Defining the 15-minute city

See the more recent, second essay, by Andres Duany and Robert Steuteville on the 15-minute city. These essays are complementary.

The 15-minute city is gaining significant traction politically and in planning circles, but what does it mean? Definitions vary, and there is so much slack in the concept—depending on what transportation modes are included—that even conventional suburban sprawl might qualify under some circumstances.

The term offers a two-fold opportunity for urbanists. First, the 15-minute city is a simple enough concept that it resonates with a wide range of people. It was used as a cornerstone of Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s successful reelection in Paris, France, in 2020, and lately former HUD secretary Shaun Donovan has adopted the concept as a key to his New York City mayoral candidacy. Urbanists have an urgent opportunity to help define the 15-minute city, and what it means to sustainable planning and urban design, before it is discredited as a mere political slogan.

Second, the concept can add substantively to the practice of urbanism because it deals with a neglected scale of planning that is larger than the neighborhood, but smaller than the metropolitan region. It shows planners where to locate facilities that serve multiple neighborhoods. It employs conceptual radii drawn on plans in a similar way to urbanists’ familiar quarter-mile “pedestrian shed.”

The “15-minute city” may be defined as an ideal geography where most human needs and many desires are located within a travel distance of 15 minutes. While automobiles may be accommodated in the 15-minute city, they cannot determine its scale or urban form. Based on automobile travel, most metropolitan areas may be 15-minute cities.

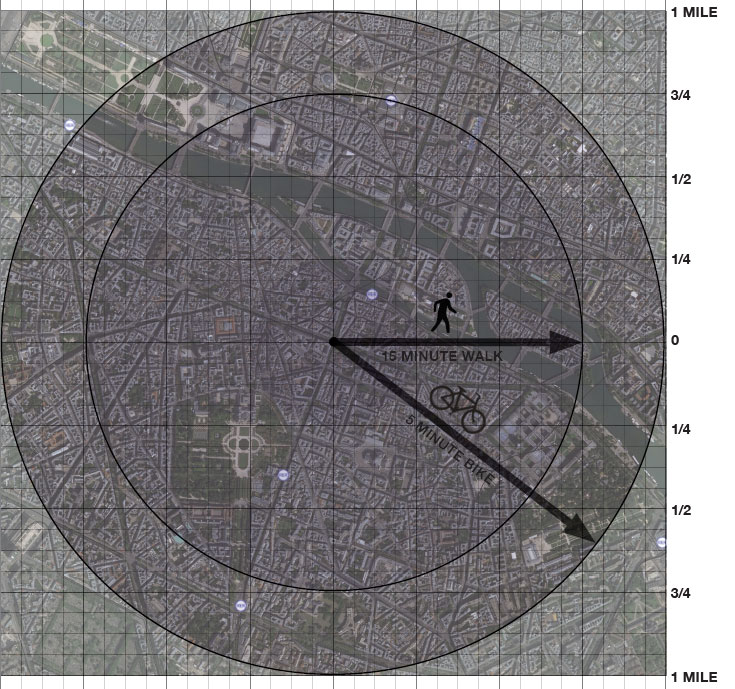

Instead, the 15-minute city is defined by its ability to provide access to all human needs by walking or bicycling for a quarter hour or less. Transit should be provided within the 15-minute city, but cannot accurately define its scale—for reasons that will be explained later.

Confusingly, some cities use the term “15-minute neighborhood” instead of “15-minute city,” and the two phrases are similar in general intention—but “city” is more accurate. The area implied inside the walking and biking sheds is much larger than a single neighborhood.

Implications and attainability

Most urban areas built prior to the overwhelming proliferation of cars have the structure of a 15-minute city—so restoring the goal may be relatively easy, depending on how much damage was done due to urban renewal, in-city highways, disinvestment, and loss of population. For more recent cities and suburban areas, the task will be more difficult—as cars aren’t subject to spatial discipline. When an urban area achieves the 15-minute city goal by organic evolution or legal inducement, several positive implications follow:

- It is socioeconomically equitable—those without a car could easily access all their needs. This requirement would be a logical extension of current building accessibility requirements.

