How urban designers came full circle

I have been reading a fascinating document—an AIA continuing education course that includes the most lucid history of urban design that I have read. The history is Unit 1 of a four-part course, Urban Design For Architects: Space, Place, And Urban Infrastructure, written by David Walters, professor emeritus of architecture at the University of North Carolina Charlotte.

The 6,000-word section—which CNU cofounder Andres Duany sent to me—explains why America’s cities look and function the way they do and why the New Urbanism emerged in the 1990s to challenge the planning and design status quo.

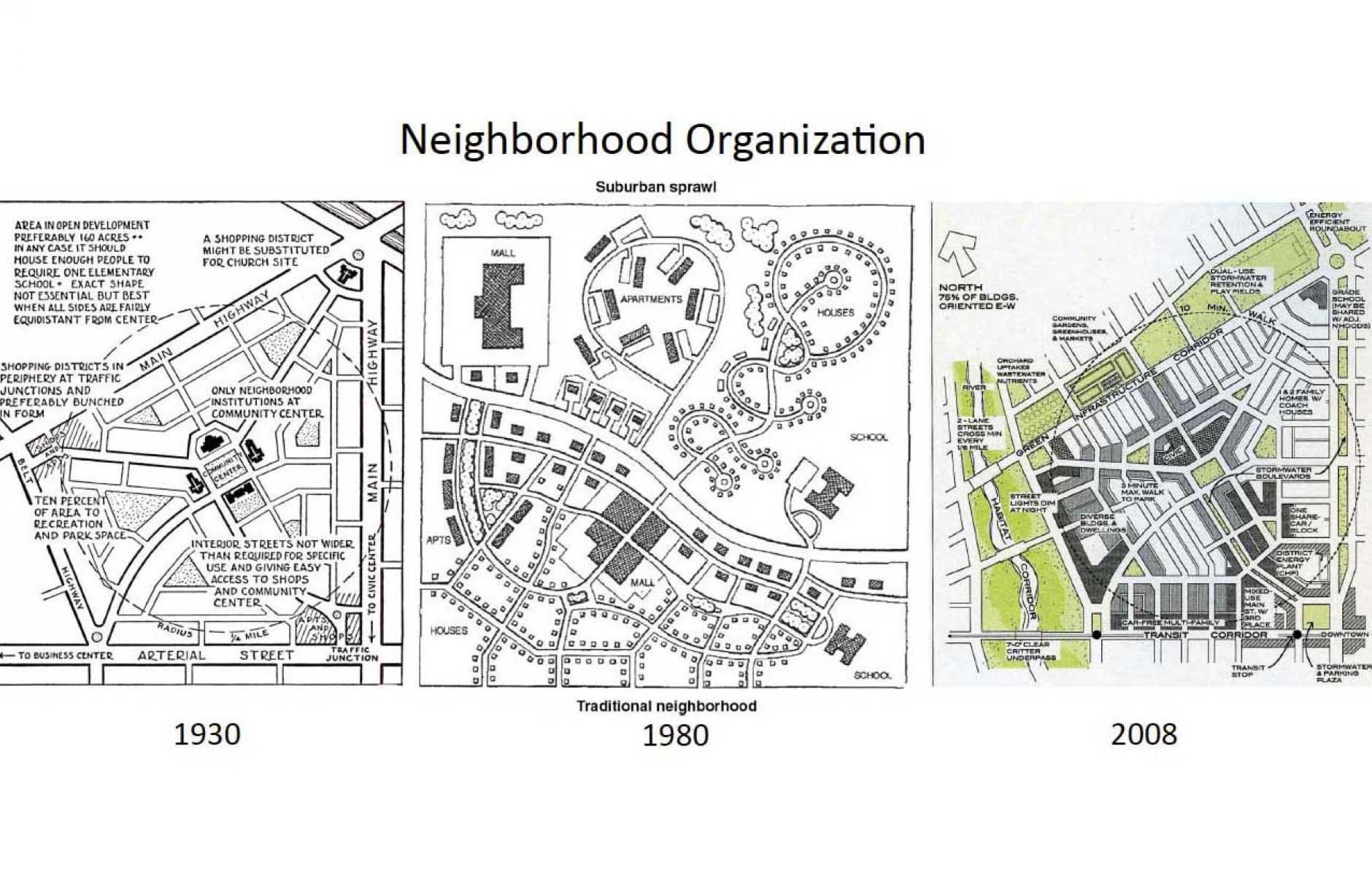

What makes the historical narrative confusing, Walters writes, is that the urban design profession started with walkable urbanism, renounced that approach in the second half of the last century, and now has come full circle, adapting traditional ideas to fit a modern context.

