For housing, the medium is the street

There’s a new book generating discussion on housing and zoning—two topics that urbanists have been immersed in for decades. Abundance, by prominent progressive thinkers Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein, emphasizes zoning reform to put America back on track and provide direction for the Democratic Party, which they point out is floundering politically.

The discussion springs from a nationwide push to allow more missing middle housing, and generally higher density, in currently restrictive land-use areas. A coalition of urbanists, YIMBYs, and affordable housing advocates supports it.

Zoning reform is good and necessary, but it will only get you so far. There’s a blind spot in these discussions, which focus on housing types, building codes, land-use regulations, parking, and affordable housing subsidies. These are all important topics, but to see that blind spot, look around you. You are probably inside now—so look out the window. What do you see? You almost certainly see a street or streets.

We have paid some attention to streets in the last 20 years through the “complete streets” movement. More than 1,700 jurisdictions across the US have adopted “complete streets” policies, including 37 states. Complete streets policies have failed to make our streets safer. These policies coincided with skyrocketing pedestrian deaths, which have risen 82 percent from 2009 to 2021. Such policies, which say that streets should serve many kinds of users, have failed to change streets much outside of core cities in major metro areas.

Unlike housing and zoning, streets resist reform. If nothing is done to purposefully change streets, they will stay the same for hundreds of years. The Manhattan street grid was laid out in 1811, well over 200 years ago. Some changes have been made—particularly to accommodate evolving transportation technologies—but fundamentally, the geometries, particularly block sizes, have changed little over the years.

Complete streets policies focus on individual thoroughfares, but streets are networks, all linked up. Individually, streets are nothing, like a computer without the Internet. We radically changed our approach to streets in the middle of the 20th Century, including widening many commercial streets for automobiles and bulldozing freeways through cities, but the biggest change was made to new streets. In a relatively short period, all across America, we abandoned the grid, or connected network, which had created the bones of towns and cities of all sizes, from Manhattan down to little villages in the countryside.