- The area is small enough that measuring diversity, in balance, produces a useful indicator. In larger geographic areas, diversity has less meaning because many human needs could be too distant to be easily accessible anyway.

- The need for transportation is minimized—and therefore the reduction in fuel mitigates global warming.

- Human-powered transportation, which improves health and well-being, is promoted. The benefits are greater than one compact neighborhood alone could provide.

- The convenient location of services, accessible by multiple modes, saves time and improves quality of life.

The 15-minute city is a slippery ideal depending on:

- The list of needs and desires to be provided within the shed (e.g., ranging from an elementary school or a clinic to a university or a hospital.)

- The means of transport, which will determine the size of the shed.

- What is assumed to be the average housing density, which determines the population within the shed that is able to support services.

Levels of sheds

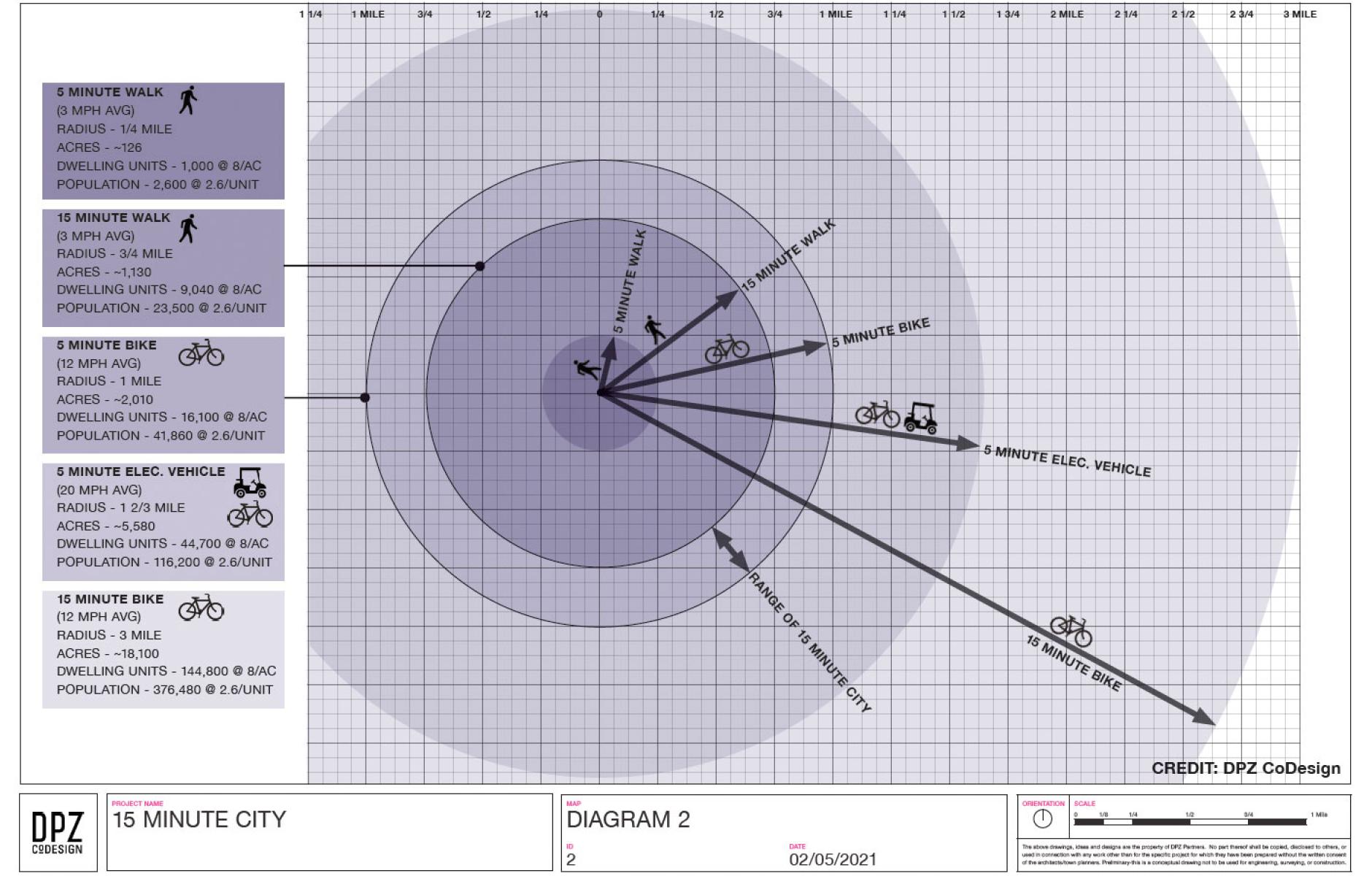

