Social life, not density, makes city dwellers happy

I’ve been reading Charles Montgomery’s Happy City, a 2013 book on how city design impacts life satisfaction. Then I came across recent coverage of Culdesac in Tempe, Arizona, and a light bulb turned on. Culdesac is one of the nation’s most talked-about new developments, because the 17-acre neighborhood is notably “car-free.”

Designed by new urbanist Dan Parolek of Opticos Design, occupants live in small multifamily “missing middle” buildings, grouped around courtyards. There is no place for residents to park in Culdesac, and private cars are not permitted on the narrow internal paseos.

The “car-free” aspect has attracted media attention. Residents walk, ride bikes and e-bikes, use car-share and ride-hailing networks, and hop on light rail trains—a station is located at Culdesac’s village center. Many people have moved from other states for the lifestyle. So far, 288 apartments have been built out of 738 total, along with 22 retail spaces (a small parking lot serves retail patrons). The apartments range from $1,300 studios to $2,800 3-bedrooms. Culdesac has a diversity of households, not just young singles.

“Some residents were drawn to Culdesac because of its car-free mission, others in spite of it,” notes The New York Times on March 25. The Times hints at another motivation: “Architects configured the site to maximize shade and encourage social engagement.” While shade is pleasant, the social atmosphere is key to Culdesac’s appeal. A recent Dwell article quotes residents:

“A main walkway extends throughout the property, and our son can spend hours out there riding his bike and we don’t have to worry," explains 35-year-old Ignacio Delgadillo. “And, we actually know our neighbors. We’ve probably made more connections here in six months than when we lived in the suburbs for 15 years.”

That elusive sense of community is a precious commodity and a real draw for millennials and zoomers, like Aryash Dubey, a 22-year-old pursuing a master’s in computer science at ASU who moved into a single-bedroom unit here in April. “I liked the fresh take on housing here and I can take the metro to school in like five minutes max,” says Dubey. “And I was impressed by how friendly the place is. I’ve met plenty of people I probably would not otherwise encounter, including the guy who started the project.”

The sociability comes through in the reporting. The courtyards have a lot to do with it. They are intimate—each serving a small number of units—and linked to a network of human-scale paseos leading to a central plaza where all residents can meet. In other words, Culdesac has degrees of privacy and community, allowing residents to control this aspect of their lives. They can retreat to their unit, hang out in the shady courtyard in view of their closest neighbors, or spend time in the more public paseo. A coworking space, indoor lounge, third-place-type eateries, and events like markets and barbecues offer other opportunities to connect.

Happy City was written well before Culdesac, but its research and anecdotes show that similar designs can positively impact people’s lives, and yet may be under-appreciated. Author Montgomery writes about Rob McDowell of Vancouver, British Columbia, who moved into a downtown apartment with stunning harbor views. At first ecstatic, he invited friends to show off his high-rise pad. Over time, however, “McDowell felt increasingly claustrophobic. His view was no salve for his solitude. ‘You go up the elevator, into your apartment, the door closes, and there you are, stuck alone with your beautiful view,’ he said. ‘I began to resent it.’ ”

Then the developer built a row of townhouses along the podium base of his tower. The townhouses were a “bit cramped,” but they faced a garden and a volleyball court on the third-floor rooftop. McDowell could see the residents playing together. Although the court and garden were available to high-rise residents, none participated.

“After some friends moved into the townhouses, McDowell gave up his view and bought a unit next to them,” the author says. “Within weeks, his social landscape was transformed. He got to know all his neighbors. He joined weekend cocktail and volleyball sessions in the shared garden. He felt as if he had come home.”

Similarly, Montgomery describes a 1973 study of two dormitories at Stony Brook University on Long Island, in which the researchers explored how different designs affect students’ well-being and social experience. In one dorm, students lived with a roommate on floors with a long corridor, a shared bathroom, and a study lounge at the end of the hall. The other dorm was divided into three-bedroom suites, each with a small living/study area. “The students who lived in the corridor felt crowded and stressed out. … The long-corridor design made it almost impossible to choose whom they bumped into and how often. There was no in-between space. You were either in your room or out in the public zone of the hallway.” Unlike the corridor residents, “the suite residents chatted and made eye contact with each other. They reassured each other. They sat closer together.” They experienced less stress and built more friendships.

The living arrangements in Vancouver and Stony Brook were both high-density and multifamily. However, one of each design pair included the opportunity for social interactions and a way for residents to control those interactions. When residents live in places with those characteristics, they are happier.

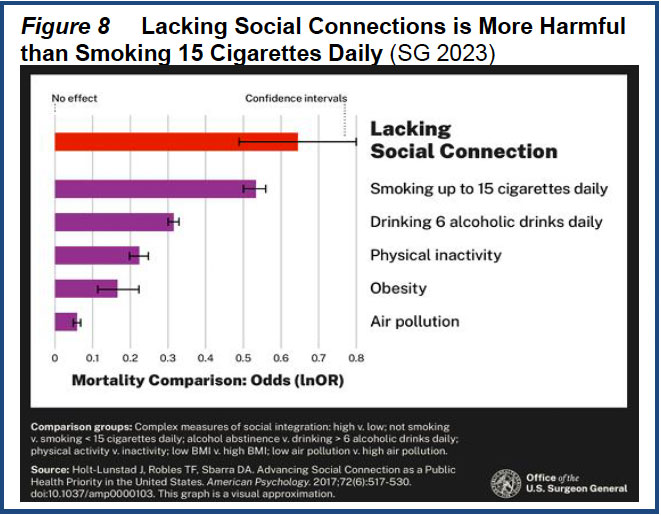

Happy City offers copious evidence that residential and urban design can make people happier if done in specific ways. In fact it is the primary driver of long-term happiness related to community. As the Surgeon General reported in 2023 (see graph above), loneliness is more harmful than smoking or drinking. In other words, people thrive in social living conditions where they have control.

Despite being a low-rise (3-story) neighborhood with small buildings, Culdesac is fairly high-density. When complete, it will achieve about 43 units per acre. Eliminating cars can increase the number of people on a site. Yet, Culdesac also features a plentiful supply of public spaces cleverly designed for social interaction.

Culdesac is sustainable in many ways. You don’t need a car to live there. In a brutally hot city like Tempe, Culdesac allows people to be outdoors in cooler, shady courtyards and paseos.

People are attracted to sustainable design and lifestyle, which draws them in. But they probably stay for the social interaction.