Great idea: The public realm

In celebration of the 25th Congress for the New Urbanism, Public Square is running the series 25 Great Ideas of the New Urbanism. These ideas have been shaped by new urbanists and continue to influence cities, towns, and suburbs. The series is meant to inspire and challenge those working toward complete communities in the next quarter century.

Complete streets are more than bike lanes, crosswalks, sidewalks, and vehicle lanes; they are buildings that engage the people in the right of way. Well-designed plazas, squares, and greens are framed by landscape design and architecture that relates to local culture, history, and climate. New urbanists have long advanced the idea that the public realm ties cities together and is a potential source of joy and inspiration to all citizens. Former Bogota mayor Enrique Peñalosa may have said it best: “Great public space is a kind of magical good. It never ceases to yield happiness. It is almost happiness itself.”

Public Square editor Robert Steuteville interviewed architect, urbanist, and author Dhiru Thadani, based in Washington, DC, and urban designer Howard Blackson, based in San Diego, California, to discuss the public realm, cities, towns, and civilization.

What is the public realm, and why is it so important to the New Urbanism?

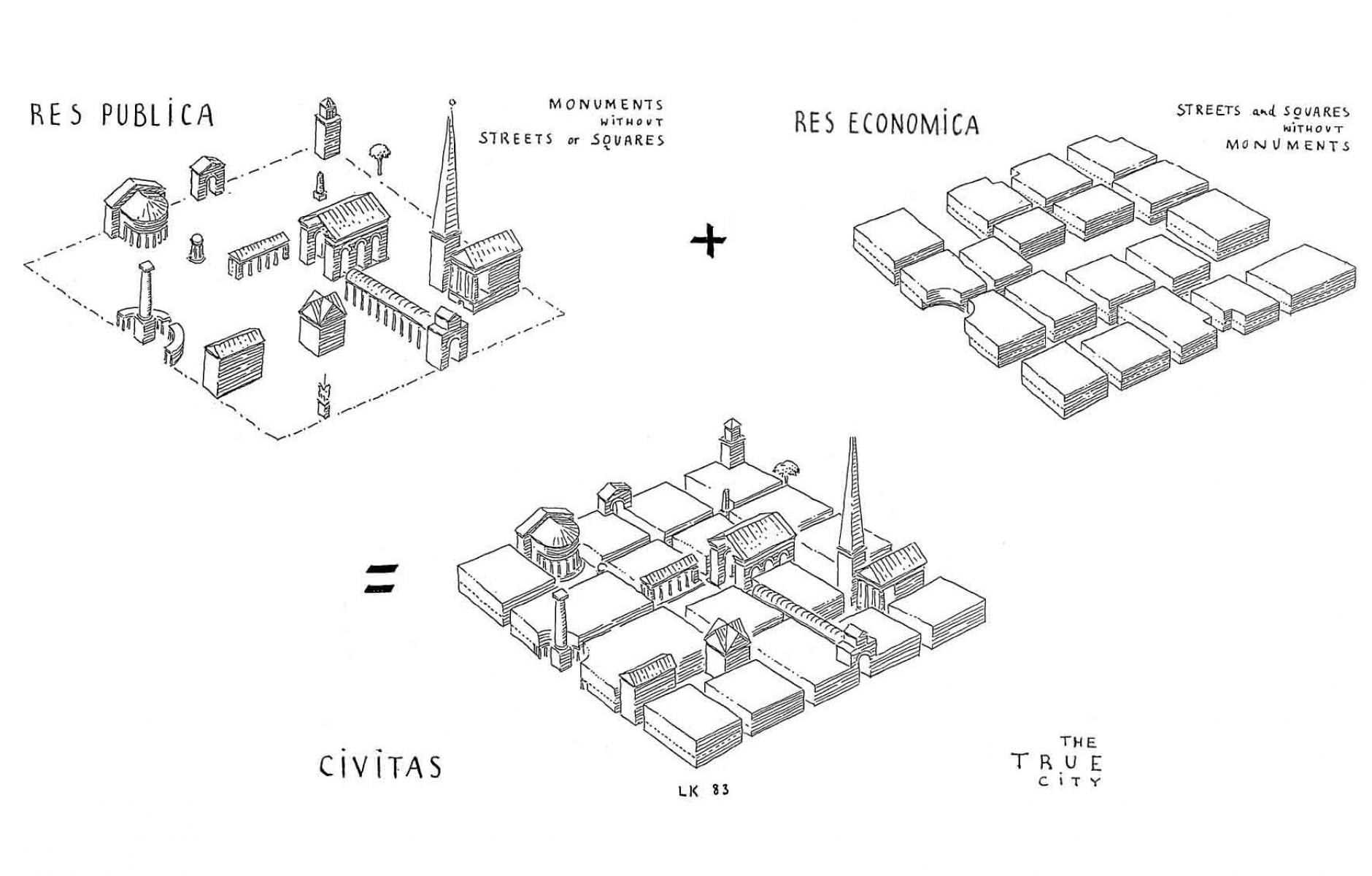

Thadani: Any conversation about the public realm has to go back to Léon Krier's diagram from the 1980s. It’s a really good starting point for an appreciation of the public realm. Léon made that drawing in '83, when he received the plans for Seaside from Andres Duany and Robert Davis as a way to explain the two realms of what makes a true city. For a lot of folks, this was the aha moment—we saw that diagram and started to understand what was wrong with non-urban areas—sprawl, suburbs, whatever. It clarified that the public realm and the civic buildings were an important part of a true city. And the street was an important part of the public realm—it was the connector between public spaces.

Blackson: It was a return to the patterns of a public realm being streets and parks—and forming blocks and buildings. Whereas, the modern idea from the '30s to the '70s, that had all been obliterated. The only reference I had to traditional streets, plazas, blocks and buildings were in burned-out downtowns, or Disneyland. It was a New Urbanism and Léon Krier's diagram that shifted the conversation back from placeless buildings to streets and blocks, to creating places. I think a great Krier quote is, "The architecture of the city and public space is a matter of common concern to the same degree as laws and language. They are the foundation of civility and civilization." Public space and how we interface socially is our civilizing element. And that's of greatest importance in today's politically, socially, environmentally toxic world.

