Hurricane-ravaged city bounces back with new main street

Panama City, Florida, is well on its way to rebuilding from Category 5 Hurricane Michael, which swept away 95 percent of the tree canopy and damaged 90 percent of buildings downtown in 2018.

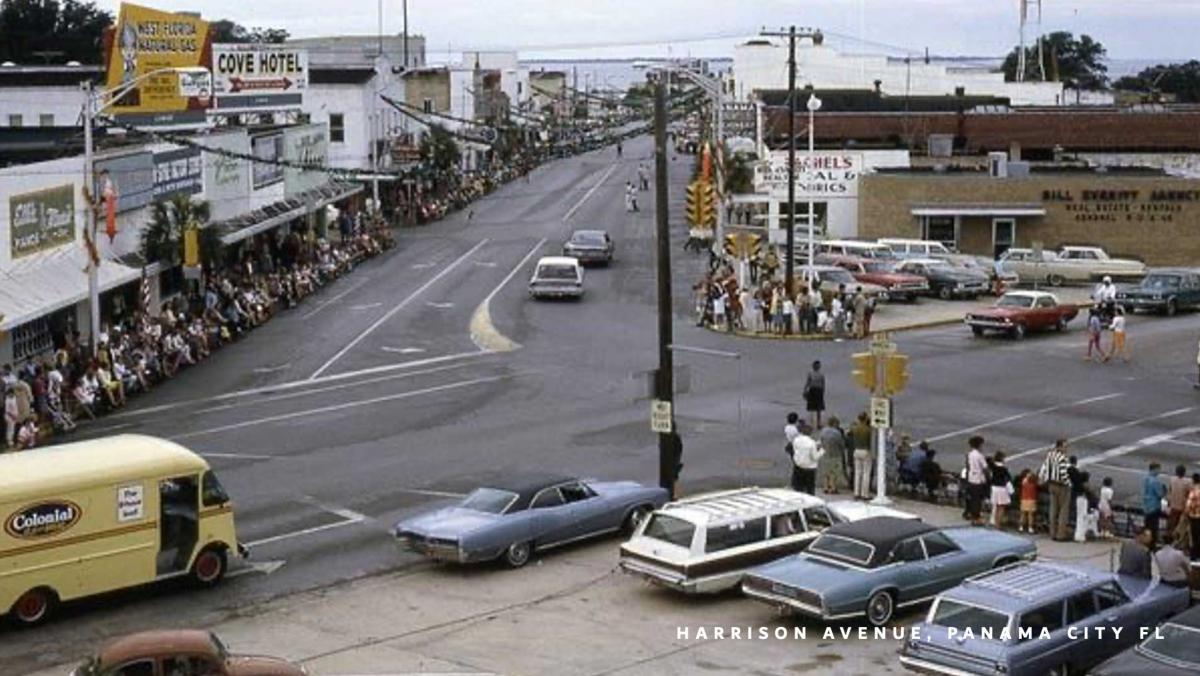

In 2020, the city and Dover Kohl & Partners won a Charter Award for the Strategic Vision for Panama City, a recovery plan that closely examined at sea level rise and risk from climate change. Revitalization of Harrison Avenue, the downtown’s primary street heart of the community, is a centerpiece of that plan.

The city completed phase 1 of a new Harrison Avenue streetscape a little over a year ago, and now phase 2 is underway. The city received a $6.9 million state grant to fund the improvements. Dover Kohl worked with transportation engineer Rick Hall on the street design, which included a circle and plaza at the primary intersection.

“There’s a growing collection of wedding photos on the circle on Harrison Avenue,” says Victor Dover. “No one was getting a wedding photo on the main street before.” The plaza is the central public space envisioned in the plan, and it has already become a symbol for the city on Instagram and the place where news reporters set up live-action shots, according to Amy Groves, principal at Dover Kohl. The traffic circle has a four-sided clock, damaged during the storm, that was previously in front of a bank for nearly a century. According to reports, the clock “nearly ended up in a junkyard.” The clock was restored and relocated in the intersection and has now become an icon of Panama City.

Harrison Avenue was historically the heart of Panama City, incorporated in 1906, but it lost some of its economic and social importance as the city sprawled to the north. Restoring downtown activity was a principle of the Strategic Vision—including strengthening place-based art and culture. Slowing traffic and making the street more walkable and bikable are intended to make downtown more attractive to residents and visitors. The design used shared-space techniques, including low curbs, widened sidewalks, paving bricks rather than asphalt, new trees and landscaping, and crosswalks with alternating-color pavers.

The city’s fast-moving planning process (approved one year after the hurricane) meant that recovery dollars could be used toward implementation. Almost as soon as the downtown and waterfront plan was completed, the city worked with Dover Kohl on a plan for historic adjacent neighborhoods. That process was affected by COVID-19, which meant that public participation was virtual. This second plan was completed in 2021.

Concepts of complete neighborhoods, great streets, and resilient open spaces informed both plans. The plan bravely mapped a sea level rise of up to 10 feet, calling for a waterfront promenade with the additional purpose of fortifying and protecting against a storm surge. A waterfront hotel has been built since that completed the first section of the promenade.

With an emphasis on trees and shading, Panama City implements a primary goal of urban design and climate change—ensuring shade for cooling and reducing urban heat islands. Street trees are associated with a 2-4 degrees F of cooling. They also promote walkability, leading to reduced obesity, cardiovascular disease, and mental health problems. Trees also retain rainwater. The reduced reliance on asphalt—replaced with wider sidewalks and planting zones of white pavement—likewise cuts heat retention.

Panama City has eliminated minimum parking requirements downtown, which is credited with spurring the reoccupation of historic buildings and constructing new ones. Less parking also means further reduced asphalt for water runoff and heat retention. Setbacks were changed in the zoning to enable facades to be constructed at the street right-of-way. The wider sidewalks have supported new restaurants and a proliferation of outdoor dining, Groves explains.

“The Harrison Avenue rebuild exceeded our expectations for the amount of activity and the level of helping the community come back,” she says. The plans also promote housing downtown in adjacent neighborhoods, particularly in the form of missing middle housing types. Panama City's comeback from a major storm in a way that boosts resilience and uses urbanist principles is an inspiration for urban designers addressing climate change and disasters.

This article was partly based on a presentation given by Amy Groves at CNU 32 in Cincinnati, Ohio, in a session called Fire and Flood: Restorative Urbanism and Climate Resiliency.