Promoting creative retrofit solutions

What do we do with the obsolete suburban retail properties and office parks multiplying across the US? Some states, such as New Jersey, are looking at legislative solutions to failing commercial sites, and trying to promote mixed-use and walkability, among other goals.

Legislation is not my forte, and it is tricky. The goals are straightforward: as the automobile-oriented commercial sites are redeveloped, we should promote mixed-use and walkability.

We do that because walkable, mixed-use places promote health, safety, and sustainability. This is backed up by research, as the links indicate.

At the same time, every suburban retrofit is a creative process involving unique geographic, economic, and regulatory challenges. Developers, designers, and public officials use their skills and creativity to deal with unique sites and situations that present individual problems. The creativity and the challenges should meet in the middle, to achieve a higher-quality solution for the site.

In some cases, the solution involves tearing down most or all of the buildings and starting from scratch—a blank slate. In other cases, the buildings will be retained, but there is still room to achieve mixed-use and improve urbanism.

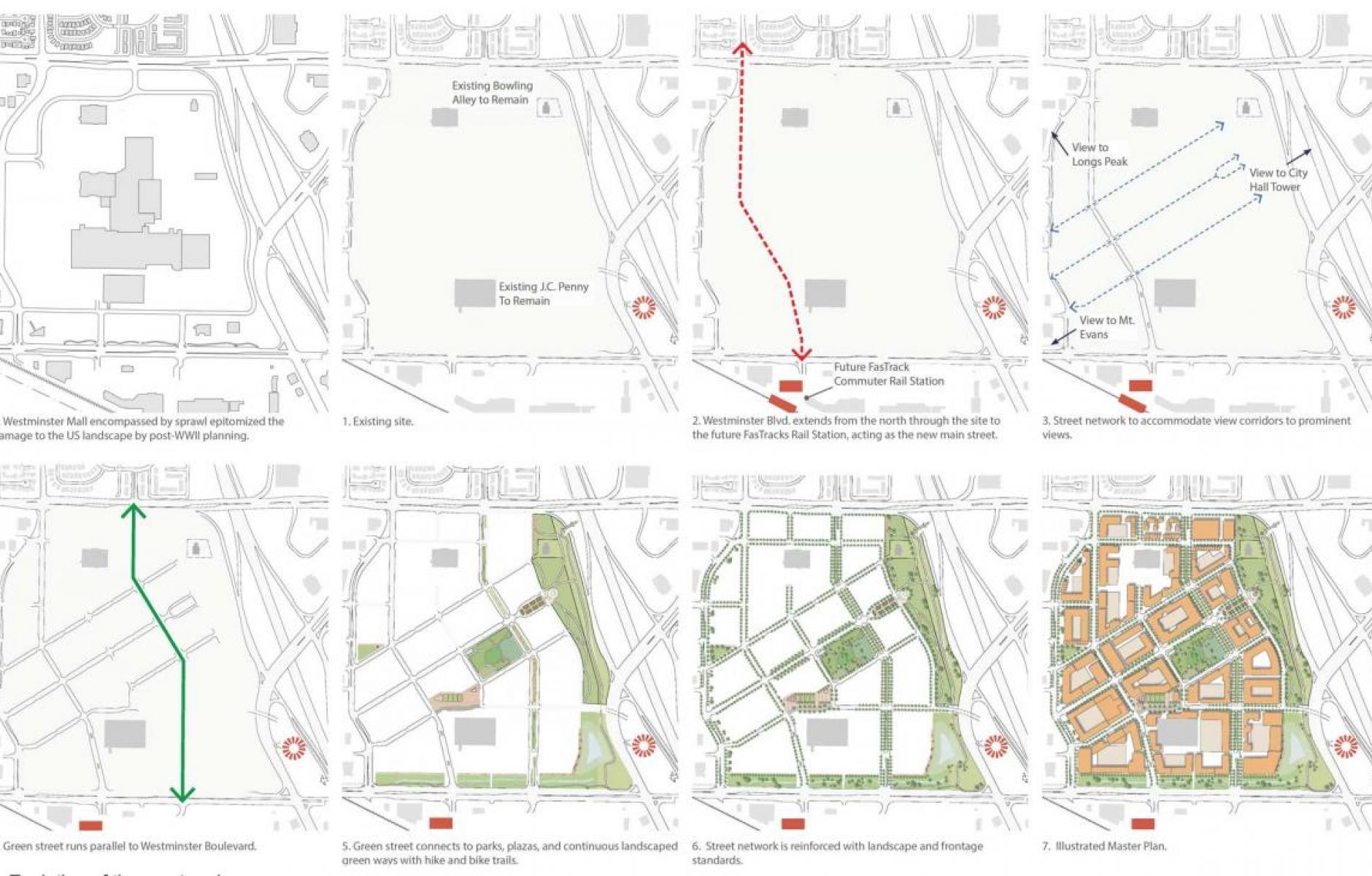

I have written about two projects that exemplify that choice—both offering creative solutions. The first is Downtown Westminster, Colorado, a 105-acre former enclosed mall site northwest of Denver (see plan at top). What many people don’t know about malls is that they frequently have many owners who control pieces of the site. The ownership lines are invisible except on legal documents, and they often hamper redevelopment.

