Great idea: Missing middle housing

In celebration of the upcoming CNU 25.Seattle, Public Square is running the series 25 Great Ideas of the New Urbanism. These ideas have been shaped by new urbanists and continue to influence cities, towns, and suburbs. The series is meant to inspire and challenge those working toward complete communities in the next quarter century.

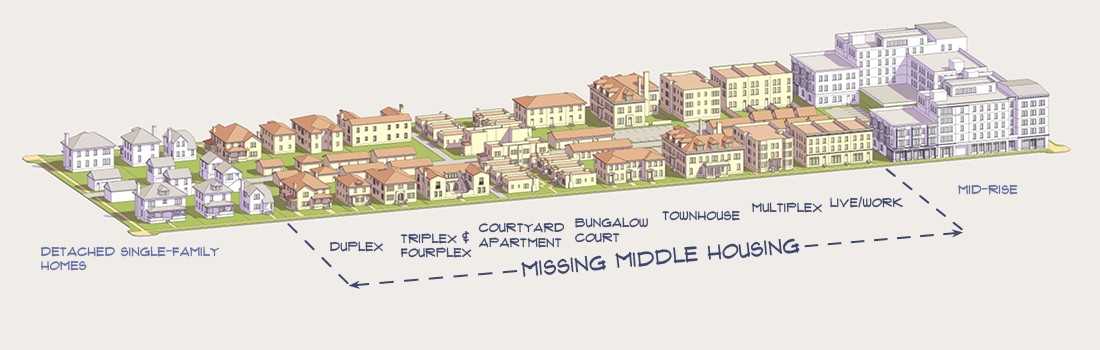

The "missing middle" housing types are those in between (mostly large-lot) single-family detached and large apartment complexes. Berkeley-based architect Dan Parolek coined the term missing middle, accompanied with a diagram, to communicate the housing choices—increasingly in demand today—that are ignored or discouraged by conventional planning and development. These types range from small-lot single family and townhouses, to stacked townhouses and flats, duplexes, triplexes, quadriplexes, courtyard housing of various kinds, and small apartment buildings. Missing middle offers low-rise density, diversity, and forms the backbone of the quintessential American neighborhood.

Public Square editor Robert Steuteville interviews Dan and Karen Parolek, principals of the architecture and urban design firm Opticos Design Inc., and Paddy Steinschnieder, architect and president of Gotham Design & Community Development Ltd., on the subject of missing middle housing.

Why has the term missing middle struck such a chord, and how was it coined?

Dan Parolek: It really caught on like wildfire. We were contacted pretty frequently to either work on it or come talk about it in different places. We created the term in 2013 when we also created the diagram. I think it's given communities, builders, and planners the ability to talk about the need for housing choices in a way that doesn’t use scary terms like density and multi-family, and the other terms that we urban designers, architects, and planners use. It removed a lot of the baggage that comes along with talking about non-single-family housing choices in communities.

Karen Parolek: It addressed housing choices in the context of beloved neighborhoods, particularly the opposition between neighborhood and density. I think missing middle housing has really caught on because it's a way for people to talk about how to keep their neighborhoods and make them better. How do we bring in businesses? How do we provide households to support these businesses without increasing the height and the perceived density of the neighborhood, i.e. making it into a city. Additionally, housing affordability has become a major crisis in the vast majority of walkable cities and towns in the United States, and missing middle housing offers a new solution.

Dan Parolek: It starts with the market for walkable urban living. Chris Nelson's research [Arthur C. Nelson with the University of Arizona] has shown that 90 percent of housing that will be built between now and 2040 would need to be missing middle to meet the demand. Then, there's the shifting household demographics. An estimated shift of 30 percent of all housing will be single-person households. Up to 85 percent of suburban households across the country by 2040 will not have children in them. This creates a discrepancy between what we're providing and what the market wants. We also have a rapidly aging population. The AARP says that 10,000 people a day turn 65. So all of these different aspects converge to a point where people are looking for creative housing solutions.

Steinschneider. It accomplishes a lot of things without effort. First of all, it's the middle. So it's not an extreme, and it's missing, which makes people say, "Well, how can I get what we need?" It responds to so many of the other issues that people want to address in their communities—whether it's walkability, or the density to support different forms of transportation and retail businesses in a downtown. We can have excellent form-based codes that talk about great architecture and design, but it's the feet on the street that's going to make the downtown work and reweave the former urban fabric. But for me, what we're doing is a continuation of the great sprawl experiment started when Harry Truman gave his State of the Union address in 1947. His goal was to promote automobile travel so families could live in the country, but work in the city. This coincided with the invention of the nuclear family, a way that people had never really lived before, but was sold through television and media to the point of becoming a cultural expectation. For 60 years we built for the nuclear family, but it finally ended in 2007 with the recession. You two came in very quickly at that point and said, "Here's what's missing. This is why our communities aren't working. This is why they're not sustainable. If we can reweave those neighborhoods, if we can recreate those place that address the full population, we'll have a much happier, more wonderful place to live.”

Based on this legacy, what obstacles do you face trying to restore the missing middle?

