The urban dimensions of climate change: Lessons for a New Urbanism

There is an intriguing paradox within the inventories of greenhouse gas emissions per capita—the emissions that each of us generates through our daily activities of moving, interacting, and consuming resources. Those who live in an average settlement in the United States consume and emit on average about twice as much as those who live in an average European settlement. A comparison of the same US population to, say, the city of Stockholm, produces an eye-popping result: Stockholm residents emit one-sixth as much on average as US residents.

This is a paradox, because Stockholm residents are clearly not one-sixth as wealthy (on average they are wealthier) or one-sixth as happy (in many surveys they are happier) or lower-scoring on other metrics of health and well-being. It seems they are merely one-sixth as wasteful of resources, for a roughly equal (or higher) level of prosperity, happiness and well-being. What lessons can we learn from this disparity as urban practitioners? Quite a few, I think—and they go well beyond the specific issue of climate change.

Of course, one can attribute some of the difference to factors like variations in government policies, energy sources, climate, culture, and so on—but none of these can come close to explaining a magnitude as large as six-fold in emissions. The one variable that is most explanatory, as my own research has concluded, is the dramatic variation in urban form. In Stockholm, the settlement form is walkable, mixed use, compact, well-served by transit—all the characteristics that are celebrated in The Charter of the New Urbanism. In American settlements, the overwhelming majority is still “conventional suburban development”—sprawl by any other name.

As New Urbanists have long pointed out, this form of settlement has several distinctive characteristics that are unique in human history. First, of course, it is built largely around the automobile, on which most residents are dependent for even the most routine short trips (penalizing the elderly, the young, the infirm, and the poor). Second, its uses are functionally segregated—homes, workplaces, commerce, institutions—producing more and longer trips on average, and lower levels of interaction and synergy between uses. Third, its urban form is low-density and spread out, causing even longer trips by car, as well as more extensive infrastructure and characteristically more energy-intensive building forms. And fourth, it has a markedly different structure of public spaces, to the extent that these exist at all. No longer is the city a framework of public spaces made up of streets, squares and parks, defined by supportive private edges and forming a continuous urban fabric through which people freely move and interact. Instead the city becomes in effect a collection of capsules: the capsule of home, connected by the capsule of the car, to the capsules of work and commerce and so on.

The design of these capsules changes too: no longer is the attention on how they form larger wholes, but instead the focus is on how they look and act in isolation.

The consequences of this urban form for greenhouse gas emissions—and for other aspects of resource use, depletion, pollution, and long-term human well-being—are profound, as my own research has documented. The consequences are more subtle, but no less important, for social and economic interaction, for quality of life, and for the ultimate vitality and success of human settlements.

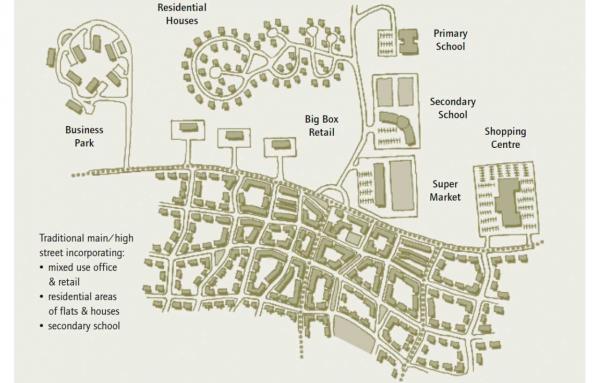

Let us start by looking at greenhouse gas emissions. (But as I will explain later, we will not end there.) The first and most obvious consequence is from the significantly lower density of sprawl. It is intuitively obvious that lower density results in higher distances to travel, and longer runs of infrastructure (see illustration below left). Indeed, research shows that the lower density of a sprawling neighborhood in San Francisco's East Bay does indeed produce a remarkably high profile of emissions, in comparison to the much lower emissions of the higher-density neighborhood of Russian Hill (where I once lived). Indeed, there is a striking inverse relationship between density and emissions, as can be seen on the map below:

This is an interesting finding in particular, because the two places shown here offer us a revealing “apples to apples” comparison. The governmental and legal systems are almost identical, as are the national and even local cultural norms. So too are the energy sources and available technologies. The climates of the two places are also almost the same (the East Bay gets a bit more sun and is slightly warmer, but they are otherwise very similar) as are household incomes. The one factor that is most clearly different is urban form, and of that, perhaps the most evident variable is urban density.

