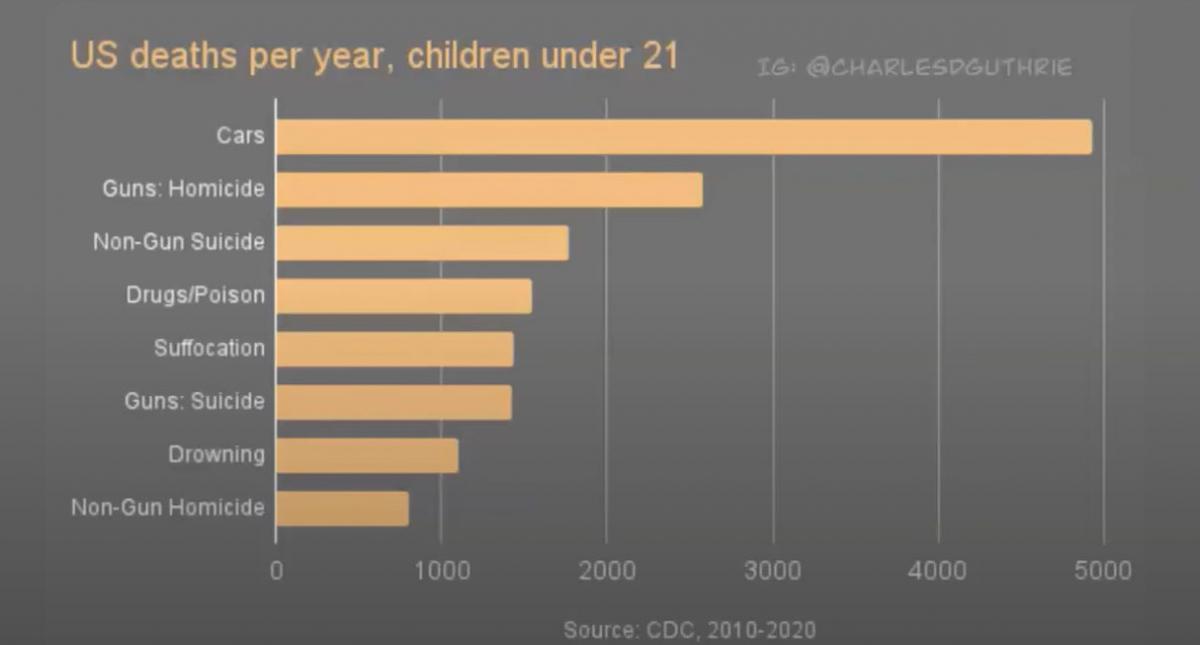

Speck, the author of Walkable City and Walkable City Rules, focused on an important health-related statistic that differs between walkable cities and sprawl: automobile crashes. This is by far the leading cause of death for children under 21, Speck shows—double the next cause, which is shootings and guns.

If you compare a walkable city like New York City with sprawl, the difference in automobile-related deaths (including pedestrians hit by cars) is astonishing. While New York City loses 3.9 people per 100,000 annually to automobile crashes, Hillsboro County, Florida, (a sprawling suburb of Tampa), experiences 67.5 per 100,000. “If you isolate the suburban environment, it is literally almost 20 times as bad as our more walkable places,” Speck says.

The greatest risk is to children, people who are economically challenged, and minorities. The injuries from automobile accidents, even more than the deaths, contribute to the nation’s health bills. “A lot of hospitals find that half of their business, if we can call it that, is car crash business,” Speck says.

The “suburbanization of poverty” is a big factor. Entire landscapes in the suburbs were designed with nary a thought for pedestrians. There are no sidewalks, the roads are inhospitable, and the distances are great. Planners assumed that everyone would drive, and yet, increasingly, people who live in the suburbs have to walk. “You see people crossing (these big arterials) as pedestrians,” Speck says. “This auto-zone has become the only affordable place for a lot of Americans.”