Dan Parolek: Unfortunately, there's a laundry list of obstacles, many of which are still in place and create a need for everybody, regardless of their background or their expertise, to figure out how to overcome them. From 1947 on the federal government laid the framework to enable sprawl. But even today, when we're assessing zoning codes and looking at a city's comprehensive plans, it's amazing how much every city’s zoning code is an obstacle at the most basic level. We’re rewriting the land development code for Austin, Texas and the entire city doesn’t have a single zoning district to actually enable missing middle housing.

Steinschneider: That's amazing. One of the big challenges when dealing with the density is the lack of flexibility regarding a unit. People don’t think of the implications of different types of units. If a developer starts with 10,000 square feet, he can make ten 1,000 square-foot units, one- or two-bedroom apartments, but if he’s told he has to cut it to five units, he still has the same amount of square-footage to sell, so he doesn’t build five 1,000 square-foot units, he builds five 2,000 square-foot ones, which don’t address the original need.

Karen Parolek: Zoning really took off in the 1940s. We were starting to write zoning for this country at the same time that we were building suburbs, so it was primarily effective for auto-oriented places. The reality is that we never learned how to write zoning codes for Missing Middle housing. We never actually bothered to try to write zoning for walkable neighborhoods.

This missing middle is a really appealing concept. But often there is a NIMBY problem with the missing middle. How do you approach that?

Dan Parolek: Whenever I present on this topic, I avoid using the terms density and multi-family. If you enter a conversation with a neighborhood group and start talking about increasing density or adding multi-family, you're not going to win that conversation. But if you show the range of missing middle housing that exists locally or regionally, people tend to be able to personally relate to them. I find this disarms a lot of the opposition and opens people's eyes to accommodating the housing choices that are needed everywhere.

Karen Parolek: It is about reframing the conversation to cover the kind of community its members want and how can we build that kind of community. Oftentimes we'll ask, "Well, do you want to be able to walk to something? Do you want to be able to have a café? Do you want to be able to have a small grocery store?" That means we need enough feet on the street to be able to support that grocery store, and you can't make that work with detached single-family homes. So you need reframe that conversation. “Well, how do we actually make that happen?" In these types of conversations, missing middle housing is a key ingredient to making those visions for what they want work.

Steinschneider: We did an exercise that worked very well in a community where they were not committed to changing zoning codes. They didn't see what was wrong with their old zoning code, but at the same time, they were complaining about the empty stores and raising real estate taxes on the single family homes. They didn't have an industrial base, so they could draw income from elsewhere. We were convinced that the best solution was to revitalize their downtown. Then we gave everyone a disposable camera and we set them loose. We said, "The only thing you have to do is tell us whether you're taking pictures of something you like or something you don't like." Every person who participated took pictures of the downtown retail and shops that were probably built around the 1890s. Everyone said that was something they really liked about the town and they wanted to keep that. We were able to point out that in their 1966 zoning ordinance did not permit this sort of retail, and so that's why it hasn't happened since 1966, even though it was the one thing everyone wanted in their community.

Since there have been these problems with finance and zoning, there's also been a loss of knowledge in the development industry. A couple of generations have passed. So if there is a market, how can developers change their practices to meet this market? And what kind of developers are doing that?

Dan Parolek: Over the last couple of years, builders have prioritized the term attainability. We get calls from builders who historically only deliver single-family, detached housing. Based on increased land cost, increased construction cost, increased fees, increased timing, all of these things, they're starting to find it impossible to deliver the single-family, detached houses, but they're also struggling to deliver the townhouses that are at a price point that the market can absorb. So if they want to explore different types, we work with them to explore integrating missing middle housing into their portfolios. At the other end of the spectrum, you have the multi-family builders who target the percentage of the market that's waiting longer to purchase a house, but are not that interested in living in a conventional garden apartment. Those types of builders are looking at how to integrate Missing Middle housing into their projects to latch on to this market segment that's renting for longer. We're working on a really interesting project right now with an apartment builder in Papillion, Nebraska, just outside of Omaha, to create an entirely new walkable neighborhood that's composed of a range of Missing Middle types. If it's happening in Omaha, Nebraska, it's just a good sign that there's a need for it, and it's likely going to be popping up in a lot of other places across the country.

Steinschneider: [Developer and new urbanist] John Anderson has been trying to cultivate small builders to get involved in their own communities in a way similar to a century ago. In 1890, 1900, a lot of communities evolved because local individuals were the ones building in their community. They understood the community and were trusted as reputable people. The more that we return to that, the better the housing can be because there will be more trust between developers and community. I was running for [local] trustee 20 years ago, and the party that opposed me argued I wasn’t qualified to be in politics because I’m a developer. They thought if you're a developer, you must be sleazy.

Dan Parolek: But if we as new urbanists don't tackle the problem of integrating Missing Middle housing into the portfolios of larger builders and developers, we're never going to achieve the volume that's needed out there. As more and more larger developers reach out to us, it poses a lot of different challenges to do it in a quality way, especially in the context of a walkable neighborhood. New urbanists need to take this to scale to have a true impact.

