Problems and solutions for main street retail

Note: This is one of a series of ongoing Public Square articles on the market, technological, and cultural transformation of the $5 trillion retail industry—and how it relates to a continued shift toward walkable, urban living.

People love a main street, but the tired, dated look and incomplete tenant mix of many smaller downtowns—along with car-oriented streets—are a deterrent to revitalization. Small-to-midsize downtowns represent some of the best opportunities and biggest challenges for urban retail in the next decade.

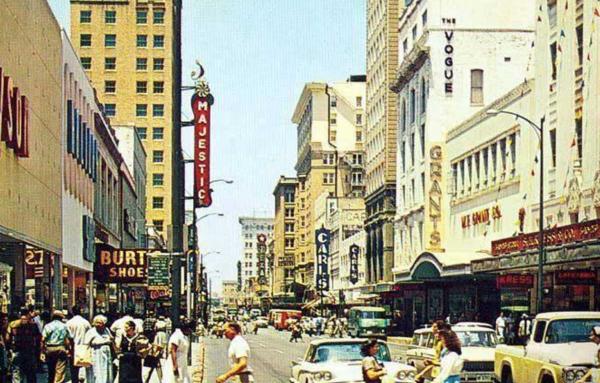

Up to the 1950s, most Americans shopped, and sought services and entertainment in downtowns—large and small. Then a succession of strip malls, indoor malls, and big box stores captured most customers. Many middle-class households moved to the suburbs and suburban malls benefited from a coordinated tenant mix and management that downtowns lacked. The main streets and downtowns lost up to 90 percent of their business in the latter half of the 20th Century.

A return to urban living means that downtowns have an opportunity to regain some of their market share notes Gibbs Planning Group, which recently conducted “shopability” studies for two downtowns in Florida. Nowadays, customers seek the authenticity of a main street, yet are used to the quality standards of a suburban center. “The cohesive management of the shopping center is now expected by the downtown shopper and it is the duty of the downtown and the city to determine how best to deliver this level of service,” notes Gibbs.

Lessons of this research could be applied to many main streets and small downtowns.

New Port Richey, population 16,000, is one of hundreds of towns with a traditional main street with significant potential. Like many main streets, New Port Richey’s downtown has suffered neglect and disinvestment in the age of automobile-oriented retail. Nevertheless, “The downtown also has a strong market,” according to Gibbs. “Its trade area can support up to an additional 169,000 square feet of retail and restaurant development.”

Delray Beach, population 70,000, has a larger, more modern downtown, with significant national retail—and it has already revitalized substantially since 2000. “By understanding and implementing best practices of the retail and real estate development industries while enforcing many reasonable existing regulations, Delray Beach can continue its growth and refinement in a measured and market-driven approach,” Gibbs says.

Storefronts

Nearly all of the New Port Richey’s storefronts have problems, according to Gibbs. “Overall, the downtown’s storefronts lack the design character necessary for a competitive shopping district.” Windows, signage, awnings, blank walls, lettering in windows—all are problems in New Port Richey, and they impact the main street experience. A number of the stores have reflective glass and block glass windows, preventing passersby from looking in the store. “Shoppers feel unsafe entering a business that they cannot see inside. Dark-tinted, mirrored, and glass block windows limit the opportunity for window shopping and pedestrians are known to walk faster along storefronts where these are installed,” the report says.

Gibbs details some storefront concerns that are little known—for example, large lettering on a storefront sends a negative message. “Research has shown that there is an inverse relationship between the size of lettering on a storefront and the perceived value of the goods inside,” Gibbs reports, noting that some New Port Richey retailers have large window lettering. “Smaller font leads customers to believe that they are going to receive excellent service, unique products and a good value.”

Some stores have vacant or painted-over signbands—a horizontal space at the top of the storefront—and this is a problem even when other signage is available. “Signbands are an integral component of a desirable storefront and a blank signband suggests a business is temporary while detracting from the streetscape,” the report says.

Although the storefronts are generally higher quality in Delray Beach, the report identified problems, such as some businesses with inoperable front doors, suggesting “the pedestrian is not welcome and may even signal that a business is closed—at best it makes for an awkward first entry attempt for the ambitious visitor. Ground-floor businesses should be required to have an operable primary entry along the prominent streets and store layout and display should reinforce the use of this primary entrance.”

Gibbs also criticized downtown shops with “standard aluminum storefronts,” which are more appropriate for suburban strip malls. “A cheap storefront suggests to the customer the business offers lesser quality and generic goods and services. ... At a minimum, aluminum storefronts should be powder coated with a dark color that accentuates the window merchandising.”

