Voters choose transit in two sprawling cities

In the excitement and consternation of the national election in November, it was easy to miss some good news at the ballot box in a pair of America’s fastest-growing big cities. Citizens in the Nashville and Columbus regions voted by healthy margins to tax themselves to invest in transportation improvements that have the potential to make two of the most auto-dominant urban areas in the United States much easier to navigate without a car.

The firm I lead with longtime CNUer Jeff Speck, Speck Dempsey, is active in both places and encouraged by what we hear from local leaders and community stakeholders. In Nashville, first-term Mayor Freddie O’Connell may be one of the most pro-transit mayors in the country and Vice-Mayor and Council President Angie Henderson is a prominent and committed urbanist. In Columbus, local leaders such as Mayor Laurie Jadwin of Gahanna, Ohio, understand the need to get the region to plan for people moving by bus, bike, and foot, and, in the wake of the win at the ballot box, the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission and Central Ohio Transit Authority are coordinating plans to bring bus-rapid transit to the region for the first time.

Let’s start in Music City, where Mayor O’Connell is leading the way. A former Board President at Walk Bike Nashville, the grassroots advocacy organization, former Chair of Nashville’s Metropolitan Transit Authority, and more recently a district City Councilmember, Freddie put his political weight behind the ballot initiative and helped carry it over the finish line. A week after the vote, Mayor O’Connell told Jeff Speck, “This is a game-changer for Nashville.”

To be sure, Nashville has a long way to go. Data firm Replica estimates that Nashvillians drive, on average, more than 40 miles per day, the third worst of the 50 largest metropolitan statistical areas in the country. Forbes magazine named Nashville “the city with the toughest commute.” Nashville’s transit agency, WeGo, is well run, but hasn’t historically had the resources or reach to draw many commuters. According to respected think thank, ThinkTennessee, San Diego, Denver, and Baltimore have roughly 50 percent more population than Nashville, but their transit ridership is 600-800 percent higher than Nashville’s.

Despite difficult auto commutes and limited alternatives, in 2018 the region’s voters rejected an ambitious ballot initiative that would have increased taxes to fund a $5.4 billion transit infrastructure plan, including a light-rail system, advanced bus-rapid transit, and downtown transit tunnel. That initiative lost almost two-to-one. As Jarret Walker has written, the plan’s project mix, “made it very expensive and at the same time very specialized. The concentrated investment in a few corridors would leave much of the city feeling left out…[it] didn’t connect the dots to how many Nashvilleans experienced their transportation problems, for example as traffic congestion or the danger to pedestrians.”

The smaller, less-geographically focused, more flexible proposal that passed this year was wisely tailored to win public support, and still represents a sea change for the metro area. Appropriately labeled, “Choose How You Move,” the initiative’s branding is not just focused on transit—it includes upgrades to pedestrian infrastructure and traffic signals, providing the hope of improving commutes for drivers, too. And of course, most transit trip starts with a walk or roll, so improving pedestrian infrastructure complements improvements to transit infrastructure.

