The 15-minute city is the new 5-minute walk

Why is the 15-minute city important? The 15-minute city is to the 21st Century what the 5-minute walk was to the 19th and early 20th centuries. I realized this after reading a history of my neighborhood, Fall Creek in Ithaca, New York.

Because the neighborhood hasn’t physically changed that much since the 19th Century—it has the same street layout, most of the same buildings, and is still highly walkable—I assumed that the neighborhood functioned in a similar way to how it functioned back then.

Like many places built prior to 1950, it is built on the scale of about a quarter mile from center to edge—approximately a five-minute walk. Fall Creek contains a mix of uses—there are restaurants, a coffee shop, a tavern, a pharmacy, churches, and an elementary school (where both of my children attended, and they never took a bus). The population and scale of buildings are similar to the early 20th Century.

Culturally, my neighborhood is an innovator. It was the birthplace of Porchfest in 2007, where local musicians play for free on porches, stoops, and front yards one day a year (see photo at top). Beginning with 20-plus musicians the first year, the event grew steadily and the most recent Ithaca Porchfest (2019) had about 170 acts. Porchfest has spread around the US, and now there are more than 100 similar events in US cities (and some in Canada also).

Fall Creek residents also can walk downtown, where there is a greater variety of culture and jobs. In short, Fall Creek is a classic traditional neighborhood. Nevertheless, it is a far cry from what it was 100 years ago in terms of access to jobs and services. Fall Creek does not function the same today as it did then.

The name Fall Creek comes from the stream that forms its northern boundary, including a 140-foot waterfall, Ithaca Falls, at the edge of the neighborhood. The southern and western boundaries of the neighborhood are formed by Cascadilla Creek, which also has falls.

Mostly powered by the falls, the neighborhood had an amazing variety of industry, including a distillery, several gristmills (including one processing 40,000 bushels of wheat a year), a plaster mill using regionally sourced gypsum, an oil producer using vegetables as raw material, a paper mill that made a variety of products including Ithaca Gray Rag sold nationally, a wool cloth mill, a sawmill, an iron foundry, a rake factory, a tub and firkin factory (firkin is a small cask—the facility also produced pails), a farm equipment producer, a hub-and-spoke factory, a clock factory, a pottery, a wind instrument maker, and the Ithaca Gun Company, which sold high-quality shotguns and other firearms.

Our neighborhood not only produced for local needs, but exported goods nationally and internationally—including guns, rakes, clocks, and paper. Every once in a while, on Antiques Roadshow, someone brings in an Ithaca Calendar Clock—they keep the date and time and even adjust automatically for leap year. They are works of manufacturing art—as are Ithaca shotguns, one of them once owned by Annie Oakley.

The 19th Century Fall Creek census recorded coopers, tailors, shoemakers, cigar makers and sellers, blacksmiths, carpenters, clerks, and grocers. Small grocers were scattered throughout the neighborhood from the 19th Century to well into the second half of the 20th Century. These grocers—often referred to as corner stores—were particularly abundant in the 1930s and 1940s, according to the history written by local librarian Amy Humber, in a book called Ithaca’s Neighborhoods: the Rhine, the Hill, and the Goose Pasture. The last neighborhood grocer went out of business in 1980. In simpler times, residents could get all of their daily and most of their weekly needs within a two-or-three-minute walk of every house, so plentiful were these stores throughout the neighborhood. “Eventually, the small groceries were unable to compete with the supermarkets,” writes Humber—and all disappeared in the three decades after 1950.

There was a sanatorium, a 15-bed health care facility, a couple of blocks from my house—and so health care workers were part of the mix, and doctors made house calls. There were hotels and inns, including the Fall Creek House, a tavern that has been continually operating since the 1850s. There was a fire company that operated from the middle of the 19th Century to the 1990s—in what is now a single-family house.

In short, nearly everything a resident would need, including access to all kinds of employment, was located right in Fall Creek—within a five-minute walk. Downtown was within a five-minute bike, carriage, or trolley ride to reach larger stores and regional facilities.

