When borders blur

There are regions in this country where collaboration is a baked-in part of the culture. Where the towns share water systems, school buses, housing plans—and maybe even optimism. And then there are places where the idea of “regional planning” gets stuck in the gears of local politics, conflicting regulations, or sheer habit.

New England, despite its patchwork of fiercely independent municipalities, is proving to be one of those rare places where collaboration not only happens—it sticks. And for those of us doing this work in regions where alignment is harder won, it’s worth asking: What’s happening up there that makes regionalism not only possible but pragmatic?

That’s what makes this year’s CNU33 in Providence especially well-timed. At a moment when regional coordination feels both necessary and elusive, New England offers working examples—and the Congress offers a front-row seat.

New England gets it done

Let’s be clear: New England’s success isn’t because the work is easier there. It’s because necessity has forced creativity. Historic settlement patterns, aging infrastructure, and fragile ecosystems demand coordination. What’s changed is that planners and local governments are starting to design governance around those needs—not the other way around.

Take Cape Cod. If any place has a reason to stay local in its thinking, it’s a string of 15 distinct towns clinging to their identities like lobster traps on the jetty. But the Cape Cod Commission has managed to steer those towns toward a shared strategy for tackling housing. It didn’t happen by waving a mandate from Boston—it happened through dogged engagement, data-sharing, and the formation of a regional housing trust with skin in the game from everyone. Now, with the Housing Cape Cod strategy, they’ve mapped out where housing can go, how it gets funded, and how it can actually serve the people who need it—without every town reinventing the wheel.

