What good are planners if zoning disappears?

M. Nolan Gray has good timing with Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix it, one of the top selling urban planning and development books of the year. Zoning is being challenged like never before in the century since it caught fire as a public policy.

Zoning reform is gaining bipartisan political support at the state and national level. The Atlantic recently published an excerpt of Arbitary Lines—a sign that the book’s ideas have intellectual currency. The interest is due to a growing recognition that zoning has been a force for inequity and exclusion, while it suppresses the production of more affordable “missing middle” housing types and necessitates costly automotive travel.

Leaving those arguments aside, Arbitrary Lines is intriguing because it tackles the question—what will planners do without zoning? The administration of zoning laws, and other regulatory tools like minimum parking requirements that are also under intellectual attack, have consumed much of the day-to-day work of public sector planners for generations.

Freed from the constraints of administering voluminous regulations of dubious value, planners could shift their energies to work that makes more important contributions to quality of life, he writes. Some of this work aligns with what new urbanists have been trying to do for decades.

“We must revive planning institutions of yore, with planners thinking through plans for future streets, parks, and public facilities, in advance of growth and in a way that is fiscally and environmentally sustainable,” Gray writes.

“Left without a plan, cities will have streets. But historically, these would typically end up a tangled mess of narrow leftover lanes at the edges of properties.” That’s why planners began laying out street networks, such as the late 1600s plan for Philadelphia by Thomas Holme, or the 1811 plan for Manhattan by John Randel. He explains.

“Beginning around the mid-twentieth century, this type of nuts-and-bolts planning curiously fell out of fashion. As a result, many of the American cities that boomed after World War II are a mess of overbuilt arterials, underbuilt country roads, winding side streets, and dead-end cul-de-sacs, a public realm driven by the uncoordinated plans of developers, lacking any thoughtful planning oversight. The result is an urban form that is outright hostile to pedestrians and bicyclists, and barely functional for drivers. The siting of parks is irregular, if it happens at all, while school construction authorities must negotiate with developers for sites on the periphery as they scramble to accommodate population growth after the fact. It doesn’t have to be this way: with a clearly defined public realm, planners could ensure that new growth is integrated into a broader vision, with new projects paying their way.”