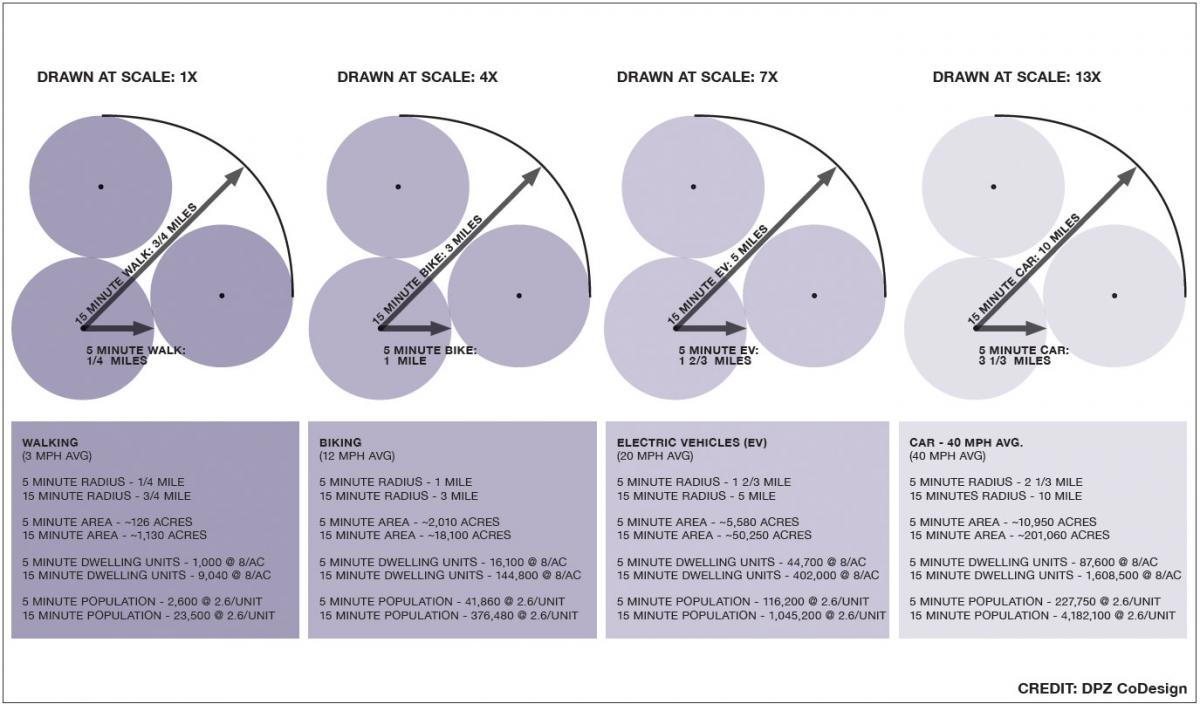

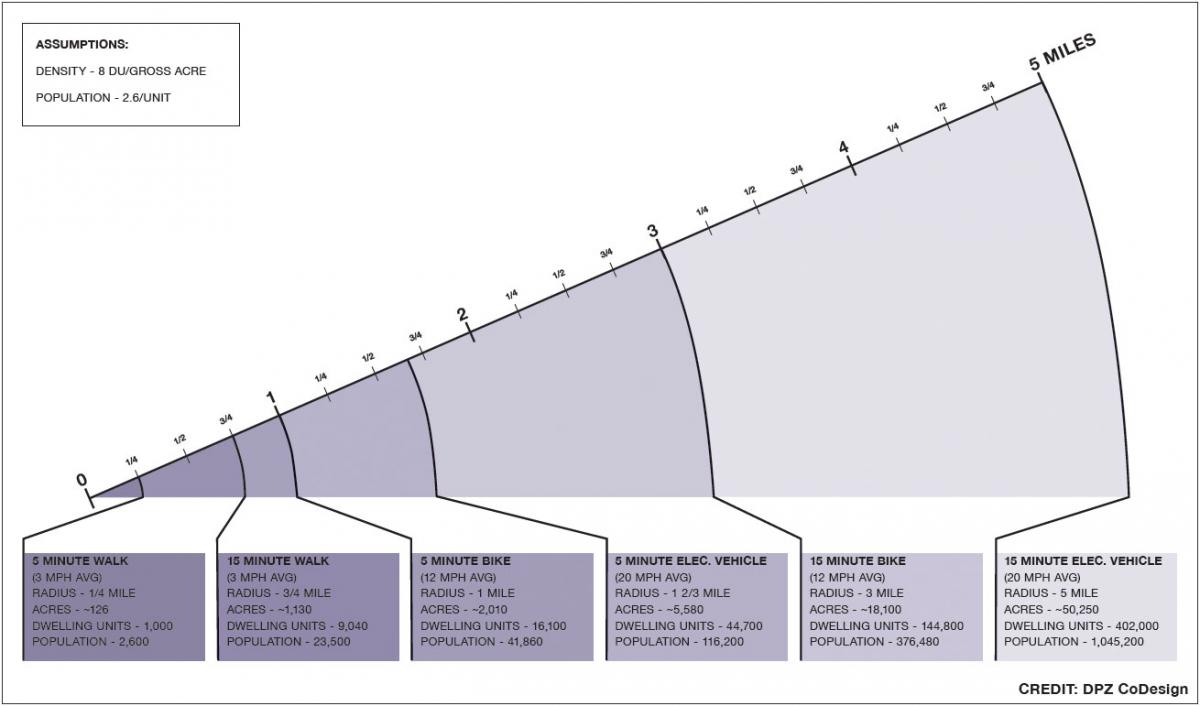

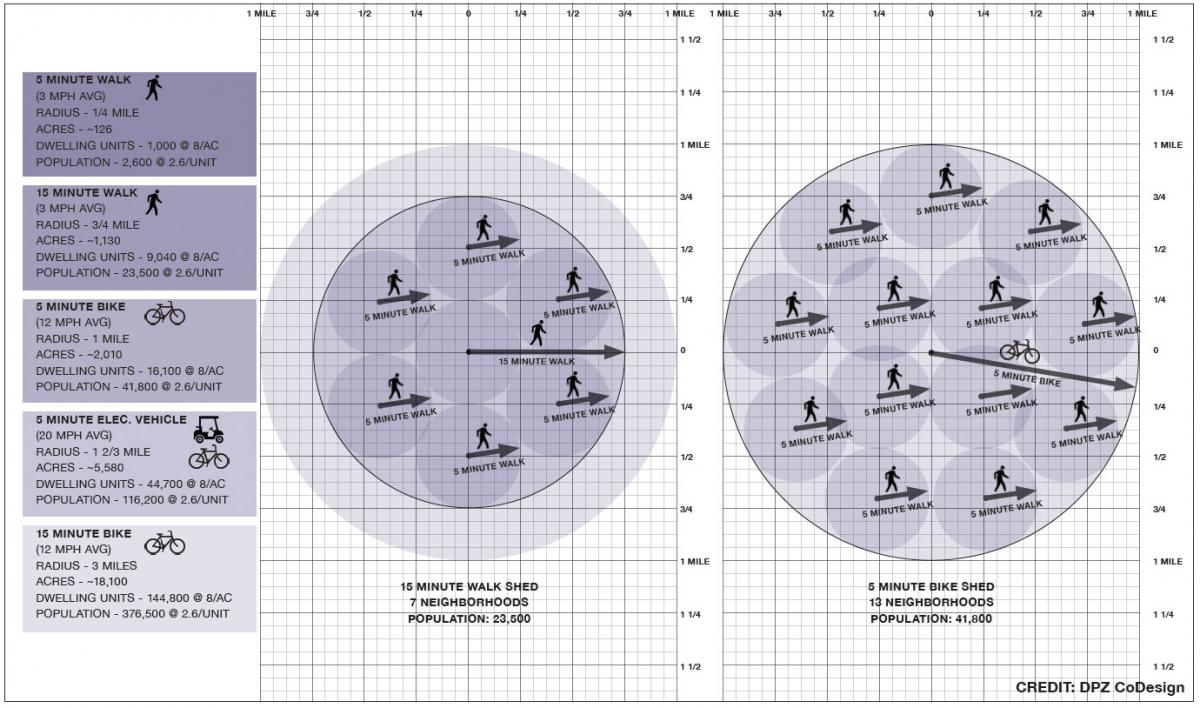

New urbanists have always focused on the average 5-minute walk as the scale of one neighborhood. New urban plans are identified by their quarter-mile circles, which show notional centers and edges of mixed-use neighborhoods. The 5-minute walk remains important but requires the 15-minute city comprised of several neighborhoods nested together, coalescing at a scale that is able to meet all of people’s daily and weekly needs.