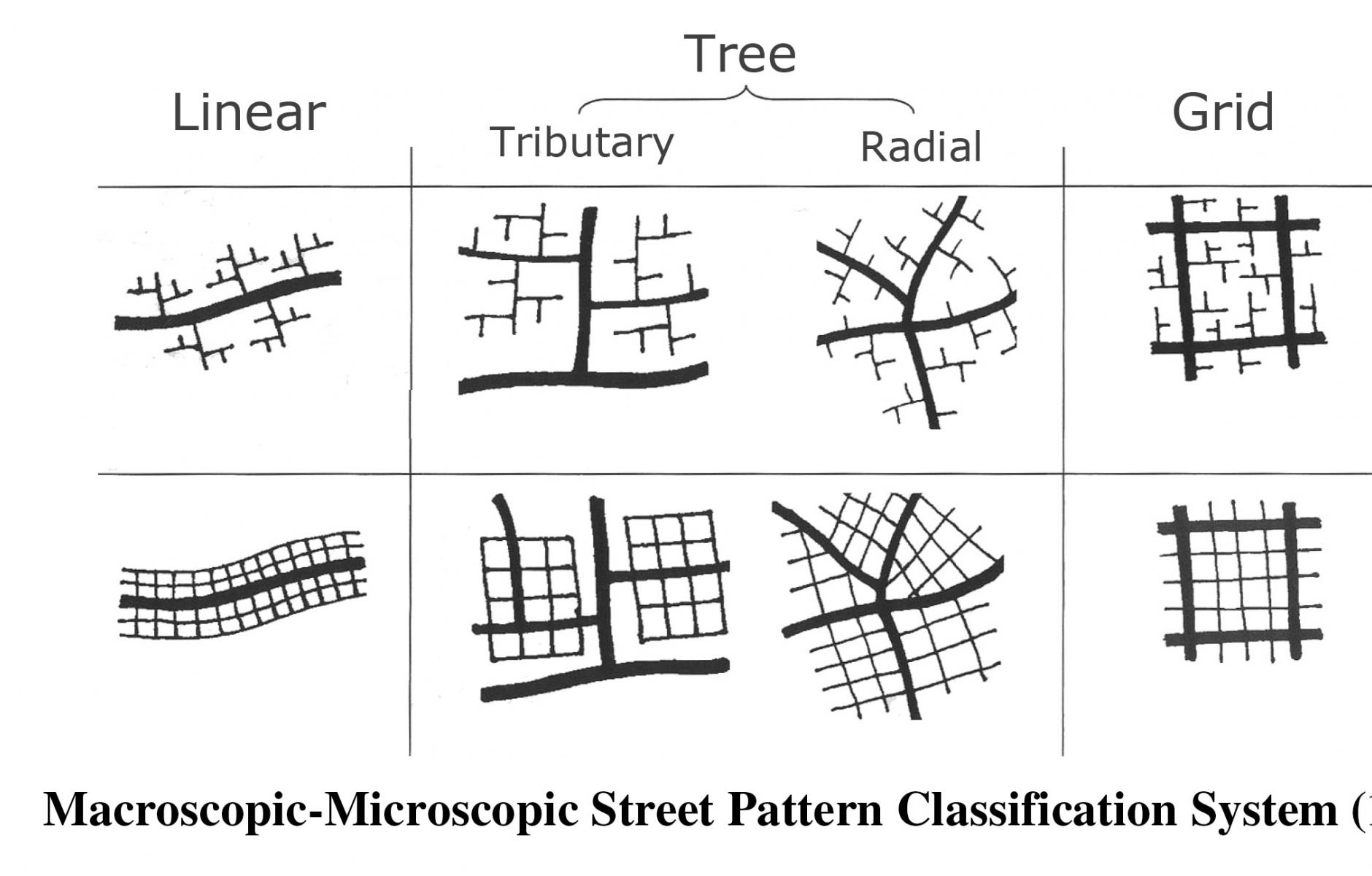

Replacing that grid was a dendritic, or tree-like system of arterial roads and separate pods of housing, commercial, and civic uses branching off of the main, or trunk, thoroughfares. This change happened so fast, so thoroughly, and it was embraced by the population that moved out of cities into the suburbs. Within two decades, we had forgotten how to build connected street networks. The late great Christopher Alexander decried this change in his influential 1965 essay “A City is Not a Tree.” Although this was a landmark text in architecture and urban design, it failed to influence traffic engineers and transportation planners, who are in charge of the purse strings of street construction through federal, state, and local departments of transportation.

If you examine historical images of metro areas in 1950, the vast amount of developed land was built on street grids. Up to that point, providing new land for community development was easy—just extend the street grid in any direction. Because development on the grid was compact, adjacent, and mixed, it didn’t take up that much land.

After 1950, it was a whole different story. The dendritic pattern created housing of a different sort. The vast majority was single-family housing on larger lots than were typical in cities. Multifamily was built in large complexes. Everything was spread out, with housing types and uses separated so that you need a car to get from place to place. That requires more parking, increasing distances and further hindering walking.

Twentieth Century Canadian intellectual Marshall McLuhan said, “The Medium is the Message.” Communication changes when we shift technology, like from print to broadcast news and then to the Internet. The message is determined, at least to a significant degree, by the medium in which it is carried.

For housing, the medium is the street network. Yes, zoning codes have a big impact, but not as big an effect as the bones of the community, which consist of the streets. Over the last three decades, new urbanists have been the most influential reformers of land-use codes through the concept of form-based codes. New urbanists have placed equal emphasis on streets and have only really succeeded when they have achieved a connected network.

However, the street network idea has been less influential than code reform. When housing advocates talk about zoning reform as a critical aspect to boosting the production of more affordable housing, they never mention street grids. They seem to think that housing pops up from zoning abstractly, rather than built on a street, which is essential in housing form and how it affects human inhabitants.

There are dozens of studies on the impact. For example, new urbanist civil engineers Norman Garrick and Wes Marshall showed that gridded, compact street networks reduce traffic fatalities by three times, compared to fully tree-like networks and associated design characteristics. Another study showed that the grid produces a 15% reduction in obesity rates, a 10% reduction in high blood pressure rates, and a 6% reduction in heart disease rates.

Street grids are healthier, but they also affect our social lives and the kinds of housing built. History shows us that a greater variety of housing comes more naturally on a street grid. That also affects walkability and the options for multimodal transport. That affects household budgets through lower transportation costs.

Street grids are the most natural and efficient way to develop. I go to a festival once a year where participants set up a community of tents and RVs, with a whole town of services complete with food and retail, primary health care and sanitation, built by staff and participants in hours. Do they build cul-de-sacs? Of course not. It’s a grid! Most of them live and work in dendritic street systems, yet a grid is the obvious choice when it comes to building a temporary community quickly. It's a nearly impossible dream under our modern transportation planning regime. To create abundance in housing and healthy communities, we need to reform street networks, not just zoning.