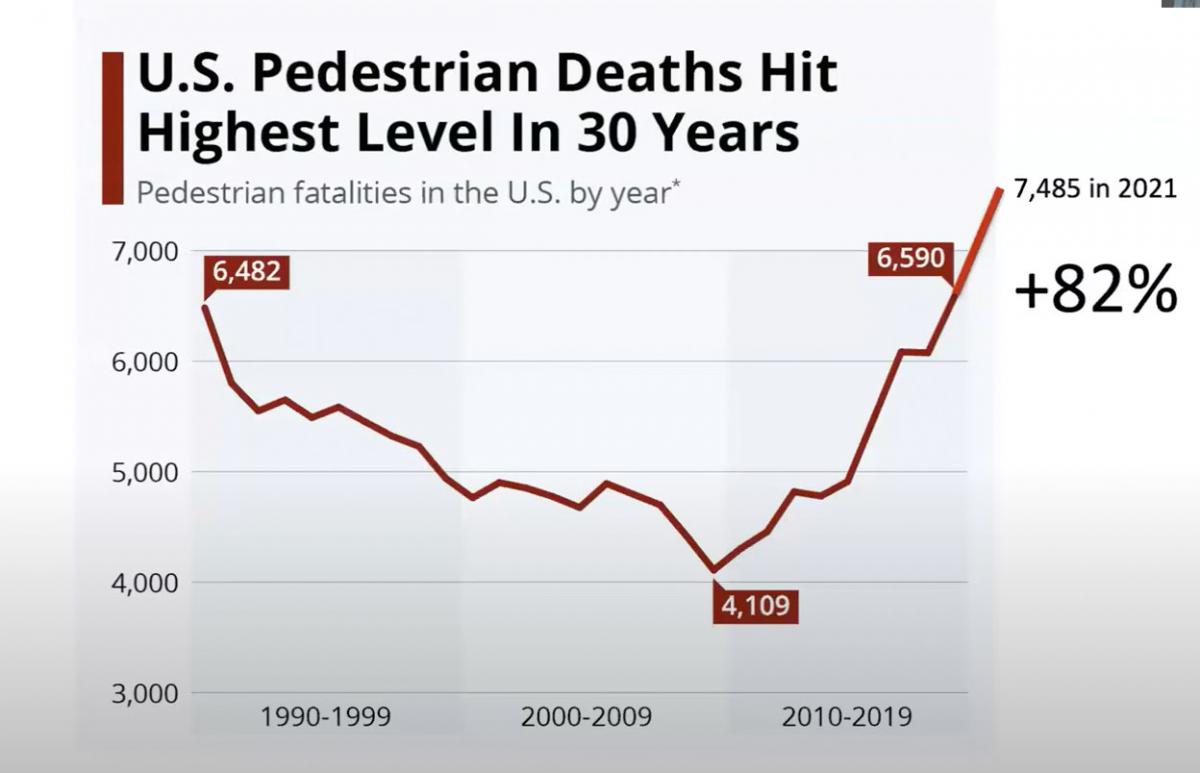

In the US, automobile deaths have risen in the last decade and a half for one reason—pedestrian deaths have soared by 82 percent. Some factors, such as the rise in cell phone use by drivers and more SUVs on the road (more deadly than sedans due to hood height), are out of the control of urban planners.

But the most important factor to pedestrian deaths is the speed of the automobile, Speck says—and that is something planners can influence. We need to design streets to slow traffic. What he calls a “walkability study” is the best tool to make changes, he says. That results in a plan to do things like: Remove unnecessary travel lanes, narrow overly wide lanes, build bicycle lanes, revert one-way to two-way streets, replace signals with stop signs when possible, tighten oversized intersections, plant street trees, and more.

Places that lead to all of these better health outcomes can be built using the Charter of the New Urbanism, and the Canons of Sustainable Architecture and Urbanism, two CNU foundational documents, says Lombard. “All of these principles are in the DNA of the Charter and the Canons,” she says.

See the entire video: