Great idea: Shock and awe for cities and towns

In celebration of the upcoming CNU 25.Seattle, Public Square is running the series 25 Great Ideas of the New Urbanism. These ideas have been shaped by new urbanists and continue to influence cities, towns, and suburbs. The series is meant to inspire and challenge those working toward complete communities in the next quarter century.

Civil engineer and planner Charles Marohn and architect and real estate analyst Joe Minicozzi took part in a panel discussion in 2011 at CNU 19 in Madison, Wisconsin, and they both describe it as "chocolate and peanut butter meeting for the first time." Marohn helps government officials and citizens understand the infrastructure efficiencies of traditional towns and neighborhoods; Minicozzi analyzes land-value economics and promotes development patterns that secure a community's fiscal sustainability. They have opened the eyes of America to what Marohn calls the "Ponzi scheme" of 20th Century development patterns and the relative value of mixed-use urban places.

Public Square editor Robert Steuteville interviewed Marohn, founder of Strong Towns and Minicozzi, principal of Urban3, on the economics of development and infrastructure, and value and efficiency in land use.

I wasn't even sure quite what to call this, but I'm thinking of "Development and Infrastructure Value and Efficiency." There may be a snappier title for what you guys do—any ideas?

Marohn: "Shock and awe" is what we call it.

Minicozzi: Yeah, "shock and awe" works.

So which one is shock and which one is awe?

Marohn: I'm definitely shock. Chuck is shock and Joe is awe.

Minicozzi: We all know that sprawl costs money, but no one's explained at that detail about the cost of sprawl the way that Chuck explains it. When Chuck and I do presentations together, we get to see the audience. We can see their reaction, and there's a palpable sense of shock when Chuck starts walking through the cycle of suburban infrastructure. It's very obvious that everybody realizes that you can't build your way out of it. It just doesn't work financially. The audiences have to wrestle with that. But I'm sure Chuck can tell you many stories about it.

Marohn: You watch people struggle because part of the cognitive dissonance of Americans is that we know what we're doing doesn't make sense. But, we really don't have a formulated alternative to wrestle with and ponder. So it's easy for us to just go about our days and not think about it much. When we put it in front of people and we walk them through, it’s like, "You actually know this. You know why this doesn't work. Here it is." It is one of those pulling back the curtain kind of moments. You know what's on the other side, but now you're seeing it in such high fidelity, such great contrast, that you can't ignore it. And you can't unsee it. You have this new world open. The reassuring thing then is to have Joe step up and say, "Look. We actually know how to do this. I mean, we've been building great cities for thousands of years. Here's how to actually deal with these problems that Chuck has shocked you with. We actually are good at this. And the math starts to work out and make sense, but you've got to measure things differently. You've got to look at it in a different way."

So once you can hit them with the shock and awe, what is the next step? Where do they go from there? Can you give me an example of a place or a community that came to this realization that this was economically unsustainable and actually did some meaningful things about it?

Minicozzi: Lafayette, Louisiana is wrestling with this right now. We programmed the roads and pipes and the sewer system, all that stuff—the same way that Chuck runs it as a subdivision in his presentation, we did that citywide and showed people the economic state of the city.

And what have they done?

Marohn: You look at a place like Lafayette and you realize that there's no solution in the sense that we can fix everybody's problems. What Lafayette has done is really lead the country in asking a harder set of questions. And in Lafayette they have now realized that they can't just accelerate their way out of this problem. They actually have to start thinking differently about things. And this is a long process. They haven’t come up with a plan to attack this. But they're no longer ignoring the problem like most other cities are.

Minicozzi: And I think what ties this all back to New Urbanism is there are so many things that go into it. A lot of our peer groups and organizations that try to gravitate towards the simple solution, the magic bullet, all of those things. We know that that won't work. Lafayette's situation is a 40-year problem. So it's going to take a while to unpack that and undo some of the damage that they've done. And our recommendations weren’t just one thing. They were: Start reinforcing your downtown; Change the way you do your budget process. That's totally unsexy. In this process, something as unsexy as that is actually going to have a big effect when they start doing true accounting for their infrastructure.

