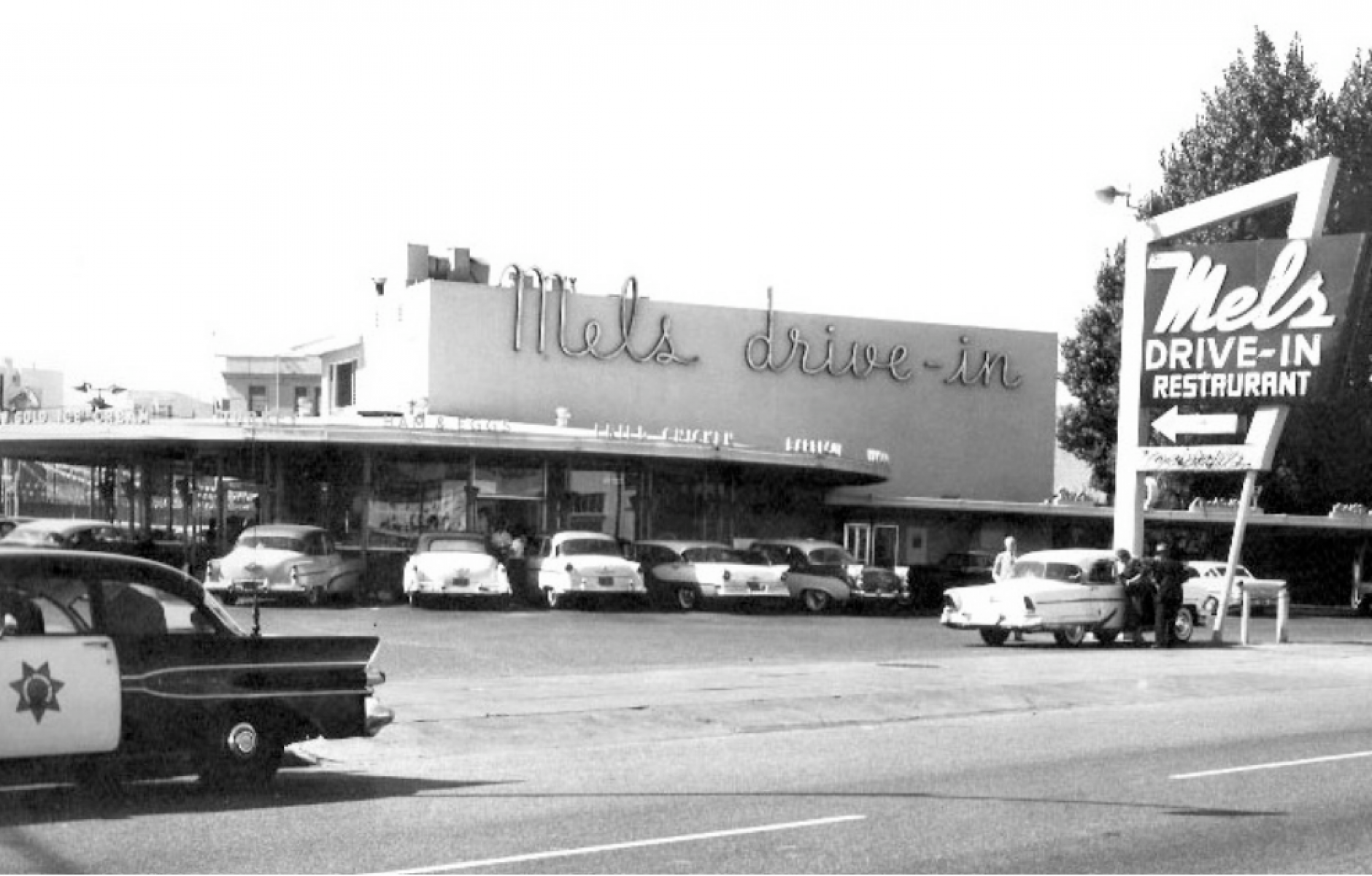

The American strip is a relic

“The Strip” was once the glue holding together the American Dream’s new world of subdivisions, shopping centers, and office parks. It was the place to cruise, a new type of social space, lined with landmarks, trademarks and yes, gathering places. But no more. Today we do our cruising online and much of the brick-and mortar commercial life of the strip is in decay. The strips of commercial arterials hold the potential to be reborn as Grand Boulevards and be the center of an even more vibrant social and community life.

