Anchors away: Repurposing regional malls to meet new community needs

For the past two decades, the North American retail landscape has been in a transitional state. Shopping preferences have shifted, to increasingly favor place-based destinations with a mix of uses and design elements rooted in traditional urbanism. Simultaneously, the business model that sustained many large-format, brick-and-mortar retail chains has been upended by these changing preferences, by increased competition from online retailers, and by large-scale global economic events.

Specifically, the decline of the department store format has been the subject of much press and discussion over the past decade. The United States Census Bureau defines a department store as an establishment that has, “separate departments for general lines of new merchandise, such as apparel, jewelry, home furnishings, and toys, with no one merchandise line predominating … Department stores may have separate customer checkout areas in each department, central customer checkout areas, or both.”

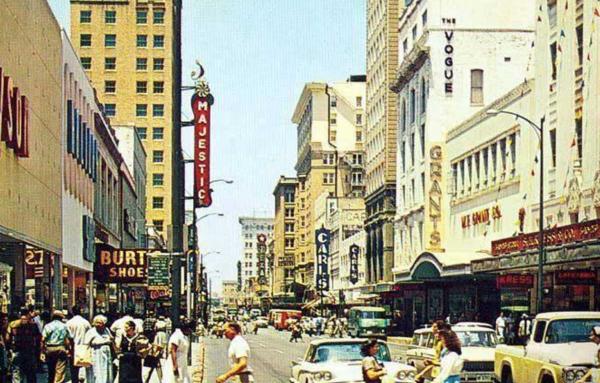

In the second half of the 20th Century, department stores abandoned their ornate main street locations to become “anchor” tenants at new, automobile-oriented shopping malls. The mall business model relied on department store anchors generating up to one-third of the total foot traffic and sales; in exchange, they paid little rent compared to the smaller, “in-line” interior merchants.

The further decline of the mall-anchored department store will bring the threats associated with “graying malls” and “dead malls” to middle-income and upscale suburban communities that may have previously thought themselves immune to the problem. Fortunately, CNU members have been tackling the issue of suburban retrofit for a quarter century, and can claim many successes. A post-COVID economy will demand that this expertise be applied farther and wider than before, and potentially with fewer resources.

The following observations on the future of the department store as a viable retail concept, and the future adaptation, retrofit, and rehabilitation of traditional shopping malls are presented below to supplement this body of knowledge, and to frame the issue in the light of the current economic and public health crisis.

Egad—The department store is dead!

The loss of a local department store is more visible in a community, compared to other types of retail business closures. These closures result in the once-vibrant mall becoming dominated by large, vacant boxes, with the former retailer’s logo reduced to a grimy halo left behind on the building’s brick façade (a “labelscar”). The loss of one anchor store at a regional mall can spur a cascading failure, with other department stores soon following suit. Additionally, in-line tenants have “escape clauses” in their leases, allowing an early termination in the event that an anchor store closes.

The decline of the department store was well underway prior to the current crisis, even in the otherwise strong economy. Once-venerable nameplates like Sears, JC Penney, and Bon-Ton were already undertaking large-scale store closings or complete liquidations during 2018 and 2019. The current macroeconomic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has only accelerated their demise (JC Penney finally sought chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on May 15), and has brought the prospect of store closures or bankruptcy along to upscale brands such as Neiman-Marcus, Lord & Taylor, and Nordstrom.

A prior Public Square article by Sharon Woods, Principal of LandUseUSA Urban Strategies, refuted the notion of a “retail apocalypse” for brick-and-mortar stores, and her assertions still stands—while the pandemic-induced economic downturn will reduce consumer spending and upend development patterns for at least the remainder of this year, shoppers will eventually desire to return, en masse, to the sensory, social experience of physical retail in a traditional urban context. While consumers are growing increasingly comfortable with e-commerce, a solution during an era of quarantine, resilient downtown merchants can adapt and re-emerge in a strong position, in part by recapturing market share lost decades ago to the mall-based retail chains that are now on life support.