Given how our economy and needs have changed, I’d venture to say there is no US neighborhood now that is as self-sufficient as Fall Creek was a hundred or 150 years ago. Today, we cannot provide the robust economic variety that was routinely available within a 5-or-10-minute walk prior to 1950.

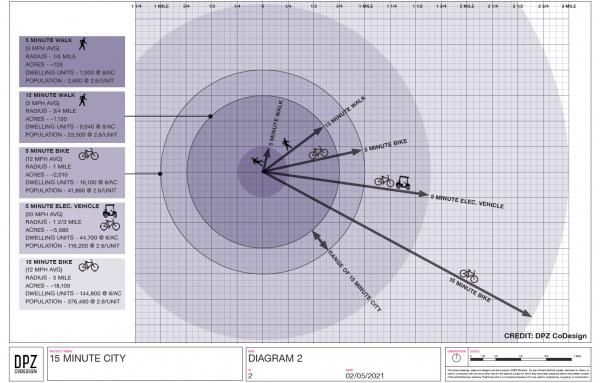

But we can still do this in what is called the 15-minute city. The “15-minute city” may be defined as an ideal geography where most human needs and many desires are located within a travel distance of 15 minutes. While automobiles may be accommodated in the 15-minute city, they cannot determine its scale or urban form. Instead, the scale and form are determined by the distance you can travel in 15 minutes by walking or biking.

Until recently, new urbanists focused on the 5-minute walk as the basis for building human-scale communities. The movement looked to traditional neighborhoods like Fall Creek as models of sustainable and livable places. The 5-minute walk is still an important measure, because it is based on the human body. And yet the economy and culture have radically changed in the last century. While individual neighborhoods can still provide for some needs, people typically must go much further to satisfy most needs and desires and reach employment.

The 5-minute walk shed—the typical neighborhood—is about 125 acres. When you expand that pedestrian shed to 15 minutes, the area is 1,130 acres, or 1.75 square miles. The 15-minute bicycle shed is huge—18,000 acres or 28 square miles. The area within that shed is mostly walkable in an ideal 15-minute city, with a continuous fabric of streets and small blocks.

The 15-minute city should include a wide variety of jobs, culture, and services—including government, health care, shopping, parks, and education, covering most of what people need day-to-day and week-to-week. Although it covers a much larger area, the 15-minute city is still a human-scale measurement. If we can walk or bike some place in a quarter hour, it still feels accessible. We don’t really need a car—or at least the car is optional for many trips.

Today, Ithaca is more of a 15-minute city than a 5-minute place. Not counting those who work at home (and there are many), there is very little employment in my neighborhood. I feel very fortunate that I can buy some things within a 5-minute walk, but significant shopping is a mile or two away. Major employers, regional parks, culture, and shopping are all located within the 15-minute walking and bicycle sheds. In some cases, you have to cross or travel along automobile-oriented thoroughfares, so we still have work to do. But we are closer to the 15-minute city ideal than many communities.

Communities still need to plan for diversity on the neighborhood scale (5-minute walk). We need small parks, playgrounds, and a variety of housing—including some that is truly affordable—in close proximity. We need diverse people and a mix of uses nearby, including third places like coffee shops or taverns. The neighborhood is still a basic building block of life. But we need to think about how neighborhoods and districts fit together, and how all of our needs can be accommodated in a larger area. We can learn a great deal from traditional neighborhoods. And yet, in the 21st Century, the geography of our lives has gotten bigger.

Proximity and human-scale are vitally important for sustainability and livability. In the latter half of the 20th Century we made a big mistake to gear land-use planning to the automobile and discard the human scale. And yet our needs and desires are no longer contained within a single neighborhood. That is why we need the 15-minute city, with its layered sheds: including the 5-minute walk, the 15-minute walk, and the 15-minute bicycle ride.

We need the 15-minute city as a planning ideal to create truly livable and sustainable communities for coming generations.