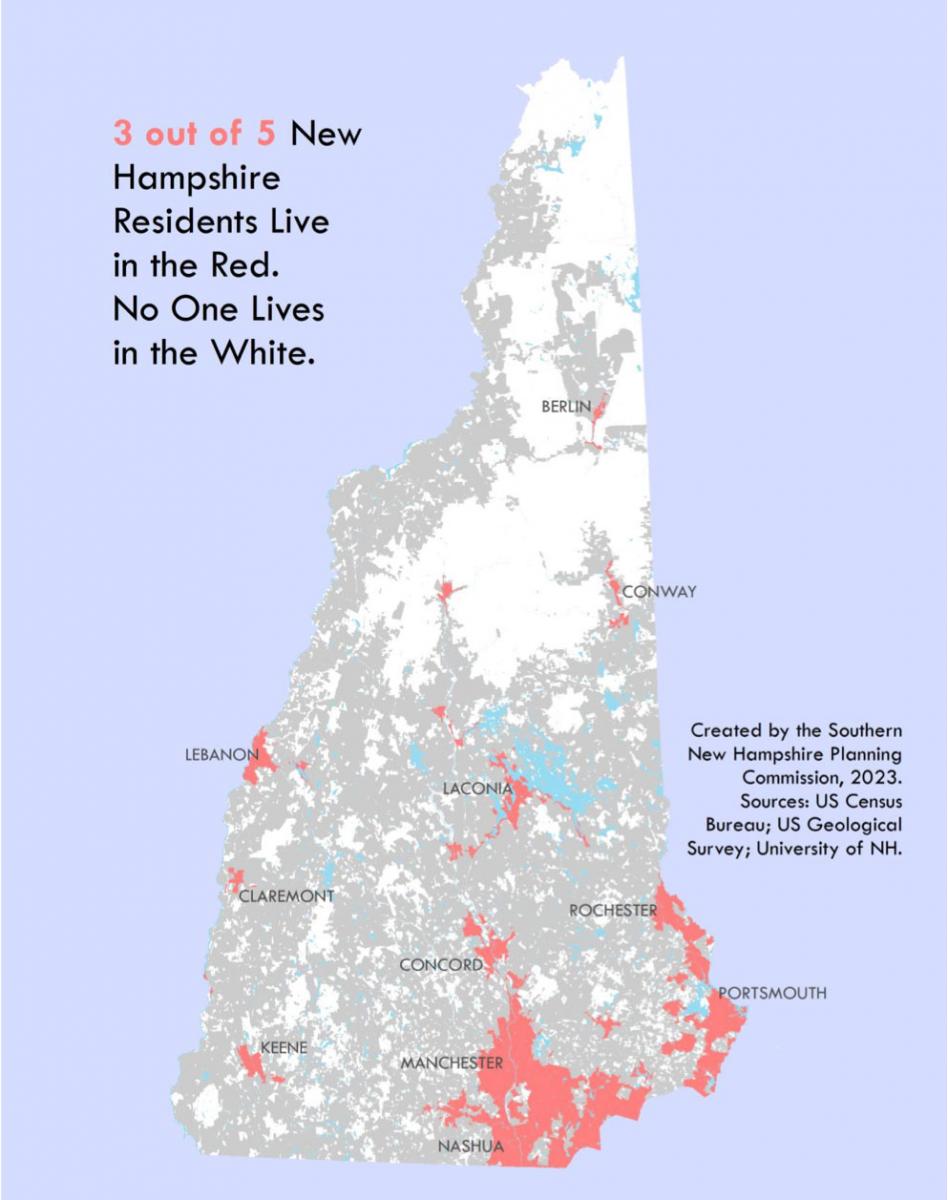

Head north and inland a bit, and you’ll find the Southern New Hampshire Planning Commission taking a similarly pragmatic tack. This isn’t a region where folks are clamoring to give up local control. But it is a place where people recognize the limits of going it alone. That’s why their Regional Housing Needs Assessment isn’t just a data dump — it’s a conversation starter. It gives all 14 member communities the same foundation of facts: where the housing gaps are, what the demographics suggest, and how local decisions can be calibrated to serve regional needs. It’s not top-down; it’s collective common sense. What makes it work? Mutual benefit. When you know the people at the next table are working from the same numbers—and facing the same public pressure—the path to consensus shortens. It’s the same sort of magnet to development as restaurant rows are to diners—builders know they’ll probably find something that fits their market niche.