The department store is dead—or is it?

While there will be a significant contraction in the footprints of the larger mall-based department store operators, these stores will not vanish entirely. Chains with fewer stores, such as Von Maur and Dillard’s, may well survive with fewer liabilities and benefit from a new vacuum of competition in the segment. Hoping to emulate this advantage, in February Macy's announced a restructuring plan to pare its store count to fewer than 400 locations by 2023 (Macy’s had over 800 locations in 2005).

The remaining department store chains will run leaner, with fewer locations nationwide, but each remaining location will aspire to become a destination: selling a locally-calibrated mix of higher-quality merchandise, and providing experience-based shopping (including unique personal services, on-trend restaurants, and a new attention to the interior design and merchandising of their stores). In a sense, it will be a return to these stores’ roots: they may once again emulate the “palaces of consumption” from which the category originated, albeit in a 21st Century context.

Surviving brands will also have mastered the leveraging of omni-channel marketing, integrating the conveniences of virtual shopping seamlessly with the in-store experience. This will be a marked departure from recent decades, when one anchor department store could barely be differentiated from another in terms of décor and merchandise mix; and all but the most upscale had abandoned any semblance of quality customer service—in-store or online.

The surviving department stores will consolidate their store portfolios in each region, and remain in only the best locations. This may translate to only one to three malls in a large metro area. As the economy stabilizes, they may also eventually open new, smaller stores in downtowns or other walkable districts. This is good news for local independent merchants, as department stores will reprise their anchor roles, directly benefitting smaller shops nearby. However, the few regional malls that do retain department stores will still need to adapt in other ways.

Go to the head of the class

The regional malls that do retain department store branches are those typically categorized as “Class A” or “Class A+” malls. Properties in this category generally achieve over $500-600 in annual sales per square foot of in-line retail space (the highest grossing properties achieve nearly $1000 in sales per square foot—there were fewer than 40 in the US as recently as 2016. These malls have the largest trade areas, and support branded, boutique-style stores that remain popular with shoppers, such as Apple Store, Kate Spade, and Lululemon Athletica. Representative properties include the Somerset Collection near Detroit, Tysons Corner near Washington, D.C., The Galleria in Houston, and Century City in Los Angeles.

Class A and A+ malls had been evolving away from a retail-only model prior to the COVID pandemic, with owners redesigning properties to integrate residential, hospitality, and entertainment components. For example, owner Simon Property Group built high-end apartments and hotels on the periphery of The Galleria in the years following the Great Recession, on land previously used for parking. In another example, Taubman Company’s monolithic, windowless Beverly Center in Los Angeles underwent major renovations beginning in 2016, adding skylights, exterior windows, and street-facing storefronts to partially “turn its insides out.”

These modifications come at great expense, and the owners of Class A and A+ malls will likely shy away from similar major investments in the near term. When the global economy stabilizes and a denouement to the COVID threat occurs, Class A and A+ properties will be the few holdouts that retain department stores, but as only one component of an experience-based, mixed-use, destination.

Mall retrofit in the post-COVID world

The majority of malls, both in metro areas and smaller communities, will undoubtedly see the exodus of department store anchors accelerate due to the COVID crisis. In the previous decade, a relatively strong economy allowed some owners to redevelop failing properties as mixed-use urban places, re-use anchor store boxes as office space, or create new-build housing and entertainment options.

Unfortunately, the economic slowdown is likely to put planned redevelopment and re-use projects on hold indefinitely, while making such options infeasible elsewhere. While there has been a great deal of prognostication about the ultimate societal impact of the COVID pandemic, it remains unclear if major shifts in our daily behaviors will be temporary or permanent.

For example, will corporate tenants move to reduce overall consumption of office space as workers acclimate to teleworking? Perhaps a counterargument could be made that some might seek to increase floor space to capitalize on the benefits of in-person collaboration, while providing employees with flexible working space that gives them adequate social distance from their peers. The latter scenario would bode well for low cost re-purposing of anchor store boxes.

