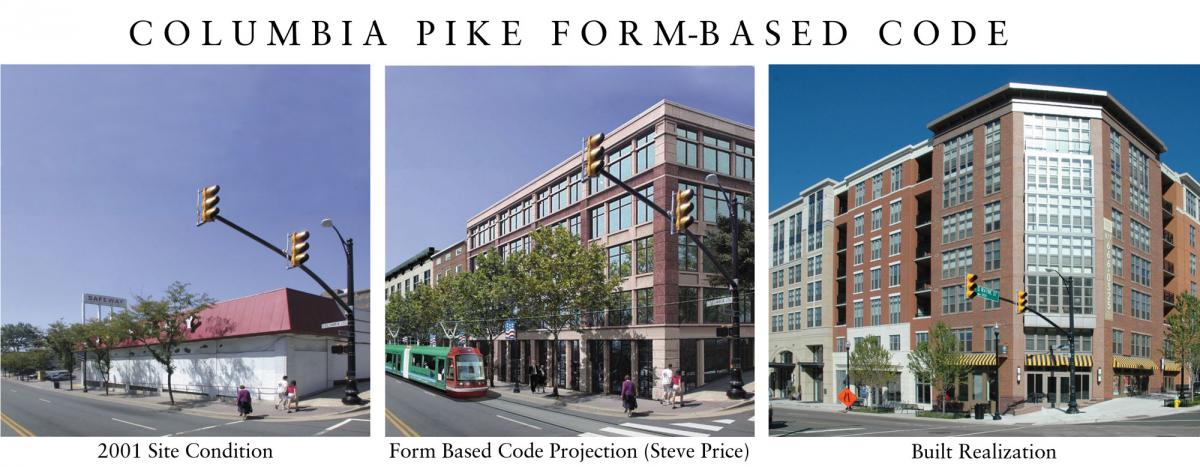

Twenty years of retrofit with a form-based code

On September 28th, the CNU DC | Mid-Atlantic Chapter of urbanists held a 20-year review and walking tour of the form-based code (FBC) for a former 3.5-mile strip-commercial portion of Columbia Pike in Arlington County, Virginia. The Pike aligns with the Pentagon, which employs 26,000 military personnel and civilians. It is a significant commuter and bus route to this destination. This is one of many congested streets and highways that serve Northern Virginia commuters heading northeast to Washington, DC, and Maryland.

The Pike had been littered with auto-oriented strip shopping centers and has not seen any positive transformations compared to neighboring areas and countries. The lack of Metrorail service is a primary reason, as its location is between four transit lines. After reviewing the Metrorail service map, it is clear that this section of northern Virginia needs a rail line in the network. Conversely, the areas accessible by Metrorail have seen robust transit-oriented development. Without that asset, the Columbia Pike corridor had remained the same for several decades.

Tim Lynch, Executive Director of the Columbia Pike Revitalization Organization (CPRO, now CPP), took on the challenge of changing the underutilized and disinvested environment. After reading Suburban Nation, he engaged the extraordinarily diverse and international population, as indicated by school children speaking over 60 languages. Community input for the vision was a first step. He convinced the County to hire a team led by Dover Kohl & Partners, with Geoffrey Ferrell Associates, to develop a master plan and form-based code to foster mixed-use, transit- and pedestrian-oriented infill redevelopment for four nodes at crucial intersections along the Pike. The code distinguished the setback, height, and form by streets: mixed-use commercial, transitional, and residential.

Due to the immense length of the corridor, development could have been faster, less opportunistic, and consequently unfocused yet encouraging. Under the leadership of a handful of CPRO and Columbia Pike Partnership’s (CPP) executive directors (who participated in the review), the last two decades have seen over 3,400 residential units built—of which 900 affordable units were committed to residents earning up to 60 percent of Average Mean Income (AMI). More than 350,000 square feet of commercial space, a 53,000-square-foot community center, three new plazas/squares, mini parks, and new grocery stores have been completed.

Matthew Bell and Michaela Mahon, Board Members of CNU DC | Mid-Atlantic Chapter, moderated the presentations and panel discussion. Speakers and panelists included:

- Andrew Schneider, Executive Director, Columbia Pike Partnership.

- Geoffrey Ferrell, founding member of the Form-Based Code Institute.

- Lauren Riley, land-use and zoning attorney, Walsh, Colucci, Lubeley & Walsh.

- Timothy Lynch, past Executive Director of Columbia Pike Revitalization Organization.

- Takis Karantonis, Vice-Chair, Arlington County Board, past Executive Director of the Columbia Pike Revitalization Organization.

- Matt Mattauszek is the planning Coordinator for Crystal City and Pentagon City and an advisor to ensure the adopted vision for Columbia Pike.

- Christopher Gordon, Principal, KGD Architecture.

- Dhiru A. Thadani, President of CNU DC | Mid-Atlantic Chapter.