Seeing that the mall was failing in the early 2000s—and it was an important contributor to city coffers—Westminster officials bought out the parcels over several years, except a JCPenney store and a bowling alley, which were eventually incorporated into a redevelopment plan. The city’s actions allowed the site to be replanned from nearly a blank slate—allowing for high-quality urbanism.

Downtown Westminster, designed by Torti Gallas & Partners, is only about a quarter built, but has already become a successful central gathering place for the city. The plan has a highly connected pattern of small blocks—measuring 355 intersections per square mile. For comparison, Rome, Italy, has 750 or more, but good walkable urbanism begins at about 150, according to Torti Gallas principal Neal Payton, who led the design team.

The plan has many excellent aspects, including how the grid was bent to provide views of Longs Peak and Mount Blue Sky (formerly Mount Evans)—the Rocky Mountains in the distance. Despite the dense, mixed-use development, the plan includes many great open spaces and a connection to a long-distance trail network. People living in Downtown Westminster, including those occupying the 20 percent affordable housing, will have a better chance at health than those living in drive-only neighborhoods.

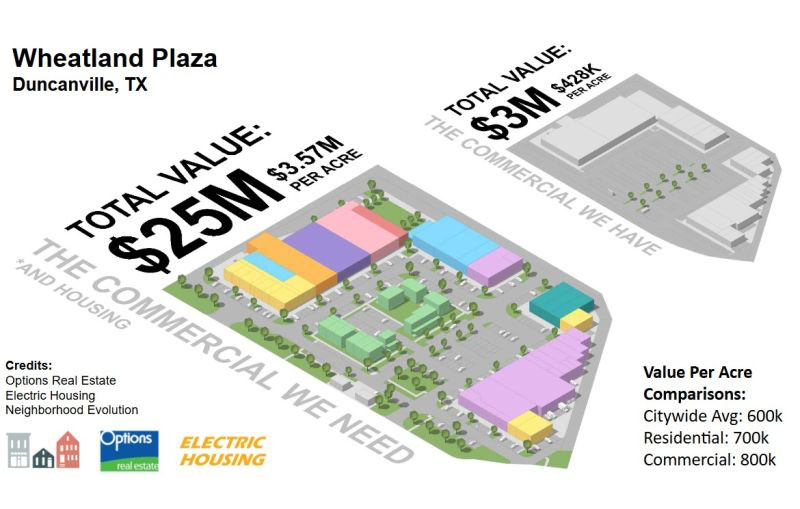

In Westminster, more than 90 percent of the mall was torn down. At the other end of the spectrum is Wheatland Plaza in Duncanville, Texas, a failing strip mall. Half of the storefronts were empty and the site value was low, yet economic and site conditions led to a far different strategy. In Duncanville, the developer chose to retain all of the existing buildings. The retail sites were divided into smaller, more flexible spaces.

The large, underutilized, inefficient parking lot was replanned to build five residential buildings and a small public square. A central drive lane was turned into a street, with buildings on one side, parking, and more trees. Despite keeping all retail buildings, the site is broken down into smaller pieces. There’s a new street, a residential block, and a square—the beginnings of urbanism.

Wheatland Plaza represents a more incremental approach that is more feasible for some sites and developers who don’t have the deep pockets of Westminster, a suburban city of 116,000.

The point is that both projects were led by teams that used considerable skill, knowledge, and design creativity to overcome unique sets of challenges and achieve a higher-quality outcome than existed before. They were guided by principles of urbanism—to make a place more diverse and walkable.

Getting back to the original issue, how do you legislate creative solutions to dying, single-use suburban properties? I think legislation needs to get rid of barriers: The zoning should allow a wide range of uses rather than single-use. Parking mandates should be reduced or eliminated. The setbacks should allow for urban buildings close to the streetscape, etcetera. At the same time, there should be incentives to do the right thing, but light on mandates that would prevent creative incremental solutions like Wheatland Plaza.