by Bruce Stephenson

The New Urbanism has invigorated city planning by invoking the tradition of American civic design to solve the conundrum of suburban sprawl. This “Florida-grown movement” originated with Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk’s plan for Seaside; a plan, James Kunstler writes, “straight out of John Nolen.” Nolen, America’s preeminent planner in the early 20th century, is a New Urbanist patron saint. It stands to follow that if the New Urbanism is to fulfill the historic vision it has unearthed, the visionary plans Nolen produced in the “great laboratory of town and city building,” as he called Florida, requires scrutiny.

In 1919, Nolen stood at the apex of his profession. He had edited two books, written two others, published over 50 articles and plans, and presided over the nation’s largest planning firm. Nolen’s success stemmed from a blend of idealism and business acumen, which gave his work an innovative, yet pragmatic bent. Still, the difficulty in implementing plans made him feel more a missionary than planner.

Two years later, Nolen concluded that re-planning the American city was hopeless. The nation’s cities were “cursed,” he wrote, “with nearly insolvable social and political problems.” To complicate matters, planners seemed more intent on drawing up zoning ordinances that secured mediocrity rather than on implementing new models for a nation that had over half its population classified as urban. After this revelation in the 1920 census, Nolen initiated the planning of new towns based on the garden city ideal. In this endeavor Nolen owed much to Englishman Raymond Unwin, the designer of the first Garden City.

From their first meeting in 1911, Nolen and Unwin became fast friends. Close in age and interests, these pioneer planners corresponded regularly for 25 years, exchanging social views, planning expertise, and their visions of a new civilization. Unwin’s plans for Hampstead and Letchworth greatly influenced Nolen’s most lasting presentation of the American Garden City, Mariemont, Ohio.

Designing Eden: John Nolen in Florida

After his initial success with Mariemont, Nolen moved on to Florida to plan what he called, “the last frontier.” In February 1922, he contracted with St. Petersburg to design Florida’s first comprehensive plan. The city, he found, occupied a “site blessed by a benevolent Nature” and possessing “the same characteristics as southern France.” After signing the contract, Nolen wrote an associate, “This seems to be an opportunity to do rather more than we have ever been given the chance to do before.”

In March 1923, Nolen completed an ambitious plan to imbue this “resort city” of 15,000 with a “form and flavor unlike that of other places.” A greenbelt of preserves and parks encircled the lower third (45 square miles) of the Pinellas Peninsula, setting the city’s “natural boundaries” and creating a lure for tourists. He also presented plans to improve traffic connections and establish a Civic Center. Mixed-use neighborhood centers were clustered to prevent the unsightly spread of commercial uses and traffic problems along city thoroughfares. A system of parkways united the city, providing pedestrian access to parks and “local neighborhood centers” with “store groups, churches, and public buildings.”

Nolen’s plan rested on the “adequate control of private development.” He proposed a series of land use controls to insure that development followed the efficient outlay of public facilities, rather than outline speculative desires. Without these regulations, Nolen was hardly sanguine about the city’s future. “It has been said and with reason,” he wrote, “that man is the only animal who desecrates the surroundings of his own habitation.”

In the midst of the great Florida land boom, the desire to make quick profits outweighed any lofty notion of city building. Moreover, the idea of investing public funds to improve the squalid conditions in “the colored section” found little sentiment in a place, where one anti-planning editor advocated replacing black laborers (17 percent of the population) with immigrants from the “agricultural sections of England.” In a referendum, Nolen’s planning initiative received only 13 percent of the vote.

The St. Petersburg experience disheartened Nolen, but he remained optimistic. His firm worked on 54 projects in Florida, including city plans for Clearwater, Sarasota, and West Palm Beach, new town plans for Clewiston and Bellaire, and neighborhood plans for University Park (Gainesville) and San Jose Estates (Jacksonville). In 1925, Nolen finally found in “Venice an opportunity better…than any other in Florida to apply the most advanced and most practical ideas of regional planning.” Nolen planned Venice for the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLE), a labor union looking to capitalize on the land boom. The BLE, however, was also investing for the long term. BLE officials envisioned a regional center for agriculture and light industry, “a place where the ordinary man could have a chance to get all that the rich have ever been able to get out of Florida.”