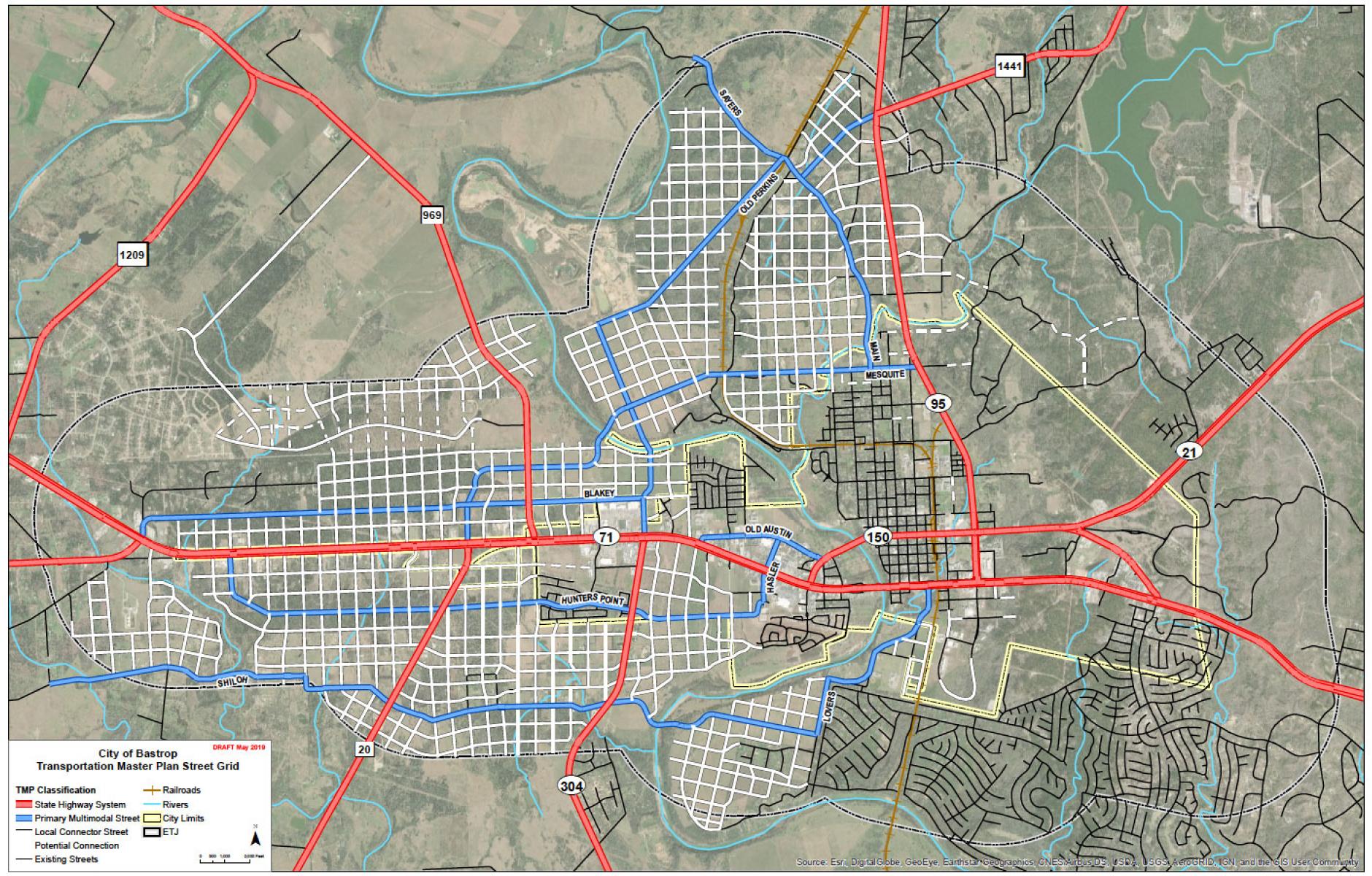

Physical urban planning has lately started to make a comeback, says Gray. Citing a Public Square article, he notes that a few cities have begun to plan for growth on street grids. The most notable example is Bastrop, Texas. The “Bastrop block” addresses concerns about stormwater flooding, and seeks to replicate the most beloved part of town.

There’s also a great deal of work needed to undo the inequities that have been caused by zoning, Gray says.

“The first priority for planning in a post-zoning world should be opening up those affluent neighborhoods and suburbs that have historically used zoning to exclude the less affluent,” he writes. The US remains highly segregated by race and income, he explains, noting that planners can help to accomplish two broad goals.

“In affluent neighborhoods and suburbs, this will mean integrating low- and moderate-income

housing into high-opportunity areas—that is to say, those areas with easy access to good jobs and quality public services. In a gentrifying context, this will mean keeping low-income families in place as neighborhoods gradually desegregate.”

Gray identifies tools to accomplish those goals, including low-income housing tax credits, Section 8 housing, and community land trusts. He is not a fan of “inclusionary zoning” because, he says, it raises housing costs. But there are many creative ideas that planners could try if they were not administering zoning regulations.

Also, planners could do a better job addressing real nuisance issues, such as noise, smells, vibration, trash, light pollution, etcetera. “Where ordinances regulating these baseline quality of life issues already exist, planners should dive into them, developing clear and measurable standards,” he writes. “Perhaps most importantly, cities should work with city code enforcement officials to ensure robust and equitable enforcement. Clear rules tailored around specific nuisances, thoughtfully designed and consistently enforced, will go much further in advancing urban quality of life than zoning ever could.”

Not everything can be solved by regulation, so planners should sharpen their mediation skills. A planner by trade, Gray tells the story of a bar moving to town, “sharing a property line with homes along the back of its lot. The bar was noisy and had lined the building’s parapet with garish neon lights—both understandably offensive to nearby residents.” A planner diffused the situation by talking to the bar owner, getting him to make low-cost changes to avoid a potential lawsuit.

Planners could gather data on trends that really matter in a much more systematic way. “Undertaking this type of active planning means collecting and analyzing data on demographic, economic, and environmental trends on an ongoing basis: Where is new housing construction occurring? What types of people are moving into this housing? Where is new office development occurring? How do these people commute to work? How are temperature and precipitation patterns changing? What areas are newly threatened by extreme climate events?”

All of these are good ideas—some urgent needs that are addressed in a piecemeal and haphazard fashion, others long-term needs that are neglected—that planners could focus on if they weren’t micromanaging uses and parking. Even if, as seems likely, zoning stays with us for a long time, less stringent and more sensible codes could allow planners to move in several more productive directions. Gray is doing a service by initiating that discussion.

CNU will have host Nolan Gray for an On the Park Bench webinar on August 2. Register here.