Filling in the ‘Missing Middle’: No new wheels, please

For lots of reasons, including the ones PlaceMakers’ Scott Doyon explains here, Seaside, on the Northwest Florida Gulf Coast, makes a great place to talk about the appeal of small-scale dwellings in small-lot neighborhoods. Certainly, hanging out in a place where the real estate market has bid up the price for small wooden houses without lawns or garages to six and seven figures makes it harder to argue that nobody will pay for the privilege.

Location, then, partially explains why some 30 prospective developers — and Bandit, the dog — arrived over the weekend to drill down on how-to topics related to just such places.

Here’s Bandit.

Bandit appears a little confused, owing perhaps to his years. The rest of the crowd had a right to feel overwhelmed, owing perhaps to the depth of the weekend’s dive into parcel identification, design, finance, construction supervision and property management. It felt like a semester’s worth of grad seminars crammed into 15 hours over two days. Which only drove home the recurring weekend theme: Better do your homework.

The Seaside workshop was part of an expanding series of “Boot Camps” by the Incremental Development Alliance. Most prominent among its organizers is John Anderson, who, over the last three years or so, has been hammering home the message that there’s room in real estate development for a new generation of developer/builders willing to master the details of right scale, right place and right plan.

Filling out the Boot Camp faculty: Anderson’s partner, architect David Kim; Dallas developer Monte Anderson (no relation to John); and Mississippi architect/planner/developer Bruce Tolar, who’s earned his own hard-knocks education in the design and development of infill cottage neighborhoods.

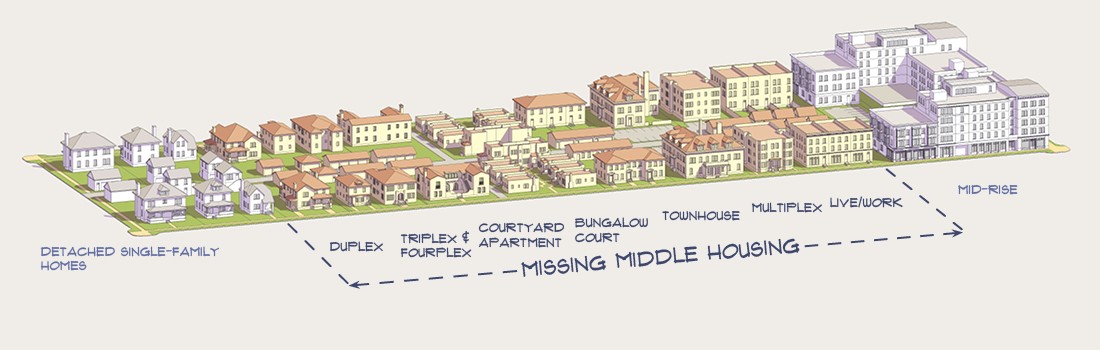

The supply-side coaching these guys offer serves an important segment of the accelerating demand for “missing middle” housing, a term popularized by Opticos Design’s Dan Parolek. Parolek created a cool graphic to illustrate the choices absent from what used to be the full menu of for-sale and rental housing in America.

Opticos’ “Missing Middle” site has plenty of resource material to deepen understanding of why choices shrunk. And for a splendid context setter, check out Amanda Kolson Hurley’s piece in the Next City blog:

We used to build lots of in-between housing in this country: rowhouses, duplexes, apartment courts. In other countries, the middle is still the default. Britain is the land of the semi-detached house; the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark have dense, low-rise (and attractive) housing of various kinds. But the United States stopped building this way decades ago.

The result, critics say, is huge unmet demand from millions of people whom our bifurcated housing supply doesn’t serve. Young families are priced out of new single-family homes, which now have a median size of a whopping 2,453 feet, but can’t squeeze into studio or one-bedroom apartments. Older adults want to downsize and economize without giving up their own front door or a patch of garden. Lower- and middle-income Americans struggle to pay climbing rents while new housing is increasingly marketed as “luxury.”

As of 2014, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 63 percent of the nation’s 117 million occupied housing units were detached homes. Another 13 percent were apartments in buildings with 10 or more units. Only about 19 percent of America’s housing stock is composed of all the types in between, from attached single-family (aka townhouse) up to nine-unit multiplex. It hasn’t always been like this — as recently as 1986, 20 percent of all new single-family homes sold were attached, rather than detached; by 2014, that share had dropped to 10 percent.

The squeeze on renters and prospective home buyers is now so obvious that major players – experienced multifamily developers, non-profit and government affordability advocates and a few financial power houses – are looking for ways to repopulate the middle ground in big, broad strokes. Which requires reforming a lot of regulatory, finance and construction processes that have knotted themselves into an industry specializing in mega-buck downtown development and mega-acre suburbs. Deconstructing and reconstructing all that will take a while. Meanwhile, the supply/demand gap is only growing.

What Anderson and company are up to is something more immediate and surgical: A rigorously reality-checked approach pledged to inventing no new wheels.

The idea is to max out the potential of existing zoning, financing, design and construction processes and to do it at scales unlikely to freak out adjacent neighbors or trigger complicated review processes. Hence the focus on accessary dwelling units, duplexes, small apartment buildings and cottage courts.

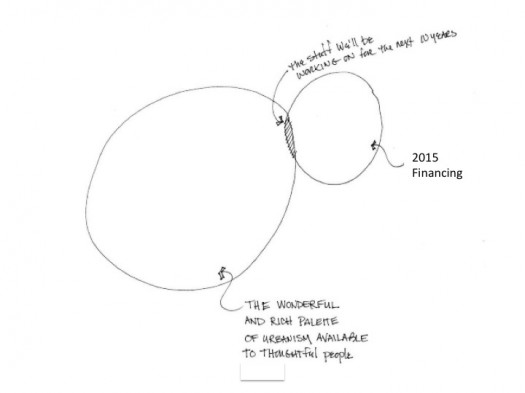

It’s not about abandoning goals for housing that serves more people at broader ranges of income; it’s about getting there by taking smaller steps. And that begins by getting very real, very fast. Here’s one of Anderson’s visual aids in support of that message:

“Form follows finance,” says Anderson, who adds that the tiny overlap in the illustration between urbanists’ dreams and real estate finance realities “is actually so small that we had to blow it up many times over for it to be visible to the naked eye.”

The appeal to hard-edged reality works, especially for architects, urban planners, builders and other pros who’ve been beaten up trying to go big with their idealism. Better maybe to identify projects at scales likely to get financed and built in reasonable time frames. Make them models that inspire replication. Change from the inside out.

The demand for this sort of coaching is strong and growing. For just as small-scale options have faded from the housing mix, so has the supply of professionals with the expertise and experience to bring them to market. Anderson and his team can’t schedule these sessions often enough and in enough places to meet the demand. The Facebook group Anderson created to encourage conversation about these topics has grown from a couple dozen to more than 1,500 members since the summer of 2015.

You can keep up with the progress of this group and others on the Incremental Development Allicance site. Or here in the broader movement for Lean Urbanism. Or here among the projects influenced and encouraged by the Congress for the New Urbanism.

This article first appeared on the Placeshakers blog.