But density is only the beginning of the story. If we compare the morphologies of the two places, we see that the East Bay is similar to other “conventional suburban developments” around the country: largely car-dependent, characterized by segregated use, not walkable, poorly served by transit, and characterized by monocultures of detached single-family houses filled with consumer goods. By comparison, the Russian Hill area is mixed use, highly walkable, compact, well-served by transit, and characterized by many attached and multi-family dwellings (as well as some single-family). These homes tend to be smaller, and the lifestyles of their occupants tend to be less focused on domestic consumption than on exterior urban amenities.

All of these factors add up to a dramatic impact on resource consumption and emissions. Not only does the higher density of Russian Hill contribute to lower per-capita energy and emissions from transportation, but the walkable, mixed urban form also means lower embodied energy and materials in infrastructure, lower transmission losses, lower impact on ecosystems and their services, and the inherent efficiency of attached building forms. In more compact settlements there are also opportunities for district energy, waste, and other more efficient urban systems.

There is also the elusive but increasingly important factor of lifestyle and consumption patterns. In a car-dependent neighborhood, it seems clear there are multiplying impacts from a “drive-through lifestyle” that go beyond the actual vehicle-related emissions, and affect many other aspects of consumption and emissions. The drive-through fast-food restaurant is perhaps emblematic: facilitating impulse purchases of high-calorie meals, containing meat products, generating high waste from packaging, and so on. This behavior is not really the result of rationally examined choice or personal ethics: as recent research into behavioral economics and “choice architecture” show, people often behave in routine ways based upon the choices that are “architected” for them by others within their environments, including their neighborhoods.

So why aren't more people focused on reforming our continuing patterns of sprawl?

