Complete streets: What went wrong?

The term “complete streets” was invented by staff members of national bicycle and smart growth advocacy organizations in 2003, and it was brilliantly effective in terms of moving legislation. Complete street policies have been the most adopted category of laws impacting transportation and the built environment in modern times.

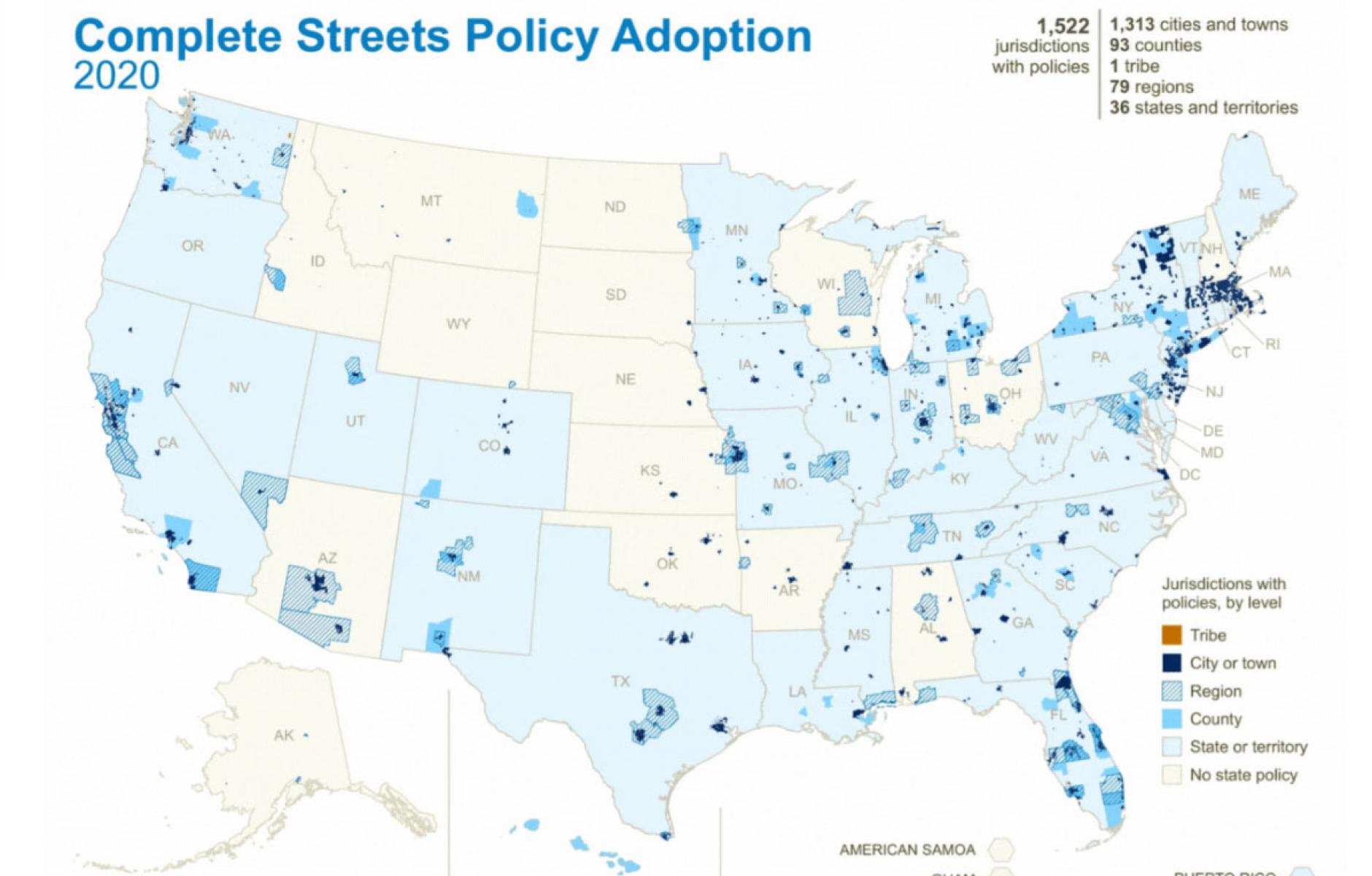

Complete streets policies have been approved by 37 states, plus DC and Puerto Rico, and more than 1,700 local jurisdictions in the US, covering well over 200 million people. Most major cities are covered by both state and local complete streets policies. Moreover, the federal government provides technical assistance for state and local governments to pursue a complete streets agenda, and the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides funding for complete streets.

The National Complete Streets Coalition (NCSC), part of Smart Growth America (SGA), defines complete streets as “streets for everyone. Complete Streets is an approach to planning, designing, building, operating, and maintaining streets that enables safe access for all people who need to use them, including pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists and transit riders of all ages and abilities.”

Tauro Law Center Professor Michael Lewyn explains, "Even though the term ‘complete streets’ was initially designed to address the needs of cyclists, it has been expanded to address pedestrian-oriented policies such as new crosswalks and improved sidewalks. These policies have four major justifications: safety, public health, environmental protection, and social equity.”