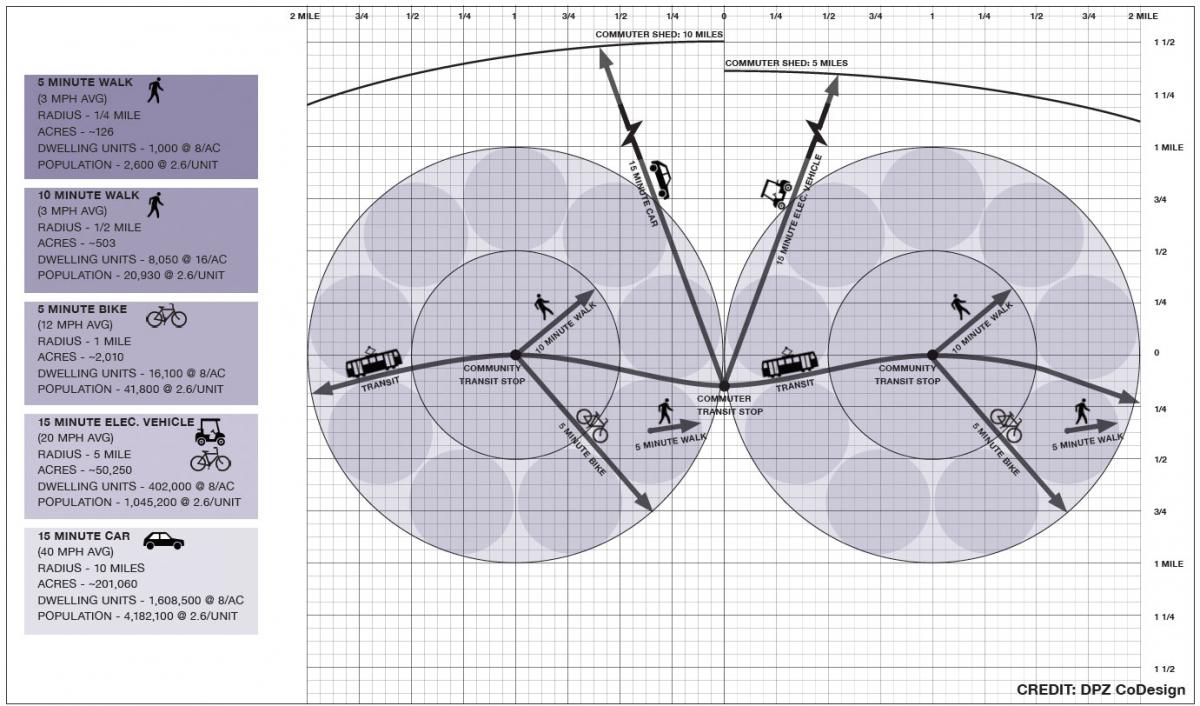

The 15-minute city implies three levels of sheds. Within each of these sheds, a gross density of at least eight living spaces an acre may be assumed, including open space, civic facilities, and a variety of housing such as single homes, townhouses, and multifamily. That’s approximately the overall density of traditional cities like Philadelphia and Washington, DC, which consist of mostly low-rise neighborhoods with a full range of housing types. At a lower density, services will be more spread out and/or smaller in scale.

The three shed levels are:

- The 5-minute walk shed, a quarter-mile from center to edge, indicating the individual neighborhood. Each quarter-mile shed must have ordinary daily needs, a range of housing types, and a center (generally a public square or main street with minimal mixed use). Small businesses, at least, are located in the neighborhood. The population may be provisionally calculated at 2,600.

- A 15-minute walk shed, three-quarters of a mile from center to edge, is the maximum distance that most people are going to walk. Within this shed should be located a full mix of uses, including a grocery store, pharmacy, general merchandise, and public schools. Larger parks that serve multiple neighborhoods will be found here, in addition to larger employers—but not necessarily the region’s biggest. The 15-minute walk shed provides access to regional transit—at least one station. This shed is similar in size to a 5-minute bicycle shed, and the bicycle can be used to transport purchased goods. The shed provides for weekly and daily needs. The population is approximately 23,000.

- The 15-minute bicycle shed would give access to major cultural, medical, and higher education facilities. Regional parks and major employers can be found here. Access to intercity transit may be available. This shed provides access to special needs. The total extent of the 15-minute city is therefore defined by the three-mile radius of the 15-minute bike ride. The population may be calculated at 350,000.

These standards listed above are minimums. Some neighborhoods, depending on the urban-to-rural Transect zone mix, might achieve higher densities. Residents of a downtown core, for example, might have many of the higher-level amenities and services in their five-minute walk shed.