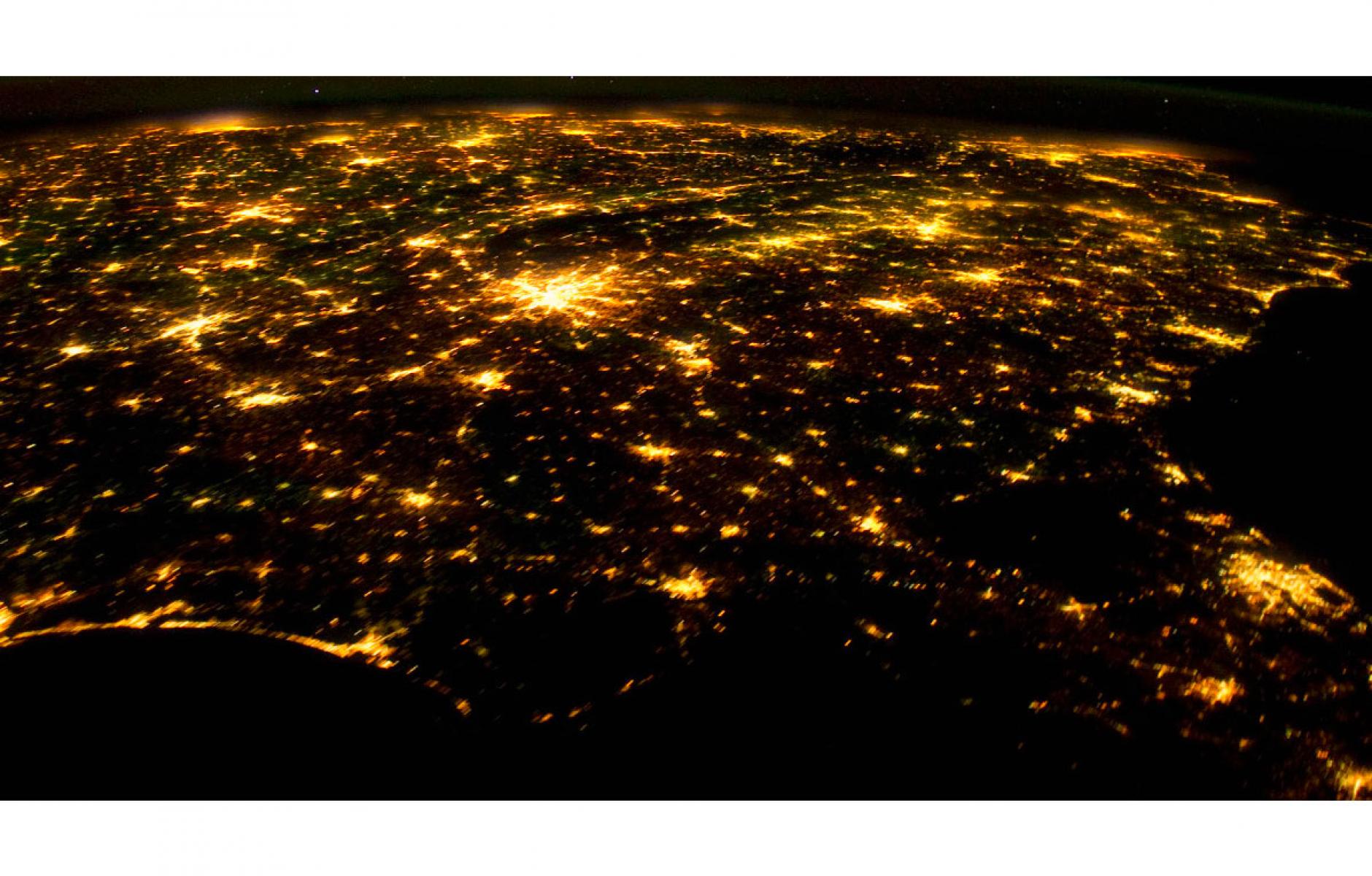

For one thing, the form of cities changes slowly. Designers and policy makers, tempted to look for "quick wins," often turn to technological solutions—but those, as history shows, often don't pan out. In fact, precisely because urban form changes slowly, its effects accumulate over time in a powerful way. The urban infrastructure being built today will be in place, and will continue to shape resource consumption and emissions, for decades to come. It is particularly alarming that China, India, Brazil and other rapidly growing countries are continuing to import a US-style, car-dominated model of growth: that fact alone could easily overwhelm all other efforts at reduction of emissions.

I recently performed a little experiment. I went on a popular image-sharing site, and looked for recently built drive-through McDonalds restaurants in India, China, Brazil and Eastern Europe. My purpose was not to pick on McDonalds restaurants, but to use them as an “indicator species” for the new sprawling, car-dependent urbanism built around them. Indeed it was only too easy to find representative images (below). Again, these are new suburban areas, built within the last decade, with more of this high-consumption sprawl being built every day.

Another reason for the scant attention to sprawl is that it's difficult to grasp all the disparate elements of urban morphology, and how they work in a system to magnify impacts on consumption, emissions and well-being. Small factors together can create a much bigger effect than they may seem to have in isolation. By contrast, it's more tempting to look for discrete “silver bullet” elements to be improved, often with new efficiencies in technology, which are more easily understood. But as noted, sometimes these don't pan out. Perhaps even more importantly, improvements in efficiency can be quickly erased by increases in demand.

A third factor is the idea that consumers prefer low-density suburban patterns, and indeed, families with children often find it a practical necessity. That is often true—but only within the “choice architecture” of the modern built environment. As New Urbanists have long argued, sprawl is not a consumer choice in a vacuum, but a highly engineered scheme that arose from the models of government and corporate planners. Anyone who understands urban morphology knows very well that it is possible to live a very practical and pleasing modern lifestyle in a walkable, compact, mixed urban environment. It is simply rare to have that choice—so we must make it less rare, with new and appealing choice architectures.

Another major problem, growing out of the previous one, is the fact that our global economy is now addicted to sprawl—much as we are addicted to fossil fuels, as George W. Bush famously noted. Sprawl is a major engine of economic growth in many cities, even if it's a toxic and ultimately unsustainable one. Many people can't imagine that it's possible to change this model—even though professionals and policymakers did change the model drastically in the 20thCentury, and structurally speaking, they could change it again. (That's not to suggest this would be easy, as most of us well recognize—but it would be possible.)

Moreover, we can certainly recognize why those in developing countries, with massive problems of poverty, disease and even starvation, seek the same economic engine of sprawl that we in the United States exploited in the post-war years—and we can certainly recognize why we are not in a morally superior position to deny them the same benefit. Instead, we, and they, need to work together to develop a more benign form of urbanization, along with a more positive form of economic growth and human development for the future.

Lessons for a New Urbanism

This brings me to the final problem, and here I must offer criticism of some of my New Urbanist colleagues. The original ideals of the New Urbanism ring through in the Charter. The mission was very clearly focused on changing the patterns of settlement, and most particularly of sprawl, as a responsible act of professional reform. Again, we recognized that these patterns didn't just happen—weren't just a function of market forces, natural technological evolution, or human desire for happiness in a perfect vacuum, as some still wrongly claim. These patterns were the direct result of theories about what cities are and should be.

All the elements of sprawl—functional segregation, mobility around the car, the end of streets as public spaces, the end of the compact walkable fabric of cities, etc.—were articulated in the 1933 CIAM Athens Charter, and the relentless indoctrination campaign that followed, at the 1939 World's Fair and elsewhere. This was a global regime, with hugely consequential results in localities around the globe. We are called on now to also think no less globally, and act no less locally, toward its reform.