The morning began with an introduction to the FBC and an orientation to and history of Columbia Pike and its community. The two former CPRO Executive Directors, Takis Karantonis, (currently a County Board member) and Tim Lynch shared their insights, pros, and cons on administering the FBC. During his tenure from 2000 to 2006, Tim was instrumental in the FBC adoption by the Arlington County building/planning code department and ushered in the first projects under the code. Both former Executive Directors spoke eloquently about the ethnic diversity of the community and a large percentage of resident participants who vocalized their desires, made drawings of their vision, and subsequently took ownership of the plan and its FBC.

Geoff described the FBC and led a walking tour following the introduction. He shared numerous insights related to streetscapes, buildings, and civic spaces built under the FBC. He noted areas where it had been a learning experience that produced modifications, noting that greater interaction by all involved would likely produce subtle but useful changes.

After our tour, wrapping several blocks on both sides of the Pike near our venue, and lunch, the panel discussion's conclusions affirmed the FBC's significant advantages to developers and the County approval process. Chris Gordon noted that the FBC, independent of its technical merits, diminished the risk and cost for the developer. He and Lauren Riley contrasted the FBC approval process with the standard 4.1 process by the County, which requires a multi-stage series of reviews, often by different groups of people, thus far more discretionary and time-consuming. The standard process included a site plan, smart community, energy reviews, and other milestones. Lauren mentioned public and county staff and board reviews, which are more discretionary and produce less reliable outcomes, requiring more revisions and higher costs. Getting a permit under this county process has sometimes taken six years.

Chris added that the 4.1 process cost could be as high as a million dollars and take years. He said that these costs would be the same for a 50-unit building as they would be for a 200- or 500-unit building, which explained that the projects that have gone forward have been on larger sites, with smaller sites attracting little or no interest. The bigger buildings spread the costs over more units.

These realities helped explain the larger projects that have been built. The FBC process provided more predictability and reassured the development community of a much shorter timeline—about one year for approval, and therefore less front-end cost. The consensus was that architects, administrators, and developers on the Pike much preferred Geoff's form-based code process as a customized tool for the corridor. It is closer to a by-right scenario. In the FBC approval process, the development team, aided by an architect and land use attorney, could meet with the county planners to determine the requirements and timeline. If those requirements are met, they cannot be denied approval.

Geoff stated that the primary goal and emphasis 20 years ago was improving the street experience. There is an overall plan for the entire corridor that eliminates the guesswork and builds coherence of what might be built in the future. Geoff expressed frustration with the sparseness and sporadic street trees and their inadequately sized planter areas. Street trees should form a continuous sidewalk-shaded area and give greater cohesion to the entire corridor.

Matt Mattauszek’s delivered an overview of the 20 years since the code was enacted, and noted that the primary emphasis was to get buildings built quickly on vacant or underutilized land. That priority meant less scrutiny of building design and material quality. Two decades later, some question why buildings constructed on the Pike do not meet current sustainability criteria. Today, the FBC is one of many more requirements it competes with (energy audits, tree canopy, ecology, and biophilic design). Given the existing condition of Columbia Pike, he praised the FBC as the only customized tool that could work on the corridor.

Michaela Mahon raised the issue of the changing retail landscape. Lauren replied that even before COVID, retail was struggling. She added that recognizing the lack of demand for retail spaces, the County has become more flexible regarding what uses are permitted at the street level, helping fill retail while maintaining storefront-like transparent surfaces.

Michaela suggested that, in hindsight, it may have been better to consolidate development in one node rather than all four, a proposal that many agreed with. Matt Bell suggested the similarity with Connecticut Avenue as a model where retail and services only occur at the former streetcar stops, now Metro station, with inline apartment buildings between nodes.

Dhiru Thadani remarked that appeasing through-traffic commuter automobiles and creating a walkable environment are incompatible goals. He suggested narrowing the road to three lanes at each node from five existing lanes to achieve walkability. Narrowing lane width to 9- or 10-feet would also tame traffic speed. I had follow-up discussions with Geoff, in which he spoke about efforts and considerable research on the positive aspects of reduced lane widths, which led to reduced traffic speeds and excellent safety. However, he also felt the well-informed transportation engineers had narrowed the lanes as much as they felt was possible.

Geoff also remarked on the challenges of long-term city planning versus short-term developer interest to maximize profit, benefit from tax depreciation laws, and sell the property within a decade or even less. This practice resulted in the near impossibility of convincing the development community to build buildings that last a century or more. Chris suggested that the underwriters could apply the necessary pressure to have long-lasting buildings designed with far less specific use requirements. Buildings that could be more readily converted to different uses. This problem—rigidity of highly specific use buildings (not unrelated to similarly narrow and specific use zoning) is presently seen in the abundance of vacant office buildings that are difficult to convert to residential uses for multiple reasons.

I immensely enjoyed the day. It was a great re-introduction for me to these issues with an in-progress tour and a panel discussion that included multiple viewpoints and engagements and was thoroughly representative of the complexities involved in these renewal efforts. Columbia Pike is an important ongoing model illustrative of much the best of community engagement processes and a continuous assessment and adjustment of the pros and cons of form-based coding in these quite common circumstances in our cities.