Beyond density, a walkable urban fabric is necessary to make the 15-minute city work. That implies a connected network of thoroughfares (streets, passages, paths) and small blocks knitting together the neighborhoods. A 15-minute walk encompasses seven typical neighborhoods. The 5-minute bike ride, slightly bigger, can include as many as 13.

Shadows and other impediments

There are bound to be problem areas within the 15-minute city. The street network will have interruptions and places of discontinuity. “Pedestrian shadows”—pockets of lower walkability—will mar the pedestrian experience. “Shadows” may be created by facilities such as large schoolyards and industrial sites with inactive building frontages.

Almost certainly the shed will include at least one major barrier, such as an arterial thoroughfare. These barriers often produce what Jane Jacobs called “border vacuums”—stunted urban life on the adjacent blocks. Barriers can reduce the effective size of the shed and impact the services available within the 15-minute city.

In some cases, planners can do something about these problems. An arterial thoroughfare can be redesigned—or partly redesigned—to provide access to vital services on the other side. Zoning can change and parking lots redeveloped to reduce border vacuums. Keep in mind, however, that imperfections can serve a purpose. A less valuable area could be an opportunity for lower rents and gritty attractions like a nightclub that may be inappropriate elsewhere in the 15-minute city.

Transit and the 15-minute city

Some jurisdictions include transit in their definition of the 15-minute city. Boulder, Colorado, for example, notes that “In a 15-minute neighborhood, people can access their basic needs (parks, food, etc.) within 15 minutes of walking, biking, or transit.” Transit service is one of the human needs that should be fulfilled in the 15-minute city, but using it to define the concept presents serious difficulties. An individual riding transit needs to walk to the station, wait for the train or bus, ride the train or bus, then walk to the final destination. That trip will be different for every location and destination and will depend on a level of service that changes. How far a person can get in 15 minutes using transit depends on too many variables to provide the discipline of a shed. Walking and biking don’t depend on these variables and are essentially door to door. Although transit must be promoted in the 15-minute city, including transit in the definition makes for an apples-to-oranges comparison that introduces excessive slack into the concept.