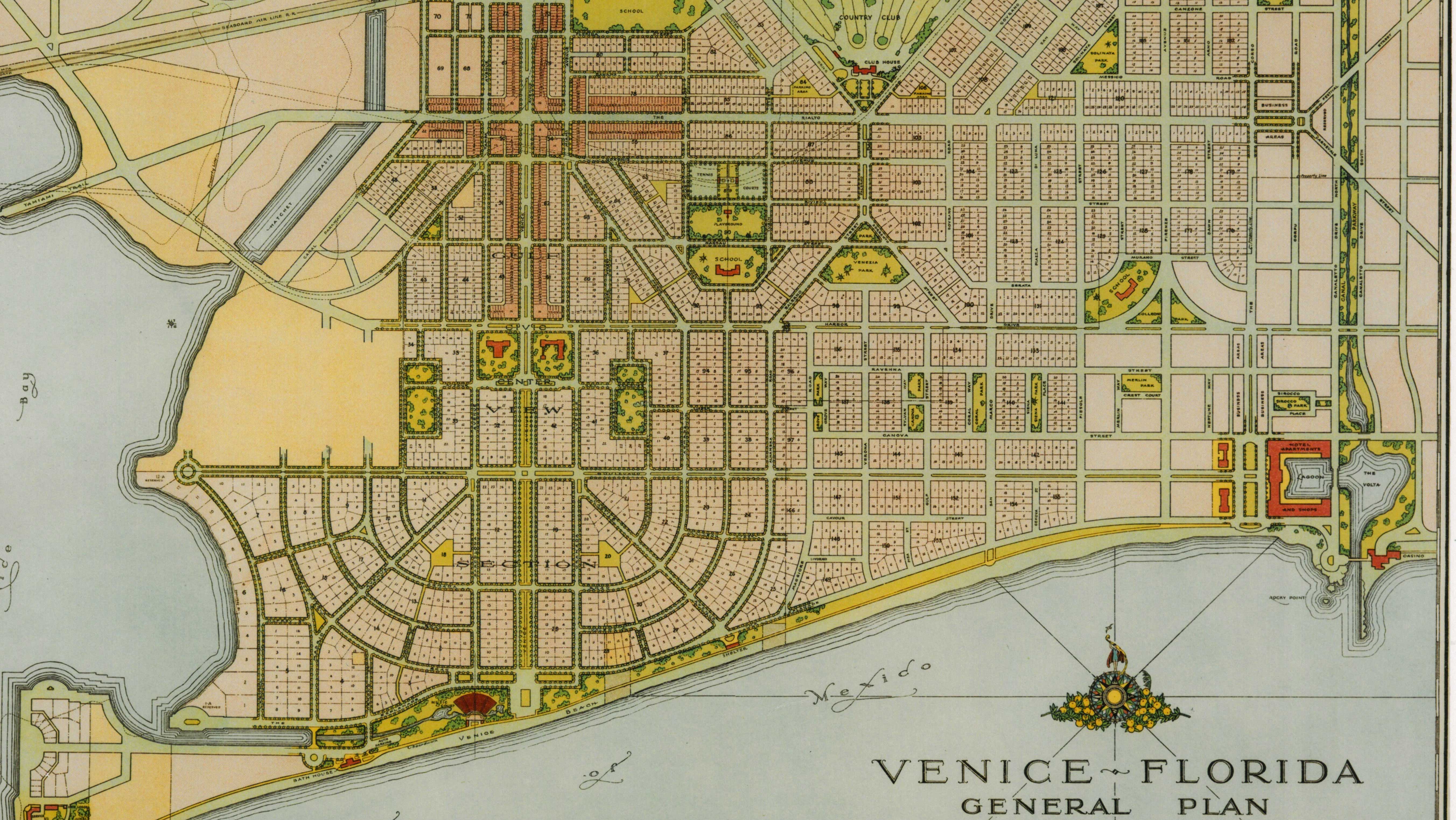

“Nature led the way” and the plan, Nolen wrote, “followed her way.” Greenbelts protected important natural features, and parkways extended from the hinterlands into Venice’s downtown (Figure 1). A greenbelt bounded the town to the east and south, while Venice Bay marked the northern edge and the Gulf of Mexico lay to the west. Nolen paid special attention to the town’s Gulf front location. A linear park ran along the waterfront, with an amphitheater and beachfront park lying at the terminus of Venice Parkway, which connected the beach to the Civic Center.

The Civic Center’s grouping of parks and public buildings offered a view of the Gulf and marked the western edge of the commercial core. From this point east, Venice Parkway narrowed to Venice Avenue, which ran the center of a three-block commercial core between the Civic Center and Rialto Avenue. The Civic Center not only defined the town center, but it stood midway between the commercial core and Venice’s most sublime natural feature — the Gulf of Mexico.

In Venice, Nolen effectively balanced his design between two transcendental ideals — civic virtue and Nature. From City Hall, one could view the palette of Nature while surrounded by the physical form of the “civic spirit.” An ideal site for contemplation, a vision of Nature was always at hand, but it never remained the same, shifting with the tides and the seasons.

Two diagonal avenues defined the neighborhoods lying between the Gulf and the Civic Center. School sites and the commercial center provided focal points for neighborhoods. Common greens and playgrounds were provided in each neighborhood, while a wedge-shaped golf course buffered the eastern section of town from the railway and industrial uses.

