Grand boulevards would solve the housing crisis, Calthorpe says

Redeveloping commercial corridors into mixed-use urban places could solve the housing crisis, according to Peter Calthorpe, CNU cofounder and urban designer with HDR. “As of right” zoning was adopted for 8 million housing units—two million “market feasible”—on thoroughfares lined with retail, office, and parking in California, Calthorpe told a CNU audience.

As he calls it, the “grand boulevard” strategy could be implemented with a basic form-based code with zero parking requirements. A 15 percent inclusionary zoning requirement would create 300,000 affordable housing units in the Golden State. Those are numbers sufficient to eliminate the housing deficit there, the biggest in the US, he explains.

The “grand boulevard” strategy is at the heart of California’s AB 2011, in effect since July 2023. Grand boulevards could be adopted anywhere in the US, and could meet the housing shortage of between 5.5 million and 6.8 million units, Calthorpe says.

His analysis focused largely on the Golden State, which has the second most expensive housing behind Hawaii, but it has 28 times the island state's population. In 2008, single-family housing production collapsed in California and has yet to recover. “Subdivision and single family is dead,” he says. “Nobody has come up with an alternative. We need something clear and comprehensive, and that is grand boulevards.”

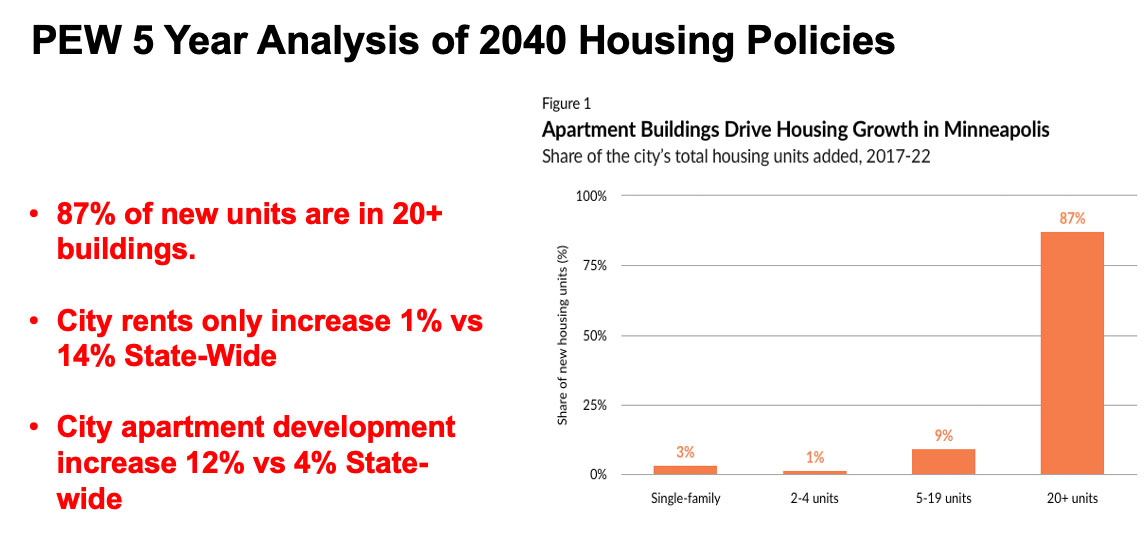

According to research from Minneapolis, Minnesota, grand boulevards compare favorably to missing middle housing, Calthorpe told CNU. Minneapolis 2040 land use reforms, implemented in recent years, apply to missing middle housing and commercial corridors. The 2040 reforms:

- Encourage apartment development on commercial corridors and transit-oriented development (TOD).

- Permit duplex and triplex construction on all residential lots (‘missing middle’).

- Eliminate minimum parking requirements for all new developments.