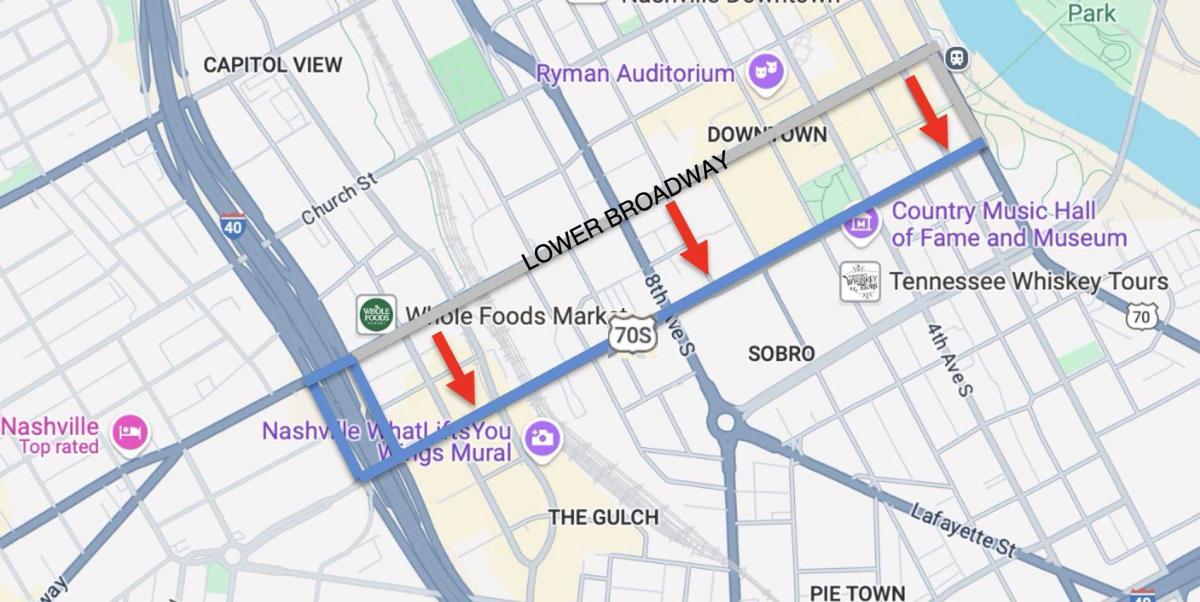

This time, voters flipped the script— turning the 2018 two-to-one defeat into a 2024 two-to-one victory, with 65.5 percent of voters supporting Choose How You Move. The $3.1 billion in expected revenue will fund the design and construction of 86 miles of sidewalk, 600 upgraded smart traffic signals, an improved bus system that will operate all day and night, a dozen community transit centers, and a score of park-and-ride facilities.

As the home of country music, Nashville has always held its place in the American consciousness, and its history has been shaped by transportation—it got its start as the terminus of the Natchez Trace, a trail developed by native people connecting the Mississippi and Cumberland Rivers. The city was an important port on the Cumberland and a vital railroad center in the 19th Century. In the early 20th Century the city had 50 miles of electric streetcars.

November’s referendum alone can’t restore that multi-modal glory, and we’re still likely to hear more country songs about pickup trucks than bus-rapid-transit, but it’s still a meaningful win and enormous opportunity for the region. The Metro government is already hiring an executive to oversee implementation of Choose How You Move, with a salary range that should attract national talent. Jeff Speck comments, “when people ask me about Nashville, I ask them to imagine what would happen if their own city’s most prominent walk/bike/ride advocate got elected mayor. That’s what we’re dealing with here.”

The story is similar in Columbus, which, like Nashville, is booming. From 2010 to 2020, the Columbus metro region saw its largest population growth ever, at 15.1 percent—faster than sunbelt cities Houston or Phoenix. During that decade, the region accounted for a staggering 90 percent of Ohio's overall population growth. The metro area is now home to 2.1 million people. Yet the city has no passenger rail service of any kind, and its bus service is underdeveloped and poorly connected.

This November, Franklin County voters approved a sales tax levy to fund a plan, called LinkUS, which dedicates resources to improving sidewalks, bike paths and trails, and bus service. But the signature component of the plan is a region-wide bus rapid transit system with five core lines that crisscross the county.

Approved by 57 percent of voters, it will ultimately lead to $8 billion of investment.

The first two BRT routes include a corridor on West Broad Street and another on East Main Street. Both would stretch from downtown to the edges of Franklin County. Future lines will connect Northwest from downtown and other lines that are still being planned.

Our firm has been on the ground in the Columbus area ahead of the vote. In late October, Speck Dempsey worked with the community of Gahanna, northeast of Columbus, to help them plan for BRT before it arrives. Gahanna is a bedroom community near John Glenn Columbus International Airport that has limited transit service today, and is a place where most people drive. The community, led by Mayor Jadwin, wants to be sure that any transit improvements deliver real benefits to residents, commuters, and the city’s tax base. Our work there, done in partnership with Able City East and Burgess & Niple, presents a vision for integrating BRT and Transit-Oriented Development concepts into a suburban context.

There’s tremendous uncertainty about what a second Trump term will mean for federal transportation policy. But at the local level, voters in Nashville, Columbus, and other communities sent a clear message that they value multi-modal transportation improvements and that transit, walking, and biking are essential components of a well-balanced city. Look for more wins like this in the years ahead.