Urban design grew out of architecture and landscape architecture and originally promoted traditional neighborhoods like those associated with “streetcar suburbs,” walkable neighborhoods connected to turn-of-the-century transit. These ideas shaped American cities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But they were soundly rejected—even ridiculed—by urban theorists and practitioners during the “modern period” from the 1920s through the 1980s.

Radical modernist ideas were embedded in 20th Century zoning codes, real estate finance, and development practice to such a degree that most people forgot they were radical ideas and that alternative methods and techniques were possible. Modernist planning imposed a rigid separation of uses. To make a long story short, a cohort of architects became fed up, stopped believing what they were taught at schools, and launched the counter-movement New Urbanism in the 1990s.

“By the second decade of the 21st Century, urban designers have intentionally discarded those once-dominant modernist concepts and returned instead to a version of America’s traditional urbanism, updated to meet new concerns about sustainability and resilience.”

In summary, this sounds like a fairly standard story, told a hundred times in articles and books over the last two or three decades. But Walters’ history stands out in that it is comprehensive, concise, and extremely well-written. Many accounts tell part of the story. This is a one-stop shop without getting bloated. Urban design means “the art of making places for people,” Walters explains, and traces the history of modern practice to early 19th Century England, with ideas quickly copied and enhanced by American designers like Olmsted, culminating with a heyday of town planning in the early 20th Century.

“This pattern of urban design and planning remained mainstream American practice until the end of the 1920s. At that time much suburban development slowed due to the onset of the Great Depression, and development patterns began to change with the increase of individual car ownership and the consequent decline of public transit. No longer was it important to construct tightly organized, mixed-use and walkable communities. The private automobile allowed the elements of city life to be more widely spaced apart, but still quickly accessible by car.”

Walters explains how the Neighborhood Unit by Charles Perry and the Radburn by Clarence Stein, both in the late 1920s, represented a radical shift in planning—Perry’s model had more in common with traditional neighborhoods. A reaction against real city problems, including industrial pollution and over-crowded slums, led to zoning that went too far in separating all uses. Single-use zoning appealed to a 20th Century demand and push for efficiency. Socialist utopian ideas of the Bauhaus, in the CIAM Charter, were stripped of their political implications and fit into the American drive to efficiency like a hand in a glove.

“The urban ideas enshrined in the text became guiding principles and doctrine for many architects and planners involved in rebuilding British and European cities after World War Two. Moreover, these same ideas were transplanted into American practice in the late 1940s and 1950s by the many European architects, planners and intellectuals who fled fascism and persecution, starting new chapters of their professional lives in the USA,” Walters explains.

I have written and read much about this history, but I learned some things from this brief account. The rebellion against modern urban design began as early as the 1950s with a group of architects known as Team X, who “sought to enrich modernism with a sense of humanism and social reality that the simplistic Four Function model lacked. Through the 1970s and into the 1980s, architects sought ways to enrich and transform the overly simplistic concepts of modernist urbanism.”

Jane Jacobs made a powerful statement with her 1961 best-seller Death and Life of Great American Cities. And yet the urban design profession mostly rejected her arguments and Death and Life took 20 years to begin having an impact, despite becoming a standard text in the academy, he explains. The New Urbanism brought together multiple reform threads, including Traditional Neighborhood Development, Transit-Oriented Development, and inner-city infill work that emulated traditional urban form.

Joining together and writing a manifesto—the Charter of the New Urbanism—the New Urbanism received national attention in respected publications like Newsweek and The Atlantic in the mid-1990s, but the movement was still met with hostility on the part of major builders and financiers of the built environment, and the academy. But by the end of the first decade of the 2000s, most of the land-use professions were on board.

The above is a highly abbreviated summary of Unit 1. Unit 2 provides an overview of New Urbanism (NU), including the complete text of the Charter of the New Urbanism and an explanation of how to apply its design principles. The differences and similarities of NU and Landscape Urbanism, the other major urban design movement to emerge in the last 30 years, are also explained. Walters concludes that Landscape Urbanism is mostly compatible with New Urbanism, albeit with stylistic differences. Although Landscape Urbanism has been popular in the academy, Harvard in particular, it has been far less influential than NU in cities and real estate development.

Units 3 and 4 provide even more details on how to apply urban design principles—essentially New Urbanism—including strong explanations of the Rural-to-Urban Transect and Form-Based Codes. The continuing education course was created through PDH Academy, a leading online provider for practitioner continuing education. Here is the link to the course material, which I recommend reading, whether or not you take the course.

Walters tells me the course was written in 2019, but the material seems current to me today—probably because he takes a long view of history. He was asked by PDH to write this course, and he also produced one on Form-Based Codes.