New towns are important part of New Urbanism

After two decades of city-focused urbanism, new towns are generating new interest. To answer the demand for new and affordable housing in developed countries in general and the US in particular, the thinking is that we need more than infill.

New Urbanism has long been associated in the popular imagination with new towns like Seaside and Celebration, sometimes called traditional neighborhood development (TND). New urbanists have often been disparaged for this work, partly because it envisions a better way of building on greenfield sites, which has been linked to suburban sprawl since the middle of the 20th Century. Also, some critics associate new main streets and walkable neighborhoods with stage sets. For many years, the top Google search for New Urbanism was titled “Why is New Urbanism so Gosh Darn Creepy?” about a TND in Colorado called South Main.

The movement has always been much broader than TND, as shown in the Charter and the Great Ideas of New Urbanism. Many new urbanists focus on infill, transit-oriented development, incremental development, suburban retrofit, highway transformation, and Tactical Urbanism.

Last week, I wrote a positive article about Daybreak in South Jordan, Utah, the largest TND in the US and probably the world, which is building its downtown. This resulted in a minor dust-up on a listserve of new urbanists, where Daybreak was referred to as “pragmatic compromise” and “enhanced sprawl.” Many in the New Urbanism are a little embarrassed by TND. The feeling is that if you are building a greenfield project, you are not trying hard enough. “That’s very nice, it’s better than sprawl, but why don’t you just build something downtown?” is the general response.

Daybreak and similar projects show why new towns and TND are vital—not just to New Urbanism but to the built and natural environments and human health. Daybreak arises from another important component of the movement, perhaps least understood, and that’s regional planning.

About 25 years ago, Congress for the New Urbanism cofounder Peter Calthorpe led a planning process called Envision Utah. The Salt Lake City metro area was, and is, growing rapidly. Envision Utah was sponsored by a coalition of civic, business, and political leaders. Participants were given the choice of business-as-usual development, which would have resulted in 409 square miles of sprawl connected by highways. Instead, they chose compact development connected by light rail and roads. That option would use up only 126 square miles of new land in a given period.

Although Envision Utah had no direct power, it had influence. The region has since built 45 miles of light rail with 51 stations, and jurisdictions have planned and implemented walkable mixed-use like Daybreak along the transit. Daybreak does not fit everyone’s ideal of urbanism—it includes a lot of single-family housing. And yet, it is quite walkable and bikeable. The site, which used to be a copper, gold, and silver mine, is a little more than six square miles. That’s the same size as Ithaca, New York, a historic, walkable city where I recently lived and raised a family. Ithaca and Daybreak have approximately the same population—about 30,000 people—but Daybreak is still growing and is projected to reach 40,000 or 50,000 people.

Daybreak is laid out in a connected network of streets, which is the case with any new urban town. The alternative to Daybreak is not putting everybody in downtown Salt Lake City. The alternative is lower-density sprawl, which has a dendritic, or tree-like, pattern of local streets branching off arterials. Just imagine if Daybreak were the density of sprawl, which is generally at about 2,000 people per square mile. Housing the same number of people would take up 20-25 square miles, and none would be walkable. That would be the business-as-usual scenario wisely rejected by participants in Envision Utah.

This is not just a matter of how much land is consumed. In the last 20 years, a large body of research has confirmed the benefits of walkability and active transportation in human health and physical, mental, and social well-being. For example, Diversity in commuting mode share (more walking, biking, transit use) has a positive relationship with better health behaviors, more leisure quality, more access to exercise, less sedentary living and obesity, and indicators of longevity, according to an analysis of 148 cities. Or, A fully gridded, compact street network would expect a 15 percent reduction in obesity rates, a 10 percent reduction in high blood pressure rates, and a 6 percent reduction in heart disease rates, as compared to the standard suburban network with its associated design characteristics, according to a study of California cities. Dozens of similar studies show that people, including vulnerable populations like children and the elderly, do better in walkable places.

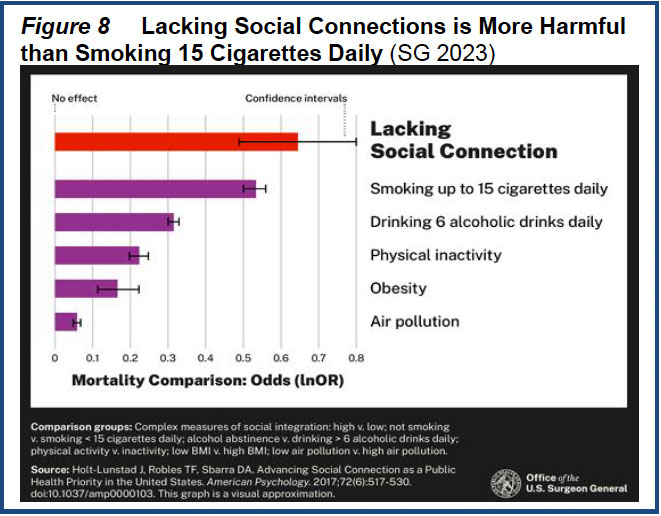

People socialize more in walkable places. They tend to have more friendly interactions on household trips, which contributes to mental health. According to the Surgeon General in 2023, lack of social connection is a huge health problem.

Part of the confusion may lie in defining sprawl, which is not simply greenfield development. Sprawl is a pattern, widely adopted in the middle of the 20th Century, that separates uses and housing types into distinct development pods, which are spread across the landscape at a distance that is not easily traveled by foot. Pods are linked by thoroughfares that allow for fairly high-speed travel. Sprawl was never meant for walking—it was set up for car travel. Walkable neighborhoods, by contrast, accommodate automobiles but don’t privilege them. More attention is given to walking, biking, and other forms of getting around.

TND is described in the preamble of the Charter of the New Urbanism: “We stand for the restoration of existing urban centers and towns within coherent metropolitan regions, the reconfiguration of sprawling suburbs into communities of real neighborhoods and diverse districts, the conservation of natural environments, and the preservation of our built legacy.”

As this paragraph indicates, restoring existing urban centers and towns is the priority, but we can’t reform the built environment without building a better alternative to sprawl. Even if we revitalized every historic neighborhood, we would continue to build sprawl outward without a better form of greenfield development. Walkable neighborhoods are expensive, partly because they are undersupplied. To meet market demand, we need infill plus well-planned new settlements.

Projects like Daybreak improve the lives of the people who live in them. New urbanists should be proud of that work, especially when a city-wide or regional plan supports such development. If folks want to build new towns, new urbanists have the expertise—applying it widely would do a lot of good.