Lewyn has written, for the Indiana Law Review, an important overview of the complete streets movement called Incomplete Streets. For an article that takes up more than 30 pages of a legal academic journal, it is remarkably readable and jargon-free, tackling a topic important to the built environment. (Disclosure: Lewyn says the idea for the article came from my suggestion during a CNU session that he write about complete streets. Professor Lewyn deserves 100 percent credit for embarking on this journey and seeing it through.)

The complete streets movement was launched because American streets were dominated by automobiles in the early 2000s. More than 20 years later, that reality is unchanged. As Lewyn reports in 2024:

“American streets are typically made for automobiles. Some streets are as many as six or eight lanes wide. Such wide streets are difficult for walkers to cross, and motor vehicles frequently travel at speeds as high as 50 miles per hour—speeds high enough to kill a walker if a collision occurs. Even in urban areas, many streets lack sidewalks, forcing walkers to walk in the road. Separate lanes for cyclists are even less common than sidewalks. For example, Philadelphia has more bike lanes per square mile than any other US city, yet only 16 percent of its streets have bike lanes.

“The status quo has a wide variety of social costs. In 2022, over 7,000 pedestrians lost their lives in crashes with automobiles.”

Pedestrian deaths, which have risen 75 percent since 2010, are the strongest evidence of the failure of the complete streets movement. The movement's growth coincides with the carnage of people on foot across America, largely occurring on the wide, automobile-oriented streets that Lewyn describes. The other evidence of the failure is that little has changed in the 98 percent of metro areas built for getting around by automobile. One can drive around all day without coming across a thoroughfare that has been redesigned from drive-only to walkable.

That’s not to claim complete streets policies have had no impact whatsoever. The largest effect has been in core cities of major metro areas, some of which have built substantial bicycle lanes, sidewalks, and crosswalks. As Lewyn reports, “the number of American street-miles served by protected bike lanes increased from 34 miles in 2006 to 425 in 2018. Nevertheless, these improvements are quite modest since the US has over 2.8 million urban street miles. Sidewalk improvements have occurred in some cities, but at a slow pace. For instance, in Austin, Texas, which has a complete streets policy, voters approved a bond issue to add more sidewalks; the bond issue will only add sidewalks to 3 percent of the streets without them.”

What went wrong, Lewyn asks? The failure can be explained for two reasons. First, cities have limited funds to reconfigure streets. “To put a sidewalk on every street, Indianapolis would have to spend $7.2 billion, more than five times the annual budget.” This fiscal reality could change if complete streets were heavily funded by state or federal governments. However, this is not the case (despite the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which allocated 2.5 percent of funds toward complete streets). The second factor is probably more important: “The language of complete streets policies is often so vague as to justify almost any conceivable policy,” Lewyn explains.

NCSC and SGA have developed a 10-part Policy Framework to suggest the best quality complete streets laws:

- Establish a general vision

- Prioritize underserved communities

- Apply to all projects

- Have clear exceptions

- Mandate coordination among government agencies

- Adopt excellent design guidance

- Require proactive land-use planning

- Measure progress

- Set criteria for choosing projects

- Include plans for implementation

While that list is good in many respects, Lewyn is critical of the vagueness of how some of the recommendations are explained. “The Framework explains the spirit of complete streets policies by emphasizing that governments should consider the needs of non-drivers rather than focusing solely on encouraging ever-faster automobile traffic. But because the Framework is not always clear about how to achieve this goal, it does not guarantee meaningful change.”

Lewyn suggests that streets should be designed for lower speeds. “A pedestrian is unlikely to die when hit by a vehicle going 20 miles per hour (mph) and is likely to die when hit by a car going 40 mph. Thus, a complete streets policy should provide that streets likely to be used by pedestrians, like streets with residences or shops, should not be designed for any speed high enough to lead to death in the case of a collision.” He adds that complete streets policies should include a menu of specific options for achieving this goal, such as reducing the width of vehicle lanes to 10 feet or less. Furthermore, streets with housing or workplaces should sidewalks, and protected bike lanes.

Measuring progress should include meaningful data points, such as the number of streets with sidewalks and bike lanes and “street designs that slow automobile traffic to a safe level.”

One of the few signs of progress over the last 20 years has been creating some truly excellent case studies of well-designed complete streets. We have reported on these case studies on Public Square. Not all of them include protected bike lanes, but they do include sidewalks and greatly reduced design speeds. Here are seven examples.

If I were to add my critique of the complete streets movement, I would say that it put too much faith in setting legislative goals, and too little emphasis on changing the culture and practice of street design. I remember when New York State adopted its complete streets policy in 2010 and I announced this milestone to a committee of advisors to the county planning department. I was excited about the dramatic change that would ensue, and the rest of the committee was unconvinced that DOT would change at all. They were right, and I was naive.

Lewyn suggests changing complete streets policies to focus more on specific streetscape elements—design speed, sidewalks, and protected bicycle lanes. As traffic engineer Wes Marshall reports in his excellent recent book, Killed By A Traffic Engineer, the traffic engineering profession desperately needs reform, and nothing else will reduce pedestrian fatalities.

The complete streets movement must focus like a laser beam on reforming street design practice. In doing so, the movement could begin to realize its promise. Until then, US streets will be “incomplete.”

To download Lewyn's article, go here.