A Pew analysis shows that the reforms were effective—housing production rose 12 percent in Minneapolis while rents rose only 1 percent. In Minnesota as a whole, housing production rose 4 percent, while rents rose 14 percent. Yet 87 percent of Minneapolis’s housing production was in 20-plus unit projects (commercial corridors and TOD), while only 1 percent was in the 2-4 units range. “Almost zero of these (missing middle) units have been built,” Calthorpe argues. He calls missing middle a “beautiful idea” that works well for new housing developments but argues that it is not scalable for redeveloping single-family lots.

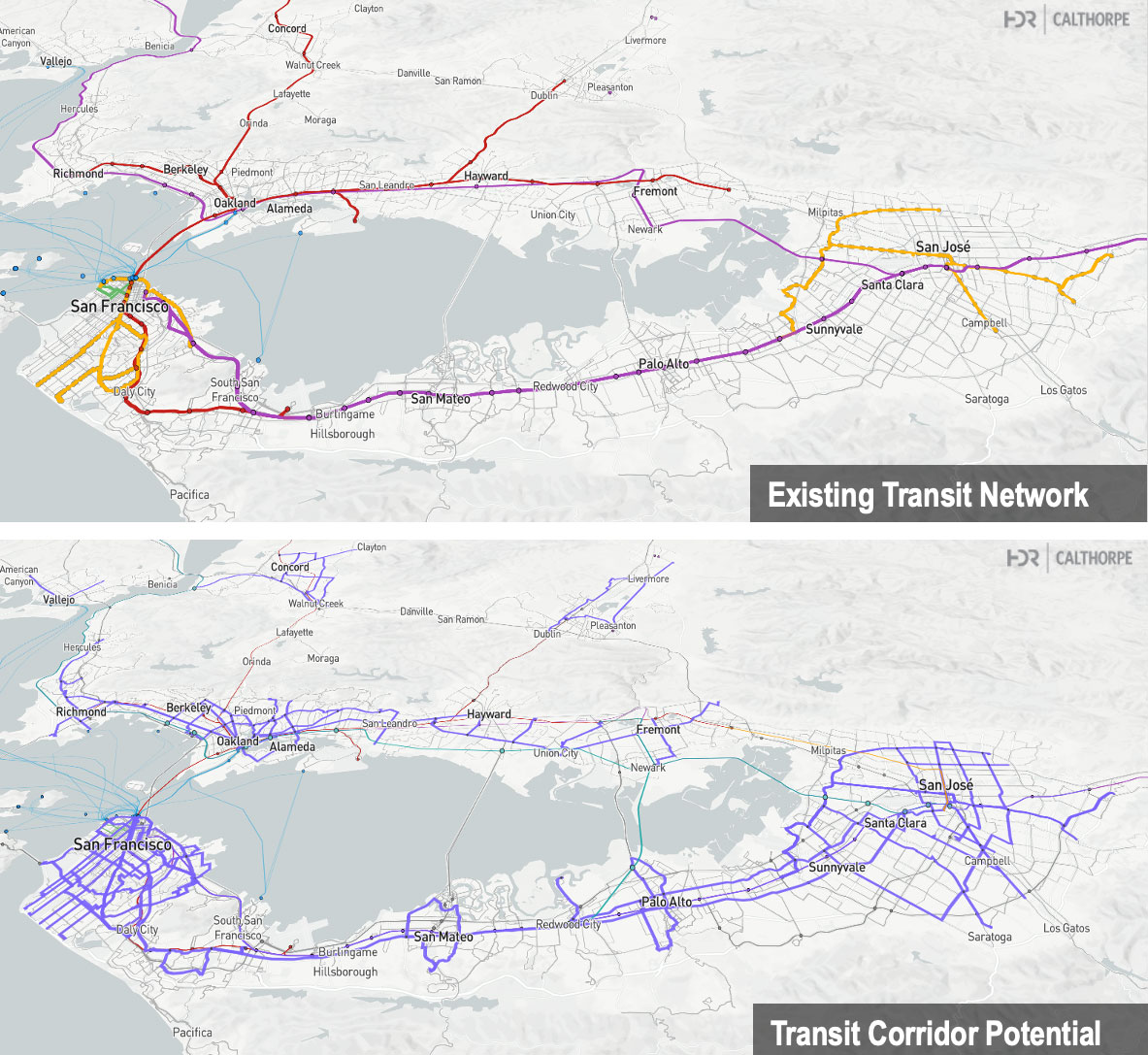

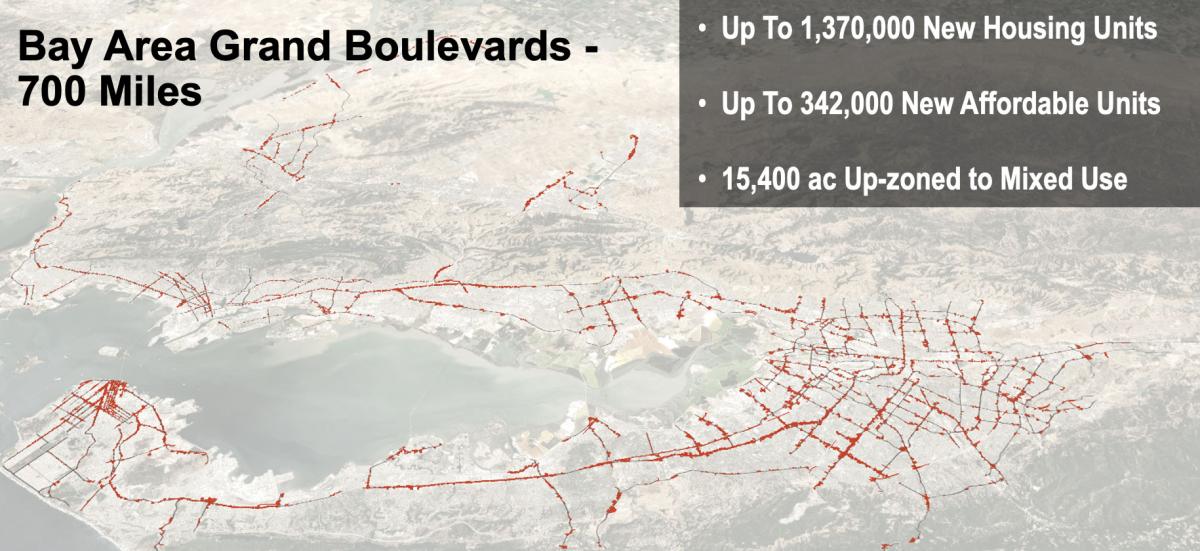

Using Urban Footprint software, Calthorpe analyzed a 43-mile commercial corridor between San Francisco and San Jose, the El Camino Real. Reimagining this as a grand boulevard allows 3,500 acres of infill development, with up to 250,000 dwelling units—some with ground-floor commercial space. Next, he analyzed 700 miles of commercial corridors in the Bay Area, and they could accommodate up to 1,370,000 new infill housing units on 15,400 acres up-zoned to mixed-use. Transit service would be greatly expanded if larger corridors were served with buses. Water use, energy use, driving, greenhouse gas emissions, and household transportation costs could be substantially reduced, he argues.

AB 2011, includes the following form-based standards:

- No minimum parking requirements

- Minimum density 30 Du/Acre

- Maximum Height regulated by street scale and TOD proximity:

4+ lanes—45-foot height limit

6+ lanes—55-foot height limit

TOD—75-foot height limit - Setback requirements:

Front build to zone—80 percent of the façade at 0-10 feet setback

Rear stepback—5 feet for each floor

Side setback—0 feet

Grand boulevards do not impact office and industrial parks, which he calls “the economic engine that you don’t have to touch and don’t want to touch.” He also acknowledges that housing design along commercial corridors leaves much to be desired. “The architecture will be crummy, but we are not going to be the architecture police for this country,” he says. Also, the full vision requires a rethinking of the streetscape, which would be difficult to achieve. In California and Minneapolis, the policy change came first. Street transformation and transit could follow after the “ribbons of density” are built, he says.

Grand boulevards place housing near businesses and solve shelter problems for those who need it most, and, best of all, they do it without displacement, Calthorpe says.