We have overbuilt strip retail throughout our inner suburbs, historic cities, and towns. America has six times more retail per capita as is average in Europe and to make matters worse on-line shopping is accelerating. This is leading to decay and declining strip commercial values and diminishing local taxes. The days of spreading ever outward in suburbs too distant from jobs and too expensive for many struggling working-class households are long over. The only rational direction is inward; infilling, repairing, and enhancing our existing communities – and accelerating the transition from cars to walking, biking and transit. The catalyst may be the soaring demand for new housing.

One of the lessons of the mortgage crisis of 2008 is that American’s need more affordable housing options, especially near existing services, transit and jobs. California’s housing deficit is over 3 million and growing; since 2008 housing production is half of the state’s historic average and restarting single-family subdivisions in more and more remote locations will not solve the problem. The next generation of housing in America should focus on workforce housing – the places and prices that make sense for the struggling working families along with the needs of singles, elderly, and empty nesters. Today only 18% of households are married with kids, and a smaller percent of those can afford the price and the commute of a new Single-Family subdivision.

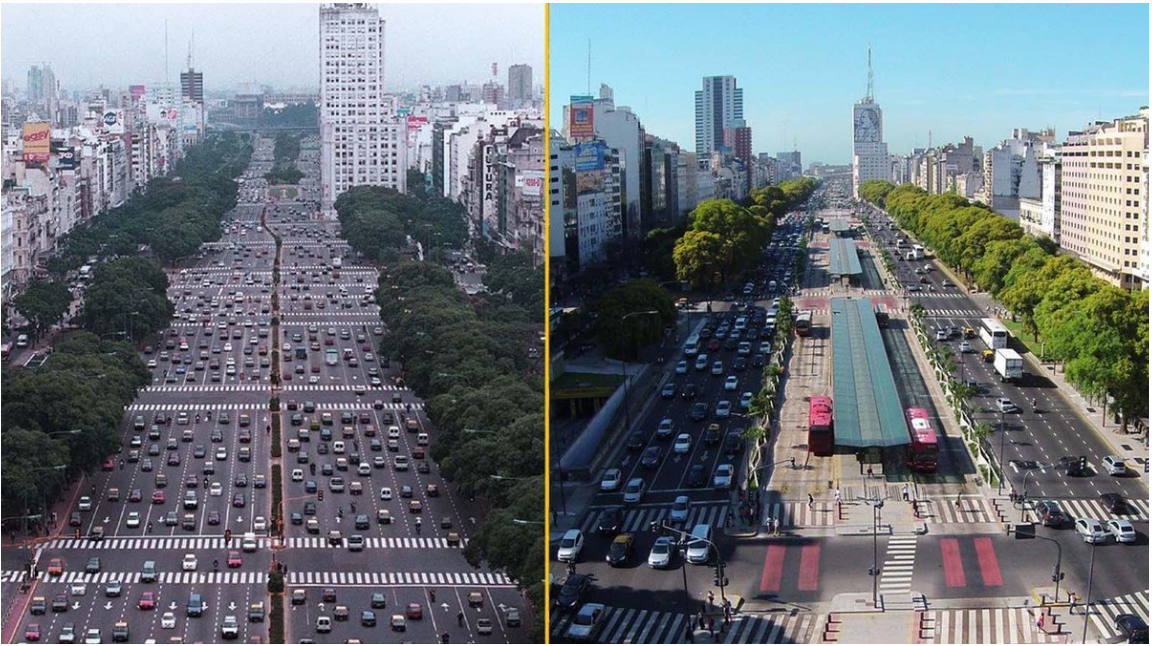

Grand Boulevards combines the need to retrofit strips and provide more housing into a simple comprehensive solution: convert undervalued and underutilized strip commercial to mixed use, mixed income workforce housing. Depending on size of parcel, road size, and proximity to transit, a rich combination of townhomes, live work, missing-middle multiplexes, lofts, condos, and midrise apartments are possible – many with ground floor shops and services. At the same time there is enough road space to convert the auto-only asphalt nightmare into a livable, multi-modal boulevards with new transit, bikeways, trees, and generous sidewalks. Ribbons of compact walkable environments will then reconnect our complex metropolitan regions, weaving between local communities and job centers while providing massive infill housing opportunities.

This infill housing strategy will upgrade the dying strip while distributing infill housing without disrupting stable neighborhoods or displacing existing housing. And as a bonus, the increased property values will provide a tax windfall for state school funding as well as local public investments in transit, parks, affordable housing, and services. While not invading stable residential areas or tearing down older affordable apartment buildings, this strip commercial land will be rebuilt with mixed-use structures, keeping retail businesses on the ground floor while adding condos and apartments above.