Nolen also placed Harlem Village east of the railway, surrounding it with “white farms.” Segregation was a staple of southern life, and if Nolen failed to fight the southern caste system directly, he remained adamant that African-Americans receive the benefits of good planning. In Venice, like other southern cities, he connected African-American neighborhoods to the larger community via a parkway. In cities separated by race, interconnected parkways offered the hope of uniting diverse people through “nature” and to, Nolen wrote, “the brotherhood of man.”

The BLE invested heavily in infrastructure, before the land boom crashed in 1927. Nolen’s plan remained a guiding vision (although Harlem Village was nixed), and Venice stands as the most complete example of the Garden City in Florida. Neighborhoods segregated by class and cost were connected by parkways and linked to the Civic Center. Combining the lines of Nature with a civic orientation, Venice offered, Nolen wrote, “an inspiration to those who would make this world a better place to live.”

At the 1926 National City Planning Conference, held in St. Petersburg, Nolen presented Venice in his presidential address, “New Communities to Meet New Conditions.” More than any other state, Nolen believed, Florida needed “a state plan” to “regulate reasonably” the location of future towns and cities. Nolen envisioned a state of interconnected garden cities based on Venice’s regional and town plan. Although Nolen’s agenda never moved beyond the conference, his vision drew admirers.

A year later, Lewis Mumford, in the keynote address to the same conference, proclaimed, “At least one planner realizes where the path of intelligent and humane achievement will lead during the next generation.” Both Mumford and Nolen advocated regional planning and the new town as the means to channel urbanization into a higher level of civilization. They also saw planning as an art form that revealed mankind’s highest htmirations. “City design” could only “succeed,” Mumford remarked in his conclusion, “when the city planner tries to fathom and express…what the best life possible is.”

The Nolen Legacy

Nolen’s planning ideal fell victim to, what Mumford called, “the departmental routine of the municipal engineer’s office.” Even before Nolen passed away in 1937, civil engineering and social science had replaced landscape architecture as the basis of planning. This shift moved planners to see their profession as a science rather than an art. In 1943, a planning firm hired by St. Petersburg dismissed Nolen’s work as “the optimistic opinion of what the ideal city should be.” Bartholomew and Associates traded Nolen’s Garden City for a more “efficient physical structure” based on a “thorough analysis of the facts.” The plan provided guidance for traffic engineers, but failed to recognize the economic value of “beauty and nature,” the chair of the city planning commission wrote. In 1976, ecological catastrophe forced St. Petersburg officials to adopt an environmentally based plan that closely paralleled Nolen’s.

In 1977, the City Council of Venice dedicated a memorial to John Nolen. The city “built in close conformance with” Nolen’s plan had, the resolution read, “developed into one of the most beautiful cites of its size in the Nation. The Nolen memorial was placed in the Art Sculpture Area, where Venice Parkway intersected City Hall. The only memorial to an American city planner rests, fittingly enough, at a place planned for the contemplation of Nature and the potential of the civic spirit.

The most fitting memorial to Nolen, perhaps, came from Raymond Unwin. In a hand-written note rushed from his New York hotel to Nolen’s deathbed near Boston, Unwin offered his friend “this consolation — The value of your work in the pioneer period of planning over here is recognized and is most highly appreciated in England…I cannot tell you how much I have valued your help, your experience, and above all your personal friendship…I wish there were something more than this poor letter I could do to help you, and in some little way to repay the many kindnesses I have had from you!”

In the 80 years since John Nolen presented his Garden City vision, his assertion that “man is the only animal who desecrates his own habitation” is painfully obvious throughout Florida. Yet, this is not the most troubling point. With inner cities ghettoized and gated subdivisions proliferating, the promise of the good life revolves ever more tightly around flights of escapism. The problem is not just what is walled out, it is what is walled within. Alexis de Tocqueville argued that once a free people isolate themselves from others the bonds of democracy dissolve. This demise is marked by the individual, he wrote, who even when close to fellow citizens “does not see them; he touches them, but he does not feel them; he exists only in himself and for himself alone; and if his kindred still remain to him, he may be said at any rate to have lost his country.”

Yet there is room for optimism. The genius of African-American culture has always been extolling whatever degree of freedom existed to move toward American democratic ideals. Nolen’s vision of a “brotherhood of man,” however hindered by the prejudices of that day, rested on the democratic ideal that immortalized Lincoln and King. The progression of civil rights from Lincoln to King offers hope and, after almost a century, the Garden City still inspires visions of a better community life. New Urbanists have resurrected Nolen’s vision, but the ability of a free people to create a better civic life still remains as much a question of the spirit as of bricks and mortar. September 11th has given Americans every incentive to pursue this vision, but can we muster the faith to believe, like Nolen, “that we could raise the whole plane and standard of the common life, physical, mental and aesthetic…by good planning”?