COVID’s impact on supply chains is also leading to a reassessment of the demand for warehousing and distribution space, including an expanded need for increased capacity of temperature-controlled space for perishable food items. Existing facilities will consider expanding, to give workers more space with greater distance. As of 2019, at least 24 dark retail properties had been redeveloped to serve the supply chain industry. Sited along major corridors and surrounded by asphalt, repurposed shopping malls fit the requirements for both highway access and physical space demanded by the industry.

The pandemic has also placed health and wellness in a new light. It should be anticipated that demand for fitness-oriented recreation will increase, and indeed, gyms, health clubs, and fitness studios have been welcomed as replacements for department store anchors in recent years. This trend will continue, contingent upon the fitness industry’s ability to implement design solutions and sanitation protocols that elicit confidence on the part of potential customers.

In the same vein, healthcare companies could repurpose anchor store boxes as adjunct space for community clinics, testing, and hopefully, vaccinations. Larger than a community clinic or urgent care center, but smaller than a traditional hospital, anchor store buildings could be designed for quick reconfiguration as temporary hospital space if regional demand becomes stretched.

Long-term care: The long-term solution?

The way we care for our seniors—one of the population segments most vulnerable to the COVID virus—is also being scrutinized, and protecting them will require new building designs and care protocols. Though data are still incomplete, it is currently estimated that at least one-third of US COVID deaths are of workers or residents at long-term senior care facilities. The need for replacement of many outdated facilities is becoming apparent, and could be a promising repurpose for flagging indoor malls.

Architecture firm Perkins Eastman recently articulated 13 design guidelines for pandemic-resistant long-term care facilities; these guidelines could be incorporated into a repurposed indoor regional shopping center. Examples include:

- Secure perimeters—Here is one instance where the siting of the shopping mall, typically in a large parking lot ringed by an access road, could actually be advantageous.

- Many separate entry points, customized for various users, each with space to conduct screening protocols—A typical mall with three anchor stores contains at least 15 major points of ingress/egress.

- Private rooms or apartments for all facility residents, which would allow them to shelter-in-place as needed—Larger apartments could be fitted into former in-line store space, at ground level and with direct outdoor access; units for those requiring greater care could be configured in a anchor store box with new fenestration.

- Specific area devoted to on-site medical care that can accommodate isolated patients in times of stress on the regional medical system; and residential units for use by facility staff on a temporary basis, in times of health crisis—Anchor store boxes have the flexibility to be converted into separate spaces for these and other elements.

- Safe access to ample, secure outdoor spaces for recreation—With a lower parking demand, much of the surrounding asphalt could be repurposed as green space for residents; this space could be directly accessed from ground level apartments.

While such a retrofit of a shopping center could be costly (for example, HVAC systems may need to be completely reworked), it would be far less taxing on any given community’s built form and supporting infrastructure than developing a facility with these large and unique spatial requirements from scratch. It further responds to a demonstrated need in the marketplace untethered to conventional commercial uses, especially in markets where the repurposing of malls for such uses was questionable in a strong economy.

A silver lining

The mall-anchored, full-service department store spread across thousands of locations was failing as a retail format prior to the pandemic, whose arrival only sped up the process. As the economy eventually stabilizes, the department store concept will nevertheless survive, ultimately reinventing itself as an experience-oriented destination with relatively few outlets per region.

The hundreds of malls that will lose their department store anchors will likely not be able to finance substantial redevelopment efforts. Some of them will survive by attracting fitness centers, grocery stores, and occasionally, retail concepts previously absent from a mall context such as IKEA or e-commerce retailers. For the rest of them, community stakeholders—including property owners, financial institutions, and local governments—must work together to allow for creatively repurposing these properties to non-retail uses.

A silver lining to the pandemic is that new demand is being created for redesigned spaces in which we can safely store our food, provide housing for our elderly, administer medical care, and work together in-person. The design parameters of the purpose-built shopping mall can perhaps, at long last, be exploited to meet these new challenges.