Learning from Savannah

Last week CNU staff gathered in Savannah, Georgia, one of the greatest small cities in America. Among other things, this was an opportunity to learn about urbanism by walking and observing. In just three days, we saw much of the city and also nearby Beaufort, South Carolina, and Habersham—a new town inspired by the historic cities—and experienced the enduring benefits of great urban design.

The two biggest takeaways from Savannah are its sheer walkability and greenness, even in the winter (the same can be said for Beaufort and Habersham). Both qualities are not merely nice, but they are strongly linked to beneficial long-term health outcomes.

Short term, it feels like an easy place to enjoy historic buildings and the nature of the squares while racking up large step counts, according to Misty Adams, CNU’s Development Manager and newest team member. “There’s no stress involved. You come and stay and walk the entire city. It’s lovely. I wish more communities were like that,” she says. In other words, aerobic exercise that engages your mind through culture and architecture, with no stress. I averaged 14,000 steps a day; at home I have to work to get to 5,000. That’s what good urban design can do, and it is still true in 2025 after centuries of economic and technological changes.

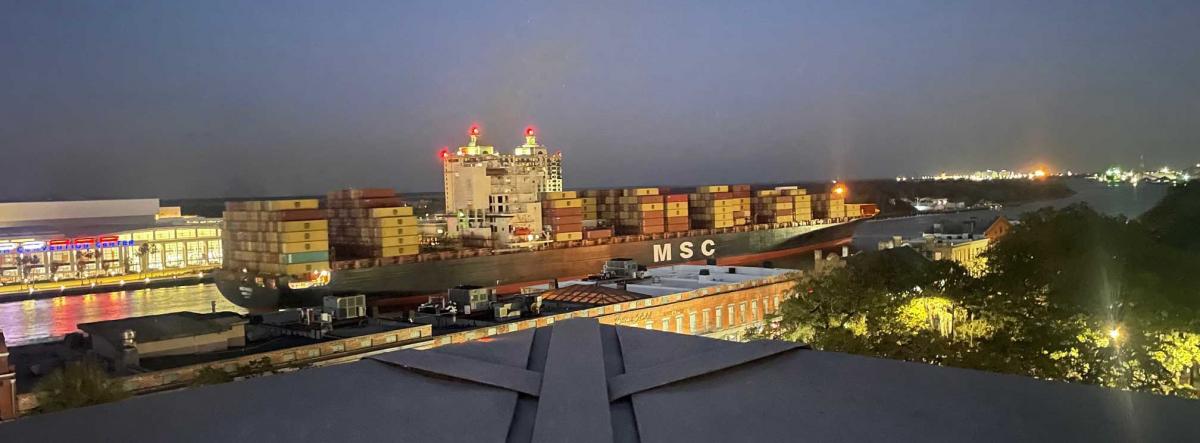

Savannah is not just some historical artifact; very touristy with nice restaurants and a setting for movies like Forrest Gump—the city was founded as a port nearly 300 years ago. It is now the second largest port on the East Coast, and I felt Savannah’s portness like no other city I had seen. From a rooftop bar, I was almost within shouting distance of a container ship going by.

Savannah appears to be a city much larger than it is, and that’s because downtown and adjacent neighborhoods have a powerful sense of place. Wikipedia says 147,000 people live in Savannah. With most cities of that size, you can walk through downtown in 10-15 minutes. In Savannah, you can walk for hours without getting bored.

The paradox is that, at the same time, downtown Savannah feels like a small town because there are few tall buildings and the traffic is surprisingly light around the squares. But the placemaking and historic architecture are in an elite category of cities like Charleston, Boston, New Orleans, and Philadelphia, which was drawn up by William Penn about 50 years prior to James Oglethorpe’s founding of Savannah. Philadelphia has a similar pattern of squares, but they are fewer and larger. One of Philly’s five squares now has the massive city hall, and I-676 and the Ben Franklin Bridge compromised two others.

One can imagine Oglethorpe looking at Philadelphia and saying, “nice plan, but what it needs is more squares.” Oglethorpe planned 22 squares, and all are intact and lovely. Savannah teaches us that you can never have too many squares. A parking garage was built on one in the 20th Century, but this structure was torn down, and Ellis Square was redesigned and landscaped in a CNU Charter Award-winning project. Walking in Savannah is rewarding because every few blocks, you come across another square shaded by massive live oaks. By and large, each square has a church and residences, and many feature commerce. This balance of uses was planned from the start and has served the city for three centuries.

Staff toured remarkable projects, especially Plant Riverside District, one of the most impressive adaptive reuse developments in America. Plant Riverside is the transformation of a former power plant on the Savannah River, and it won a Charter Award in 2021. Plant Riverside is only 4.5 acres, but at 670,000 square feet of mixed-use, every bit is put to good use. The district is designed with a series of small public spaces on the water, and it is a great spot for events or just hanging out. The power plant building is a hotel, and if you go, you have to check out the lobby, which doubles as a natural history museum. The smokestacks were preserved and lit up—they are beacons that can be seen for blocks. Savannah is a city of towers, but they consist of church steeples, civic buildings, or other small towers that would be overwhelmed in any city with skyscrapers. Savannah teaches me the power of small towers—you don’t have to crane your neck to see them—in a low-rise city. It’s not about the absolute height of towers—it’s about the contrast with the surrounding city fabric.

We saw a lot of great infill development, notably the residential development in Beaufort, which is seriously hard to distinguish from the historic fabric. We were reminded that through for-profit and nonprofit construction it is possible to build housing that enhances walkability and quality of the urban fabric with respectful and unassuming design.

Savannah was an early city to adopt urban tree canopy regulations, and the city’s trees are magnificent. The regulations will help to maintain that canopy and extend it throughout neighborhoods beyond the historic downtown. In summer, the squares are a respite from the heat and you can walk through downtown mostly in the shade.

Heading into downtown, the Uber driver warned me about one thing—take care on Savannah’s historic steps going down to the river. These stone steps are very steep and they don’t meet code. I imagine many a drunken tourist suffers a painful fall. But the steps point out that Savannah is on a bluff and protected from sea level rise, which is likely reassuring to residents.

Personally, I would warn visitors about the one-way streets. These appear easy to cross on foot because they are only two to three lanes wide. But cars speed, and you must be aware. The one-ways can take you by surprise, unlike the steps, which are immediately a little intimidating. On many other streets, like the main commercial thoroughfare, Savannah is a model of traffic calming.

Like many attractive, walkable cities, Savannah has gotten quite expensive. A one-bedroom goes for $1,700—but substantially more in the historic parts. That’s because places as beautiful and walkable as Savannah are rare these days. The city’s final lesson: We need to increase the supply of walkable urban places.