Dissolving border vacuums, part 4

Last time we discussed solutions for sunken railroad and highway corridors, so this time let's look at their elevated corridors. Over the coming months we'll look at solutions for many other kinds of border vacuums and see if they could apply to Baltimore.

When there's no farmers' market, the JFX isn't a place you'd want to linger.

More Chinese walls

As with their sunken corridors, elevated railroad and highway corridors often form desolate border vacuums. But as Steven Dale argues, this doesn't mean they're inherently inhospitable: “Any long and narrow border is easily fought by increasing connectivity of uses across the two sides via careful and intentional design interventions that overwhelm the border. So while people lament things like elevated expressways and viaducts, that’s due more to a lack of imagination and creativity than any objective understanding of the problem. We need to stop making them out to be the monsters they aren’t.”

As with the sunken corridors discussed in the previous post, most US cities never really bothered to integrate their elevated railroad and highway corridors into the urban fabric. But it only takes a little creativity to transform even the most unpleasant elevated corridors into unobtrusive, porous, and even pleasant amenities.

The JFX is easily forgotten when the farmers' market is in session.

Semipermanent programming

One relatively simple, but limited, first step to dissolve an elevated transportation corridor is to inject (more) programming under it, like flea and farmers' markets, recreational facilities (i.e. basketball and tennis courts), festivals, and any number of other community activities. Don't just relegate the space to parking or turn it into ambiguous “open space” – that only reinforces the viaduct's vacuum effect!

The wonderful Sunday farmers' market under the JFX is a great start, but it also reflects the limitations of the programming strategy: once the program ends, the border vacuum returns! The JFX vacuum is overcome for ~five hours a week (and only from April to December), but it returns in full force for the other 163 hours of the week. Furthermore, the market only occurs under a small portion of the JFX: the more viaducts a city has, the harder it is to inject enough programming to overwhelm all their border vacuums.

Any meaningful dissolution of an elevated border vacuum thus requires frequent, constant, sustained programming, which isn't always so easy to do. Not only that, but the programming requires the aforementioned mixed-use context to be viable. For example, there already are far too many vacant, graffitied basketball courts and concrete “open spaces” under viaducts in cities across the US (at least in those areas that haven't just been relegated to parking): the gloomy ambiance of the viaducts may dampen one's desire to use those amenities, but most sit empty because there are no (or not enough) adjacent neighborhoods to activate them. Contrary to popular belief, the neighborhood determines the success of the amenity, not the other way around!

So to support any meaningful viaduct programming, a city would need to introduce Jacobs' “extraordinarily strong counterforces” (discussed in the previous post) by building as much mixed-use infill as possible as close to the viaduct as possible. The ambiance from the mixed-use infill and viaduct programming might even overcome the noise from the cars or trains above. This outcome still might not appeal to some – many people quite understandably don't want to live near train tracks and highways – but it certainly wouldn't be an issue among youngsters hungry for street life: the banal viaduct would simply be overwhelmed by all the delightful stuff under and around it!

Cross streets

In addition to the adjacent infill and programming, it's important to introduce as many cross streets as possible under a viaduct. This allows pedestrians to pass underneath it in more places by eliminating superblocks. Right now, for example, there are only four crossings under the JFX on the east side of downtown, and, assuming the viaduct remained intact (though there are numerous possibilities for realignment or removal), additional cross streets could be introduced underneath it quite easily.

Of course, cross streets won't facilitate movement across/under a viaduct if they're boring, unpleasant, or (perceived to be) dangerous – they'd be no better than the forbidding pedestrian bridges and dreary overpasses across sunken highways. Furthermore, if there's nothing on the other side of a viaduct (or a sunken corridor) worth crossing for, then cross streets won't accomplish much either.

But assuming there is a viable urban fabric on both sides of a viaduct, then, in order to function as pleasant, safe, comfortable, and easy crossings, any cross streets underneath it would probably need to be lined with permanent programming akin to the bridge liners discussed in the previous post:

A Tokyo railroad viaduct doubles as a line of shops.

Permanent programming

If a viaduct is surrounded by infill and crossed by multiple streets, the semipermanent programming underneath it can gradually be replaced with more permanent infill. Although this strategy was occasionally used in the US, it's far more common (and usually better done) abroad – Berlin's railroad viaducts are an excellent case in point. (I still remember a surreal experience in a supermarket underneath a railroad viaduct in Berlin – somehow the rumbling trains never managed to shake the bottles from their shelves!) Philly's Reading Terminal Market is another great example: built underneath a gigantic (former) train shed, the market is wonderfully integrated into the surrounding urban fabric. Even the cross streets underneath the train shed, albeit being a bit gloomy, are artfully lined with shopfronts.

Of course, highway viaducts and steel railroad viaducts are noisier than older masonry viaducts, so infilling underneath them might require soundproofing. On the other hand, the spaces under the former offer greater flexibility of use – you're not constrained by a series of fixed and relatively small arched bays.

So could this strategy apply to the JFX? So far the JFX border vacuum has only attracted more border vacuums: giant parking lots, an ever-expanding prison complex (plus the Juvenile Justice Center further south), a gigantic postal facility, and numerous facilities for the homeless (shelters, soup kitchens, clinics, treatment centers). It's difficult to imagine fixing this vast array of border vacuums, but they must be fixed if Baltimore wants a strong connection between the east side and downtown. Some of these facilities, such as Our Daily Bread, actually are good urban buildings (i.e. built out to the sidewalk without resorting to blank walls), so it is possible to work around them with dense, complex infill (Jane Jacobs' “extraordinarily strong counterforces” again) that might be able to overwhelm the current institutional programming.