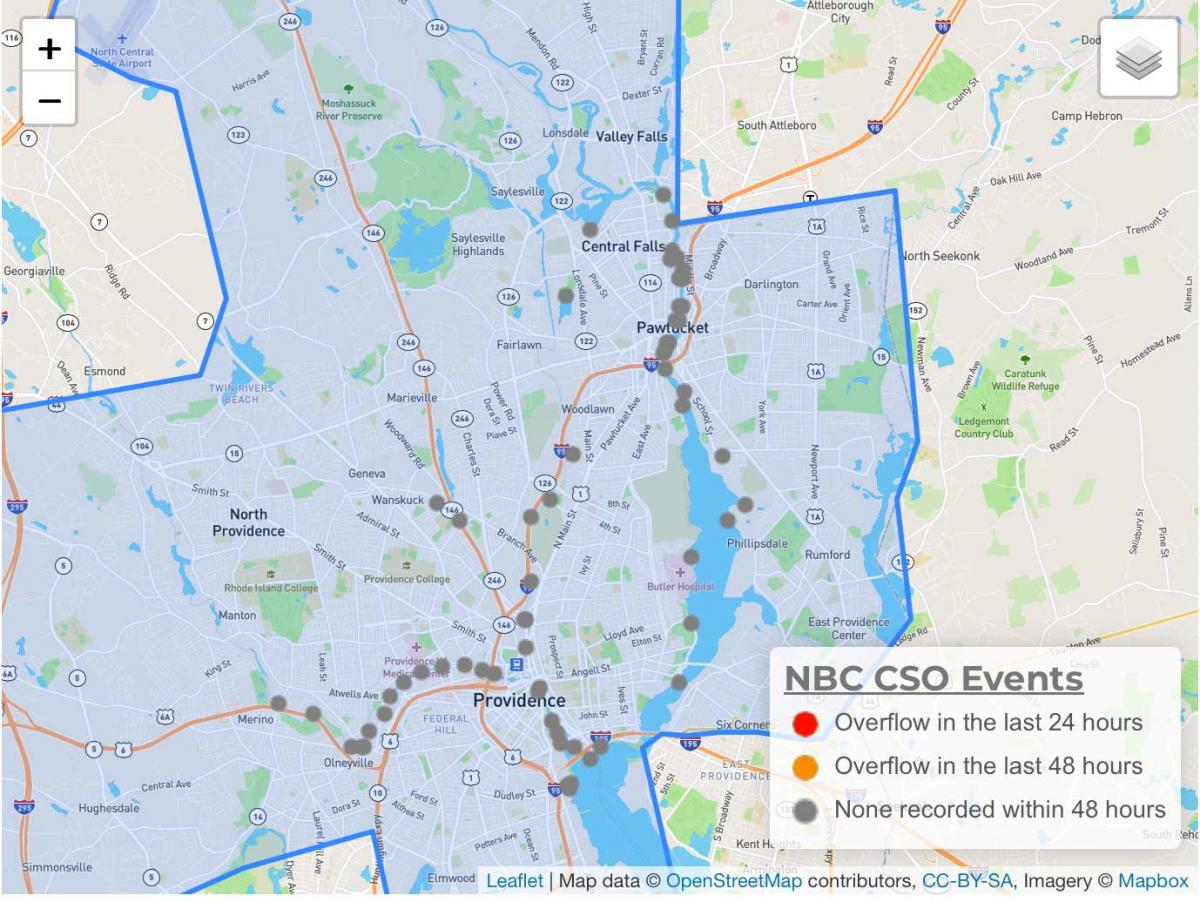

Infrastructure’s a different beast, and the people at the Narragansett Bay Commission have been wrestling it for decades. They manage the lion’s share of Rhode Island’s wastewater treatment—two massive plants that handle everything from urban runoff to industrial discharge. But what’s most impressive isn’t just their engineering—it’s their planning horizon. They're not just reacting to overflow crises. They're thinking in 50-year timelines, using consent agreements and clean water regulations as opportunities to invest wisely and proactively in a shared natural resource. Nitrogen removal, estuary protection, and climate resilience—this is work that makes the invisible visible, and reminds us why regional systems matter in the first place.

And then there’s stormwater—the hydrologic cousin no one used to talk about. In western Massachusetts, a coalition of communities organized through the Connecticut River Stormwater Committee has stepped up in ways that might not make headlines but absolutely shift outcomes. Bound not by town lines but by the watershed they share, these communities collaborate on public education, data collection, and regulatory compliance under the EPA’s MS4 permit. It’s wonky work. But it’s vital. And by coordinating across borders—with help from the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission and University of Massachusetts — they’re turning stormwater from a bureaucratic burden into an organizing principle.

Why this isn’t just a New England story

It’s easy to treat these successes as regional quirks. After all, New England has home rule, centuries-old towns, and political structures that look nothing like what you’ll find in, say, the Deep South or the Mountain West.

But here's where it gets interesting.

Even in places with very different political and physical geographies, the same pressures are mounting. In Northwest Arkansas, for instance, local governments and major employers have worked together through the NWA Council for more than three decades—on transportation, economic development, and shared branding. That kind of cohesion is rare, and it’s helped the region become one of the fastest-growing in the country.

And yet, even with all that collaboration muscle, wastewater and stormwater planning have proven harder to regionalize. Not because of bad actors or lack of will, but because the institutional frameworks that make it easy to work together on roads and jobs haven’t extended to water and land use. There’s no stormwater equivalent of the regional mobility authority. Yet.

That’s the point. If a region like NWA — with its private-public alignment and culture of collaboration — still hits bureaucratic and regulatory walls, what can we learn from New England, where those walls are being restructured?

What you will see at CNU33 (If you are paying attention)

This is the spirit animating CNU33 in Providence — not just a conference, but a chance to witness regional planning that works in practice.

On paper, you’ll find sessions on zoning reform, housing affordability, climate impacts, and transportation planning. In person, you’ll find something more powerful: planners, advocates, and local officials who are figuring out how to stitch together jurisdictions, priorities, and budgets in a way that reflects how people actually live and move through their communities.

It’s not just a New England event. But it’s definitely a place to study what New England is getting right—and how those lessons might translate elsewhere.

This article was published on the Placemakers blog.