Has this idea been widely recognized? It seems to me that a lot of people just take the built environment for granted, and they don't recognize its importance on the same level as say, laws.

Blackson: I think we do understand it. Pretty much every person, as long as they know “mixed-use walkable urbanism,” talks about getting the ground floor right and everything else will be great. And learning about the importance of the ground floor is the first baby step towards urbanism, away from the modernist experiment on cities. Getting the ground floor right is the civilizing component, but it's just the first step.

Thadani. I think that that recognition has become widespread.

Blackson: We understand traditional urban patterns as streets and squares forming blocks and buildings, and expanding traditional urbanism into architecture. We've marginalized that modernist architecture—modernism is only allowed to live between floors 2 and 26. And now, urbanist architecture is slowly moving up the buildings, so it's getting fun.

For the non-architects, non-urban designers out there, what is it about the pattern of blocks, streets, and buildings, and getting the first floor right that's so important to cities and towns?

Thadani: Let’s talk about walkability. It's interesting to walk by storefronts, to people-watch at cafes. That ground-floor life is what animates the cities. When Howard talks about getting it right, it's really about animating the urbanism and making it interesting. It's much easier to walk in a place with an active building face than it is to walk past parking lots, parking garages, or blank walls. The two are related, the public realm and walkability—the quality of the walkable experience is dependent on street frontage. One mistake is measuring walkability by a metric of the quarter-mile. We don't spend enough time talking about the quality of the experience of the walk. When the public realm has been done well, you can walk endlessly, that’s the beauty.

Blackson: And, now we understand that complete streets are a city's greatest social justice tool. Because they provide the most number of citizens access to commerce, society, and culture. The complete streets and complexity of streets are becoming that next step of public realm design. So, we're seeing this shift from focus on automobiles only to all types of travel modes.