Climate change is certainly one major dimension of this urban reform, as urbanism is one major dimension of climate change. But let us be clear: there are many other aspects of well-being and sustainability at stake, and many other elements at play in the vastly complex systems in which we live. That fact doesn't make us helpless, or mean that we are no longer responsible. It does challenge us to think and act more effectively about what Jane Jacobs called “the kind of problem a city is.” (As many will recall, she called it “organized complexity.”)

But for some New Urbanists, it seems to be time to retreat—into cozy boutique enclaves, or paralyzing prophecies of doom, or much narrower kinds of USA-focused projects that are imagined to be commendably modest. May I have the temerity to suggest they are only lacking in joined-up vision, not to say courage.

In the end, I think it is a simple issue of professional responsibility: for our responsibility as planners and architects is nothing less than to fix what our professions broke. That this system started in the USA does not mean that its pernicious effects remained there—or that its reform can remain there.

But in their defense, New Urbanists have been traumatized. There has always been a bit too much of the planner's command-and-control instinct at work, and if we cannot, like King Canute, command the waves of climate change away, then it must all be hopeless—and perhaps we must just make ourselves as comfortable as possible while we await the apocalypse.

But this postmodern nihilism is at once giving the threat of climate change too much importance, and too little. Although climate change is far from the only challenge we face (again, we must also add resource depletion, ecological destruction, contamination, nuclear proliferation, cultural erosions, and a host of other existential threats) this seminal threat may still offer us very helpful and instructive lessons. For climate change is the ultimate “whole-systems problem,” requiring us to understand how complex, dynamic, and unpredictable are the systems we deal with—and that includes cities, human technologies, and human economies. When we address emissions reduction to slow the destruction of climate change, we address many other issues of well-being and sustainability as well. (Including the requirements for adaptation to its effects, which are more related than the dualistic debates between “adaptation” and “mitigation” assume.) There is little to lose, and much else to gain, by taking a “whole systems” approach.

So we would do well to have more humility, when it comes to both the positive and the negative possibilities of the future. More to the point, we would do well to stay focused on our task, to find intelligent and dynamic responses to our challenges (including self-made ones) wherever they may emerge. In that context, it is not helpful to make absurdly specific prophecies of doom based on the sensationalism of selective media accounts, and bogus claims to “what the science says.” On the contrary, when it comes to predicting future scenarios with certainty, “the science” (which I learned a good deal about in my dissertation research) says, and can say, no such thing. Such certain-sounding predictions are punditry, not science. And as Hans Rosling and others have helpfully pointed out, this punditry plays into an unhelpful cognitive bias toward negativity, paralysis, and self-fulfilling prophecy. If we think we're doomed, we might just make ourselves so.

To be sure, life is a dangerous, uncertain and complex business—and always has been. The aim of planning and design is not to eliminate the threats, which is usually impossible, but to learn to manage them, by learning how to engage with their dynamics. In the case of sprawl, we must learn to operate the levers of the “operating system for growth,” and find more economically and technologically viable alternatives. We have already made impressive progress on code reform, market and economic incentives, professional models and standards, and many other areas—though there is much work remaining. We have partnered with others in other fields to begin to reform economic feedback systems, to develop digital technologies for smarter urbanism, and to create interdisciplinary reform frameworks like the New Urban Agenda. This landmark international document in many ways mirrors The Charter of the New Urbanism, and marks significant progress for our movement. The ultimate aim of all these joined-up efforts is a transition not only to smarter cities, but to a smarter kind of civilization—since, as always in human history, we must get smart, or die. I prefer the former.

For us as urbanists, there are a number of major challenges remaining. One of the most important is to avoid focusing too much attention on the existing walkable mixed-use places, usually in the historic cores of cities. This over-focus on the relatively small cores is often meant to address affordability, equity and sustainability—but as sad examples like Vancouver show, it actually results in the opposite, only fueling runaway costs, gentrification, displacement, and unsustainable sprawl. And if we are honest, we will admit that it uglifies and degrades the best parts of our cities, leaving the worst parts as larger unaddressed problems, while making a few of us wealthier. We must focus instead on creating beautiful new walkable, transit-served, low-emissions, high-livability places for a diverse population, within diverse, polycentric regional systems—including suburbs. (I am gratified to see this as a theme of the 2019 conference in Louisville—but again, let us think globally as we act locally.)

We are not powerless. We do have power, and responsibility—but in different forms than we might imagine, many of them as yet undiscovered. Let us get our eye back on the ball—the pathological forms of sprawl—and finish what we came to do.