Karen Parolek: I think we need both scales. The larger developers are able to take on projects in towns and cities that have more land available. We're not going to be building that in San Francisco, there's just not enough land left. But there’s a housing affordability crisis in so many places that quickly getting more residences on the ground is important. Here in California, there will be need for three and a half million more homes in the next ten years, according to a recent study by McKinsey Global Institute. The scale of the problem is gigantic. At a smaller scale, it's important to rebuild trust in our communities. To get good projects that are going to stand the test of time it's going to require small developers who are actually from the community and care about it. At this scale, it’s also important to remove barriers. Zoning reform can change codes to make them simpler and more accessible. For instance, if I decide I want to put an accessory dwelling unit in the back of my house, I can figure out how to do that without having to hire a licensed architect and expensive help to figure out a complicated zoning code. Once the rules become less complicated, it will be easier for people within the community to do small projects. We need to change the system to make it easier for people to build in their own back yard.

Are any kinds of missing middle being built across America, more often now than in recent decades? Where is the trend toward missing middle?

Steinschneider: I look to the infill in the downtowns and the revitalization of existing buildings converted into residential use. In Chicago, we ended up selling a series of lots to developers who could have built tall buildings, but instead they decided on four-story missing middle. It's still pretty good density. It's probably 40 units an acre and it fits the scale of pre-existing Chicago neighborhoods.

Dan Parolek. In the missing middle diagram, it's the types on the left side of the spectrum that I’ve seen. I would classify these as the fee simple where the occupant has ownership of both the unit and the land and the units aren’t stacked. Over the last five to seven years, these are the ones that builders have begun to deliver because they are the closest to what they have historically built and there's a lot less risk inherent in a unit that isn’t part of a condo, especially if you're selling them. The townhouse is a version of this and in some markets, it is not missing. A second type that's caught on is the cottage court or the pocket neighborhood. It still delivers single-family detached houses, but it also delivers a high-quality sense of community that a lot of people are longing for. But it's going to take a little more time and creativity for the builders to get to the point where they're actually stacking units to achieve what I would call the Holy Grail of missing middle: the fourplex that existed in every pre-1940s neighborhood, with two units downstairs and two above. We need to get over the hump and start delivering more of those stacked units within the missing middle spectrum.

Steinschneider: In the early 20th century, even pre-1950s, lots of those houses were very large, but they didn’t just serve the nuclear family. The whole extended family lived in those houses, including grandparents and maybe even aunts and uncles. When I look at that left side of the missing middle housing, I think some of those detached single-family homes, the large McMansions built over the last 60 years, are ripe for that kind of transformation. Recently, we’ve converted a whole slew of big houses that were originally single-family homes into three-, four-, or five-unit buildings. It's only a matter of time before people return to this previous living arrangement as it's one of the ways that we can make viable use of overly large houses.

What are the best tools for a community to build the missing middle?

Dan Parolek: A pilot project is a really good way to provide an example that other builders can refer to and assess its successes. It’s invaluable to have a comp in the market.

Karen Parolek: We've talked to communities about doing a missing middle scan. One of the first things we do is go in and look at the opportunities available to bring missing middle into their communities as well as barriers to entry. With a pilot project or a pretend pilot project, if we were to try to do this, what are the barriers that are going to get in the way, and how do we go about changing those, or working around them? Some of the work on pink zones, especially in Detroit, have begun a dialogue with cities about flexible zoning codes that accommodate test projects.

Steinschneider: Most of the communities I know wait until they feel pressure from their residents about housing. Irvington, New York is not a place that is terribly conducive to social responsibility, but when some families realized that their children graduating from college couldn't afford anything in the town, they started to talk about how they could generate affordable housing. That urgency can come from other sources too. The work of Joe Minicozzi and Chuck Marohn shows that all these single-family houses are loss leaders and they don’t support themselves. Instead of building more single-family houses, these communities can double the tax base on their downtowns by building infill and restoring older buildings to make them useful again as a way to bring down the taxes on the single-family homes.

Karen Parolek: The idea of home ownership and access to home ownership permeates this entire conversation. It's essentially becoming more and more difficult. In a lot of places, you can't even rent a place, much less try and buy a place. But the benefits of home ownership have been proven in raising children, particularly the importance of having a stable home and without having to move constantly. Many equity issues as well as stability for communities start with home ownership, but no one can afford a detached, single-family home. But missing middle housing can change that conversation. What if I can buy a town house instead? What if I can buy a fourplex? I can still buy that with Fanny Mae or Freddy Mac financing, and I can live in one unit, and I can rent out the other three units to make extra income. Or what if we can look at changing some of the regulations, and can we actually make that a four-unit condo building? Then I only have to buy one unit in a four unit building. I don't have to live in a big condo complex, I can live in the neighborhood I want, but I also have access to home ownership and can start to build financial equity a stable home for my children to grow up in. In this regard, missing middle housing is able to contribute a solution to some of the issues facing our country today.

Note: CNU intern Benjamin Crowther helped to produce this interview and article.