Marohn: I think the really important thing about the whole shock and awe approach and the work that we're doing with Strong Towns is that, it really has no kind of partisan bite to it. We don't start with a point of view on the political spectrum or a sense of here's what is morally right and wrong and then try to find data to justify that. We lay out data and let people put it in their own paradigm. And I think that has made it, not only more powerful, but more relevant for America today. We've been invited many times to go speak in really, deeply conservative red places. And we've been also asked to go speak in very liberal, political blue places and our message is equally received in both. And it's because the dollars and cents really get beyond the partisan divides and deal with where cities are struggling.

Minicozzi: It's just being agnostic about the data. The data is telling you exactly what's going on, just use it.

And you folks seem to work a lot in towns and sprawling metros. It reminds me a little bit about of the story of Andres Duany tells of when two successive nights where he worked in Boston and then in some rural area in California. And it was a completely different audience and they both got it.

Minicozzi: What the audience starts to dial into is, why do we not use this collective knowledge? They start to understand that urbanism is not a bad word. I just did a presentation in Johns Creek, Georgia, which is a suburb of Atlanta, 30 miles outside of downtown. It's 82,000 people, and they don't understand why they don't have a downtown. They're 20,000 people larger than the population of Greenville, South Carolina. They're gradually waking up to the idea that this is foreign to the concept of human habitation. We've got 10,000 years of city-building experience that we've neglected in the last 40 years.

Marohn: Joe and I, once, were in Greensboro and to hear Joe talk not only about the finances, but then talk about the way people were building things years ago and why it was set up into these core neighborhoods, you got a real sense that people were really smart, not necessarily IQ smart, but they were trial and error smart. They had figured out what worked. These traditional development patterns, by trial and error, figured out how to build places that not only worked for people but also were financially strong and resilient. And to me, when I look at the graphics Joe puts together, the analysis of say Buffalo, New York—and you think of it as being a place that was hollowed out after World War II and just in a state of perpetual decline. And then you look and you say, "Oh, my gosh." Even with all the decline, these old traditional neighborhoods are still enormous assets that really dwarf everything else. And it just makes you realize how powerful this way of building was and how tragic it was that we just walked away from it. But then also how easy it would be to recapture those principles and put them back into play in our cities.

How do you get people excited to recapture those principles?

Marohn: At Strong Towns, we're really good at helping people ask a different set of questions, and see things differently, and start to visualize the world they live in, and the world they could live in, differently. I feel like we're paving the way for a broader acceptance of new urbanist practices.