Assuming the city (1) carefully surrounded the above border vacuums with appropriate infill (we'll look at specific solutions in upcoming posts on institutional border vacuums), (2) continued its admirable effort to increase the downtown population, and (3) undertook additional infill and adaptive reuse on the western edge of the JFX, then it might be possible to gradually fill the space under the JFX with permanent programming that could be supported by all the surrounding infill. The parking area that currently hosts the farmer's market, for example, could be rebuilt as a multipurpose market corridor and eventually turned into a permanent market.

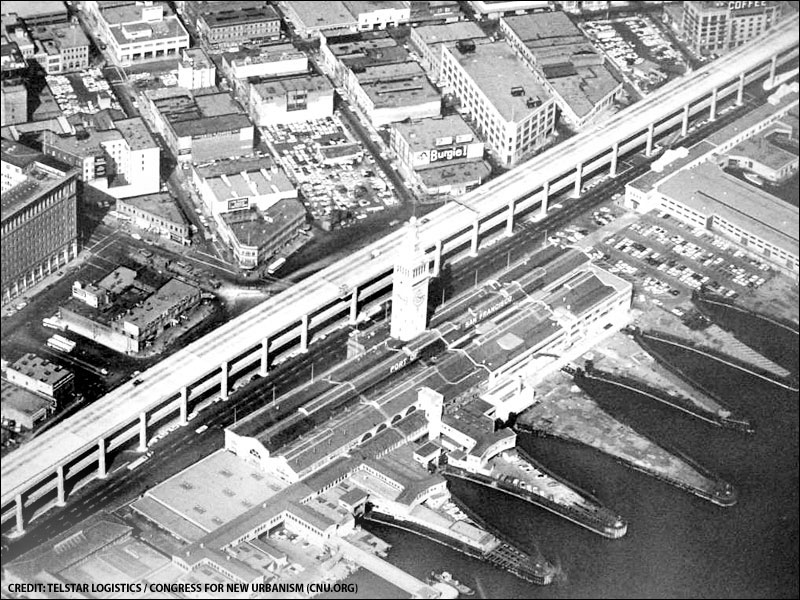

A view of San Francisco's former Embarcadero Freeway in 1960.

Boulevardization

Highway viaducts can also be dismantled and replaced with boulevards. Contrary to commonly-espoused doubts, the strategy has never yet resulted in traffic armageddon, so I think any doubts should be directed towards the far more important question of what exactly will replace the highway? Would the replacement be an urban amenity, like San Francisco's Embarcadero, or would it merely be a different kind of highway, like a single-use arterial?

For example, there's a longstanding proposal to tear down the elevated portion of the JFX and replace it with a boulevard that could allow East Baltimore to reconnect to downtown. I think the proposal sounds fine in the abstract, but its implementation raises some legitimate skepticism. Firstly, how would all the surrounding institutional border vacuums discussed above be addressed? Furthermore, many of the existing “boulevards” in Baltimore – like MLK Boulevard and President Street – have failed to attract abutting infill and pedestrians because they're essentially just glorified arterials, so would this failure merely be repeated? Replacing the JFX with an extended President Street (i.e. an extended arterial/collector road) would probably be a waste of time, money, and other resources that could be better deployed elsewhere.

If, however, the JFX was replaced with a true multiway boulevard that had the ability to attract abutting infill and street life, and if the institutional border vacuums in the area were successfully addressed, then its removal might indeed be a worthwhile effort. I've also suggested replacing the JFX with a boulevard+canal combo that could transform the currently-covered Jones Falls into a recreational canal similar to San Antonio's River Walk. (The proposal is admittedly rather idealistic because it would require additional expensive solutions for CSO, water pollution, and flood control problems, among many others.)

Adaptive reuse

Again, as in the discussion on sunken corridors, most of the solutions above assume that the elevated corridors in question need to remain intact. But if they don't, their viaducts can be dismantled relatively easily and replaced with traditional urban fabric. However, if the viaducts have some intrinsic architectural appeal – like abandoned masonry or steel railroad viaducts – it might be a better idea to transform them into civic assets and neighborhood centerpieces.

The Promenade Plantée and Viaduc des Arts in Paris.

Paris' Promenade Plantée is an excellent case in point: a disused masonry railroad viaduct was transformed into a linear park and the archways beneath it were filled with artists' studios and shops. New York recently transformed a disused steel railroad viaduct into a beautiful linear park as well. Not every disused viaduct is worth saving, especially if repairing it would be prohibitively expensive, but most of them require just a little creativity to be turned into civic assets.

Of course, as discussed earlier, disused viaducts need to be integrated into the urban fabric just like active viaducts – mixed-use infill should be brought right up to the viaduct, multiple cross streets should be introduced underneath it, and any remaining space underneath it should be programmed or infilled. Furthermore, in order to avoid isolation, the amenity atop the viaduct (i.e. the linear park or promenade) should physically and visually connect to the underlying street grid in as many places as possible.

I hope you've enjoyed this final installment on transportation border vacuums – next time we'll move on to institutional border vacuums by discussing solutions for congregational facilities, like arenas, sports facilities, and convention centers.

This piece originally appeared in the EnvisionBaltimore blog.

For more in-depth coverage:

• Subscribe to Better! Cities & Towns to read all of the articles (print+online) on implementation of greener, stronger, cities and towns.

• Get the March 2013 issue. Topics: City returns to streetcar roots, market shift to urban lifestyles, sprawl lives, Housing boom for the creative class, Retail prospects, Main Street of the Bronx, Green space for transit-oriented project, Multigenerational housing, Architecture of place, New Orleanse freeway redevelopment

• Get New Urbanism: Best Practices Guide, packed with more than 800 informative photos, plans, tables, and other illustrations, this book is the best single guide to implementing better cities and towns.