Dated and tattered awnings are another area of concern for both cities.

Parking

The primary goal of parking management is to ensure the shopper is able to find convenient parking near their destination,” Gibbs writes.

“A well-calibrated parking plan will leave approximately 10 percent of on-street stalls available with turnover of 15 to 20 times per day, while off-street or garage parking should always be readily available with turnover of three to five times per day.”

The city should continually monitor on-street parking to make sure that a few spaces are available—and the cost is calibrated to encourage availability. “The most desirable or often-filled space should charge at least double the cost fo less convenient spaces,” the report says.

Many towns and small cities are now installing parking kiosks, but Gibbs suggests this is a mistake. Instead, the firm recommends old-style, coin-operated meters that now accept credit cards and mobile payments. These meters are less complicated and preferred by downtown shoppers, the firm writes. Kiosks lengthen the time required for payment, the firm states. “The whole experience can be frustrating to many shoppers, exaggerating their perception of difficult-to-use or inconvenient parking.”

In addition, more frugal or long-term shoppers should be given an opportunity park in more remote locations like parking garages. These garages should be free for the first two hours, or at least very inexpensive, the firm writes.

National retailers

Up until World War II, national retailers existed only in downtowns. Now, many cities discourage national retailers because of concerns that they detract from local character. Gibbs suggest that cities might want to rethink their attitudes. “National retailers with their highly focused research, planning, management, and marketing strategies can serve as anchors or draws for the downtown and expose more consumers to local shops,” the firm writes of in the Delray report. “These standards and strategies may also ‘raise-the-bar’ in terms of shopper expectations and promote healthy competition and cross-shopping within the district.”

However, the firm recommends that cities ensure that national retailers meet the highest standards for design, while maintaining the general exterior design of the original building.

The optimal tenant mix is evenly split between national, regional, and local stores—with one-third share going to each. Cities can help to maintain the local share by dedicating increased property values, sales, and permit fees from national retailers to short-term rental assistance, technical assistance, and façade improvements for local retailers.

Liner buildings and underutilized sites

Some downtowns, New Port Richey is an example, benefit most from reuse of existing buildings. Downtowns like Delray Beach are ready for new development. Many large lots downtown feature set-back buildings and could benefit from liner buildings, which can be as shallow as 15 to 25 feet and “can deploy ground-floor uses to the street frontage and un-tap previously unrealized real estate value,” Gibbs writes.

Small liner buildings allow the existing uses to maintain their operation and visibility while supplying desirable locations for local and small national retailers and increasing the vibrancy of the street life, the firm reports.

Also, Delray Beach has large and contiguous parcels that represent some of the most desirable and development ready property in the region. “The City should host a developer’s workshop to determine the existing hurdles to realizing development on these sites and the highest and best use for the properties,” Gibbs reports.

Walkable streets

Both cities suffer from streets that have been made less comfortable for pedestrians and bicyclists over the years. Delray Beach has streets with right-turn (deceleration) lanes, which Gibbs says are not appropriate to an urban context. “The additional lane extends the distance to cross a street by 10- to 12-feet and pedestrians must contend with cars attempting to turn right during a red light. … deceleration lanes generally extend a full block, removing the potential on-street parking that could be in its place.”

The firm recommends a road diet for a section of Grand Boulevard in New Port Richey—one of the downtown's two primary streets. “There is sufficient room to re-stripe this section of the boulevard to allow for two ten-foot travel lanes and two eight-foot parking lanes on both sides of the street.”

Lack of clean and well-maintained sidewalks are a problem in both cities. “Top retail destinations, public and private, power wash sidewalks and other public surfaces on a weekly basis or more if necessary. Whether it is the responsibility of the individual business owners or a central management authority, pedestrian spaces should be clean and regularly maintained.”

Directional signage

Many cities need help with directional signage, which should have a consistent and clear design, and direct drivers from main roads to downtown and also to parking. Both Delray Beach and New Port Richey lack clear and consistent signage, suggesting this is a common problem and opportunity for small downtowns.

Many main streets have shortcomings that prevent them from realizing their potential. Suburbs are losing retail tenants, but this loss could be a gain for downtowns that upgrade their aesthetics and infrastructure. “While shopping centers are still a viable land use, a renewed interest in urban living, working, shopping and dining, has positioned downtowns … to reclaim market share and attract the amenities and development to improve the quality of life for the community,” Gibbs notes.