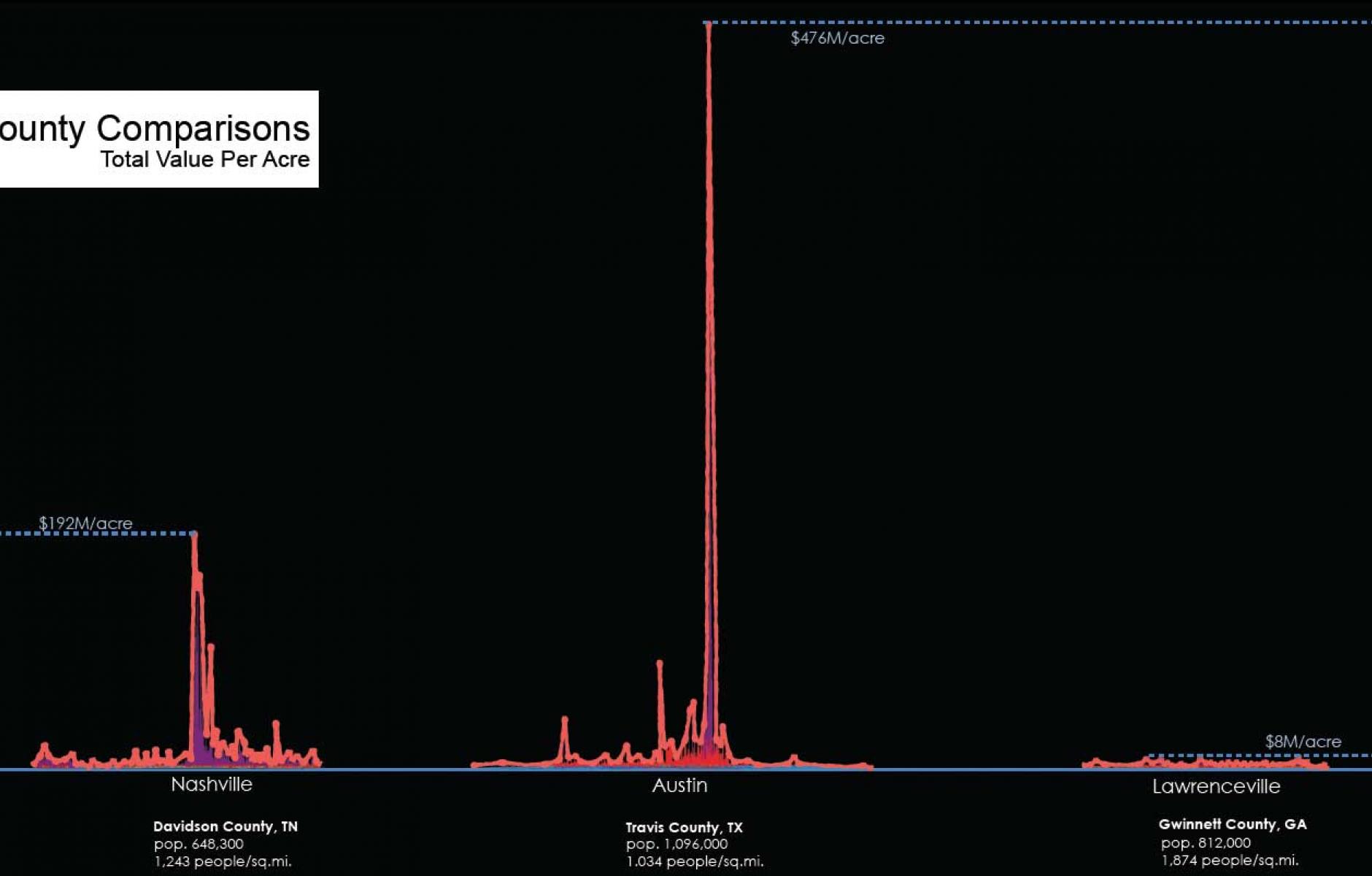

Joe, you've gone around scores, maybe hundreds of municipalities, and you've done plans that show the value. They show the peaks of value of the downtown, and they dramatically bring home that point of where the tax revenues are coming from. Do you ever get frustrated that after 100 or 200 of these maps that you still have to do another one for each new community you go into?

Minicozzi: Not really. It's a complex thing to answer. You're dealing with political leaders that want to do the right thing, but they don't have a full understanding of how municipal finance works. Both Chuck and I have worked in and around government and dealt with those processes, and the process tends to drive everything. And so they don't get a chance to sit around and think about this stuff. So it's not an easy thing to unpack. I don't get frustrated with my clients. I appreciate the fact that they're asking deeper questions. Like in the case of Lafayette, kudos to them for wanting to really get into their books and see how messed up they are. A lot of cities will just keep on going down the road.

Chuck, you've been writing in particular about how important infrastructure is right now, as the Trump administration gets underway. Could you give me your thoughts on infrastructure as a national issue?

Marohn: What we’ve seen over the last 60 years is that there are really horrific things that have happened in our communities, as a result of these centralized objectives, and then cities have to deal with the consequences. And what we would really like to see is an agenda that focused on cities first and their needs, and then worked itself up from there. And the urgent needs that we have in our cities today are really of the fine-grain variety. If we spent our money working on crosswalks, and planting trees, and converting single family homes in struggling neighborhoods into duplexes and triplexes, and getting more wealth off of the sidelines in our communities and back onto the blocks, we’d transform this country. Instead, we’re going to talk about big interchanges and bridges and highway expansions, as if we’re not already drowning in liabilities that we can’t maintain.

So is there any way that you see that all this proposed spending is going to be able to be put to more productive use through the federal government, then through the states, and then through the local municipalities?