For example, the underutilized commercial land lining the Inner Bay Area’s 700 miles of arterials total 15,400 acres. This land could provide up to 1.3 million new houses with 260 thousand affordable units close to jobs and existing services. When compared to the impacts of an average Bay Area house, these Grand Boulevard dwellings would generate 55% fewer auto miles; cost 53% less in utilities and transportation; consume 39% less energy; demand 62% less water and produce 50% less greenhouse gas emissions.

California State Legislation Passes

The ‘Affordable Housing and High Road Jobs Act’ (AB2011) in California is the first major step to implement such a vision. It can be a model for other states struggling with housing deficits, dying commercial strips and the environmental costs of sprawl. This groundbreaking legislation allows ‘as of right’ and streamlined environmental reviews for a variety of mixed income housing on strip commercial land. It requires a range of min densities and max heights, along with market driven parking allocations, fair labor standards, and mixed income construction throughout. And it includes urban design standards that will shape active, safe and livable environments.

Our study with UrbanFootprint finds that a total of over 8 million units could ultimately be constructed statewide on 108,000 qualified acres of strip commercial land, with around 2 million units economically viable in today’s supply-chain stressed economy. As commercial land values continue to decline, and construction costs normalize many more may ultimately be built. If just 10% of these ‘market feasible’ units were produced annually, overall state production would more than double from current levels of 120,000.

In addition, 15-20% of all this new housing is required to be affordable, resulting in up to 400,000 total units for low-income households and potentially increasing annual production from the 2020 level of just under 17,000 to close to 60,000 per year. All this without any direct government investment, allowing the state’s limited housing subsidies to focus on homeless and very low-income needs.

The bill is revolutionary in many ways. It will reduce entitlement costs and support needed density, diversity, and housing opportunity by overcoming local NIMBY opposition to infill housing through delay or exclusionary zoning. The law is the first state level ‘form-based code’ framing a range of height, setback, and active street frontage requirements based on parcel location, size, and proximity to transit. It sets minimum densities from 30 du/ac on small parcels to 80 du/ac near transit to ensure that the ‘place value’ of these sites are fulfilled. It allows the market to determine parking needs, minimizing housing costs in areas where reduced or auto free living is viable. Finally, it supports the needs of construction industry workers by requiring prevailing wage, training, and benefits. And a massive influx of new jobs.

Pushback from local government and NIMBYs was minimal, partly due to the precision of the bill avoiding any residential demolition or redevelopment in stable neighborhoods. The local tax implications of the bill reversed the long-held notion that the cost of supplying services for new housing outweighs property taxes generated. A companion study by EPS points out that property taxes contribute on average 45% general fund revenues to cities, approximately 2.5-times the contribution of sales tax revenues. Their analysis finds that housing enabled by AB 2011 could have assessed values 20 times greater than the existing commercial properties. Moreover, these tax increments can underwrite municipal bonds to pay for even more affordable housing, mobility improvements, expanded parks, and local services. All multiplying the impact of the bill.

Next Generation Transit

Too often rail transit, light or heavy, is too expensive to span the needs of America’s decentralized metropolitan regions. But bus service while needed as a last resort for many, is too slow to be attractive. If regional transit networks are scarce, slow and expensive they have little chance of moving people out of auto trips.

On ‘Grand Boulevards’ the next generation of transit could emerge to complement new density and higher levels of activity. First, creating exclusive transit lanes (BRT) with faster electric buses would create a broader network of transit with more walkable accessibility. Then replacing them with autonomous vans that use smart algorithms to cluster origins and destinations to provide on-call semi-express trips 24/7 would optimize the system. Faster and less expensive to build and operate than any current transit system, this new transit tech is currently being tested in Singapore. Called Autonomous Rapid Transit (ART) Fehr & Peers, a leading transportation firm, estimates the construction cost at just 15% of most light rail systems, with half the operating cost, all while moving passengers 30% faster. Fast, cheap, and ubiquitous may be just the ticket to get people out of their cars – especially if they live on the boulevard.

Grand Boulevards can provide places to live that are more affordable to working households, and cities – and more favorable to the environment. The aging strip across America is underutilized and undervalued – an opportunity to solve our most critical housing and transportation crisis – it is a chance to transform the least loved part of our communities into thriving, living assets. All we need is the political will and vision to support this transformation.