The Charter of the New Urbanism states that "Urban places should be framed by architecture and landscape design." That's a meaningful phrase for me. How does that relate to the public realm?

Thadani: The architecture has to be of its place. It has to respond to the climate, the ecology, and building practice. What we've been doing for the last 50, 60 years, is dropping International Style buildings all over the world. Even if they line up with the street wall and frame the space, they really don’t tell you anything about the culture of the place.

But it’s also the idea that a building has a job to do in terms of creating an outdoor room or a public space that's enclosed as opposed to just a building that's housing a particular use.

Thadani: Buildings and landscape design have an obligation to place, to contribute to the public realm. It's designing a building with reference, both to the physical and the cultural aspects of a place. The word contextualism, which was framed in the ‘70s, had to with both the physical and the cultural context.

Blackson: I was fortunate to witness Leon Krier come up with the idea of tuning the architecture and urbanism to a place in Chico, California. Since then, we’ve expanded on the patterns of the public and private realm in relationship to buildings and spaces. The landscape around the civic building could be tuned differently than the landscape of the private sector. The private buildings could be tuned differently than the public building, and that tuning gives you character, the value and memories of the people living there. This is the next step of architecture and urban design. You can find your missing middle building types and tune them properly according to that relationship between space and place.

Thadani: The key realization after 25 years of New Urbanism is that public space is the umbrella for placemaking. And a lot of planners understand that word placemaking. Urban design done well creates value, because it makes a place that the general public can use as a reference. Two blocks from Rockefeller Center or five blocks east of Dupont Circle—that has a value.

A lot of developers came to realize in the early years of New Urbanism that if they wanted a project to get higher returns, placemaking created value. So building a park or a public space that is recognizable creates a moment within the city. A street is a linear corridor, but once you add the cross street to it, you've made a place. Otherwise you're driving down this endless street, going down for miles and miles, and it's undifferentiated. Now, you expand that cross street, you blow out one corner, and you've created a plaza. You incrementally add to the spatial quality. And that's where the real value is.

Blackson: Now that we've come out of the crash, we've got housing crises, we've got this urban-rural split, and we're concerned with social justice. As I said earlier, the way we inhabit and connect with our streets and our streetscape is the biggest social justice issue happening in cities today. The point of rethinking the street today is to consider the social justice perspective.

So why is it so important that the public realm be walkable and human scale for social justice reasons?

Thadani: It equalizes the condition for everyone. A street right-of-way controls what's privatized and what's not. And that might be frightening to some people because everyone has access—But cities are about access for everyone.

Blackson: And if that access is by car, then you start to suburbanize and you destroy your inner city. If it's by foot, then you can urbanize and create housing opportunities that have been lost to a car-oriented culture.

In 90 percent of our metro areas, we’ve got the opposite of three-dimensional urbanism. The public realm is constantly bordered by parking. It's either parking lots or garages. First, what's wrong with that? Second, do we need that to a certain degree? And how do you incorporate that into an idea of a public realm that's framed by architecture? How do you incorporate some of those uses like the Jiffy Lube or the big box store?

Thadani: It's not possible to have every street an A street, or a complete street. So you relegate some of those auto-oriented activities to a B street, given the present condition. The balance between A and B streets might change over time, but most cities can't afford to change every street into a complete street. Nor should they attempt to do so because we still have cars, and there are auto-reliant uses and services that need to be on those B streets.

Is there a way to make B streets better than they currently are? Does it have to be completely one or the other?

Thadani: B streets absolutely could and should be better. There’s no reason why buildings can’t front a B street. There's no reason why the Jiffy Lube has to be set back 100 feet from the street. Cars could access the building from the back.

Blackson: And a way to make B streets better is to understand that there's C streets and D streets as well. Goeff Dyer and Nathan Norris did a really good job of thinking that through the downtown Lafayette, Louisiana. We need to understand the complexity of street types, just like we understand the complexity of place and building types.