Two kinds of stations may be incorporated into the 15-minute city—community transit stops, which are primarily accessed through human-powered mobility, and commuter transit stops, which are accessed by car. The community stop should be at the center of the 15-minute city and the commuter stop may go at the edge, perhaps where two 15-minute city areas abut. The transit stations connect the 15-minute city sectors and allow access to transit from more distant locations.

Another argument could be made to use the range of electric bikes and neighborhood electric vehicles (a.k.a. golf carts) to define the geographic area of the 15-minute city. Small electric vehicles are an inexpensive and practical transportation mode with a future and should be accommodated. However, these vehicles may average 20 mph—generating a five-mile radius or nearly 80 square miles. Planning for diversity within such a shed would have no meaning because of the aforementioned slack. Such electric vehicles should not determine the scale of the 15-minute city—while they should be encouraged as a good way to get around.

Quality of the walk

The 15-minute city is not just defined by the ability to walk or bike for 15 minutes, but also by the quality of the pedestrian experience—which architect Steve Mouzon refers to as “Walk Appeal.” With high Walk Appeal and truly attractive and useful destinations, people are likely to walk longer distances. If Walk Appeal is low, most people will tend to get into their cars. While driving is inevitably an option, for health and environmental reasons it should not be the default choice.

The 15-minute city may now be capturing media attention, but it has a long history. The term has been “common in the transportation accessibility world for decades,” notes Wes Marshall, professor of civil engineering at University of Colorado, Denver.1

Moreover, the concept has been refined by new urbanist ideas like the quarter-mile pedestrian shed, the half-mile transit shed, and the bicycle shed as defined in the SmartCode. Urban theorists such as Eliel Saarinen, Leon Krier, Peter Calthorpe, Jan Gehl, and Christopher Alexander have long established pedestrian sheds as a principle of the compact city.

The 5-minute neighborhood is integral to the 15-minute city. When multiple neighborhoods are combined in a 15-minute walk shed and 5-minute bicycle shed, the concept of the human scale becomes all that more precise and powerful while remaining conceptually similar enough for public support.

The 15-minute city is an influential idea because it relates the walkable city to all who live according to the metric of time.2 Everyone can imagine the benefits of having all of their needs available by means of human locomotion. This takes planning and transportation down to the personal, and hence the political, level.

Urbanists can salvage the 15-minute city from its destiny as a cliché if it is defined clearly, with flexibility, but without too much slack. So defined, it becomes a tool that activates the array of principles that promote livable, healthy, sustainable societies.

NOTE—On the question of the precision implied by the convention of these circles:

- This is a graphic illustration to clarify the relative size of each shed.

- The numerical calculations are averages. Some will live much closer to certain destinations, while others willingly travel much further than the outer limit of the presumed radius.

- Urban trajectories are not centroidal as implied by the arrows, but along rectangular blocks. That discrepancy is within parameters of the calculations.

- There are destinations that do not coincide with the graphic centroid. Time corrects this. The older organic evolution and newer technocratic protocols will ensure that destinations are both rationally dispersed and symbiotically grouped at centers.

- Metrics of this kind are deployed by the specialized interests that decide the pattern of human settlement: the national retailers with their locational protocols, the school boards projecting classroom capacity, the traffic engineers calculating traffic capacity, companies who project water, sewer, trash, and electrical infrastructure, bureaucracies organizing municipal services. These professional silos have credibility in the public debates. Why should urban designers be the sole exception? Designers, being subjective, devolve to others the design of the city—much to its detriment.

ASSUMING a deviation of plus or minus 20 percent will approach a local condition while still reflecting the general principles.

1 January 25, 2021, email to Robert Steuteville from Wes Marshall.

2 This point, using the phrase "everyone lives their lives through the metric of time," was made by Kit Krankel McCullough, lecturer in architecture at the University of Michigan, in a comment on Public Square.

Read the second essay on the 15-minute City by Andres Duany and Robert Steuteville