Minicozzi: No, but, we've said sometimes, "How can we do this in a way that does the least amount of damage and has the highest potential for ultimate ultimately doing good?” And we've come to the conclusion that if we spent the money underground in old neighborhoods, essentially water and sewer systems, that would actually give us options down the road, instead of a whole bunch of liabilities. We can go back to Lafayette, Louisiana, and we can see that in their core downtown, where they actually have the most financially productive neighborhoods, neighborhoods that are very poor yet pay more in taxes than they require in services, one of the biggest threats to those neighborhoods is the fact that a lot of the pipe there is old, clay pipe. It's stuff that's cracked and settled and needs to be replaced. You go to the edge of town, where they're building stuff brand new, and they've got brand new PVC pipe that will be in the ground for a couple generations without needing a whole lot of work in maintenance. But these places are deeply in the red. They require a lot of ongoing cost and maintenance expense, and they don't pay on a per foot basis very much in taxes.

One thing I'm struck by looking at some of Joe’s maps is that these new urban projects actually show up in your images. If there's a new urban project, all of a sudden there's a peak which shows the tremendous value that's created in a smaller area.

Minicozzi: It's unbelievably simple math—new urbanism is essentially mimicking old urbanism. The old urbanism is potent because it's dense and it's multiple stories. When you stack one story on another, you're essentially stacking your dollar bills for your taxes.

Is this an affirmation of the concepts of New Urbanism?

Minicozzi: Yes. Here we are, we've become the wealthiest nation on the planet, and we just get silly with our money and don't think about how to get it back. And so there is a pattern that we can learn from older civilizations. The original people of Lafayette, they didn't build in the swamp because they were broke. And so the biggest problem, the reason why, when you look at that model of the upside down infrastructure, the biggest thing dragging it all down is all the storm water systems that are out in the swamps. Well, that's a no-brainer, like why would you build in the swamp? You can't fight Mother Nature—it's expensive. And that's the simple math of that model, of course, they're going to be upside down financially.

Marohn: I think too, you know, to me the best of New Urbanism is when we start with humility and work at a really small scale with an incremental intent. The thing about New Urbanism that works best is when people just roll up their sleeves and look at a routine problem and say, "Look. We can fix that, and we can fix it without needing some huge historic intervention and without some big, top-down kind of process. We can just make some little things here, and if we follow some principles, we can actually come up some with something that's a lot better."

Do you see cities and towns moving towards that understanding and realization? Or is it just pushing the boulder uphill once again?

Marohn: No, I think that the biggest challenge we face at city-level is that cities have bureaucracies and processes that are very post-World War II. They're very suburban-oriented. Until our governments are able to restructure themselves, we're going to struggle to get things off the ground. You can go to a place like Detroit and see where humility has been imposed on them. Some of the best things in this country right now are happening there, where they've had to roll up their sleeves and say, "Let's rethink this."

By the same token, it seems to me you've got two things going on. You have these sets of top down practices and regulations, which have created a certain built environment. But at the same time, you've lost the cultural memory of how to do it in a bottom-up way, efficiently. Seventy-five years ago, if you asked people to simply create a main street, they would have done it a certain way almost without thinking, because there was a cultural memory. So how do you get that back?

Marohn: I think there's knowledge that certainly has been lost and can be regained, but there's also the realization that we're very different today. And we're going to have to use those techniques to figure this out as we go ahead. We can learn from the way that they approach problems and the way that they did things, and use that as a starting point to say, "How do we hack and retrofit what we have today to actually make it work and make sense?"

Speaking to an audience of urbanists or planners or public officials, are there any final thoughts on things they need to know that are really critical?

Minicozzi: You can throw a tremendous amount of money at a project and make it look really nice from a design standpoint, but it may not function financially in the long haul. So having the municipal finance conversation is really key.

Marohn: I would say that you have to do the math. We can build places that are beautiful and walkable and well-connected and meet all the other metrics, but if they're not financially solvent, it's going to be for naught. And so unless we take care of the money, it's not going to work. We can build places that are fantastic, that are also financially solvent. And I think when we use that discipline, what we find is that New Urbanism comes out ahead of every other approach that's out there.