So can we talk about the implications for coding and street design in a human-scale public realm?

Thadani: The fundamental goal of early form-codes was to get the street right. It stems from the zoning codes, which usually changed uses in the middle of the street. The street became a dividing line that separated one classification from another classification. And so the idea of changing uses at mid-block is a tremendous contribution. Nowadays there is more sophistication. Buildings can be the same type, but it's not always the same lot size so that the houses can have some variety on either side of the street.

You've mentioned something that's important. You said that the street became something that separates. And new urbanists, and the idea of the public realm, focuses on making the street becoming something that unites people.

Thadani: That's the essence of the public realm; that it is a place and not a divider. And because in some streets you have high-speed automobiles going through, the cars contribute to that division because people don't want to cross that street.

You don't even want to be there let alone cross the street if the cars are going fast.

Blackson: And the reason that this still happens despite the new urbanist idea of place-based, context-sensitive, form-based coding is that traffic engineers are in charge of the public works street division. Parks and recreational departments are in charge of the parks. And then the planning department will think about how to shuffle the private buildings around. General services will take care of the public buildings and the libraries, and the city halls. And all of these are coordinated by a city manager or a mayor who's a short-term politician.

In the age of privatization, we are losing the public realm. If you and I want to protest, the best place to go is a freeway overpass with our signs because that's where the majority of the citizens are sitting at eight miles an hour or less is in the freeway at 5 o'clock. Instead of the freeway overpasses, it should be in the plazas and the squares in the cities and the towns where we can sit and talk to each other and work things out.

You talk about the transportation engineers. They do have a tremendous impact on the public realm. From the state DOTs to the city engineers and the big engineering firms. How do we get them to think more about the public realm and recognize the many functions of the street?

Blackson: We vote for transportation and transit, and bicycle facilities. And the citizens have voted for them. It's a matter of continuing to put the pressure on. That stuff is working, and it shows economic returns, but it takes public investment. It's not subsidizing, it's investing.

Thadani: There's so many people involved in this. It just takes education. What I've learned after years of practice as a planner is that you have to be an educator. I think it’s our key role as new urbanists: to educate folks to understand these concepts.

Blackson: And show them how it's done. Because we've been doing it for 20 plus years, and we're the group that can claim that.

Thadani: I just have one other thing I wanted to add about the public realm. When cities were formed they were about commerce, exchange of goods, and transportation nodes. The exchange of commerce, ideas, activities, politics, the marketplace—all that happened in the public realm, and that's how civilization prospered. In the American context, we think of the public realm now mostly as shopping. But that's taken a downturn, so we can't really activate the public realm anymore relying just on shopping. We have to make civic life the impetus. Every city should activate their public realm, if it's a gallery walk on Thursday night, or a concert in the park or something—that has to be programmed to reintroduce and bring people out again for them to say, "Hey, this is really great. We're out in the public park with other people of different economic means or social classes, etcetera. And we're having a good time enjoying this activity."

Can you talk about some cool projects that you have seen of been involved in lately that introduce some interesting or innovative ideas on shaping the public realm?

Blackson: Geoff Dyer and I had the opportunity to use Léon Krier's "Old Four Corners" 'wiggle' to create a "New Urban Plaza" in the heart of downtown Chula Vista, California. The plaza was created by a slight diversion, or wiggle, of the roadway within the right-of-way, to offset the monotonous grid and create a visual and physical center. The traffic is first calmed with an overhead ceremonial gateway sign, brick surface material and a change in street pattern, seating areas, bulb-outs, and bollards to calm the traffic, the 'plaza' is pedestrian oriented, maintains traffic flow while hosting weekly farmers markets. The plaza is planned to be fronted onto by a new Veteran's Memorial Museum as well and is considered a great success.

Thadani: Since I just received my copy of Val D’Europe: A City Vision, there are several beautiful urban spaces in this new city project near Paris, France.