New land-use codes may transform communities but are notoriously difficult to communicate. They involve abstract concepts that nevertheless impact local health, economy, sustainability, and the built form over decades—in ways that are not always obvious to citizens or political representatives.

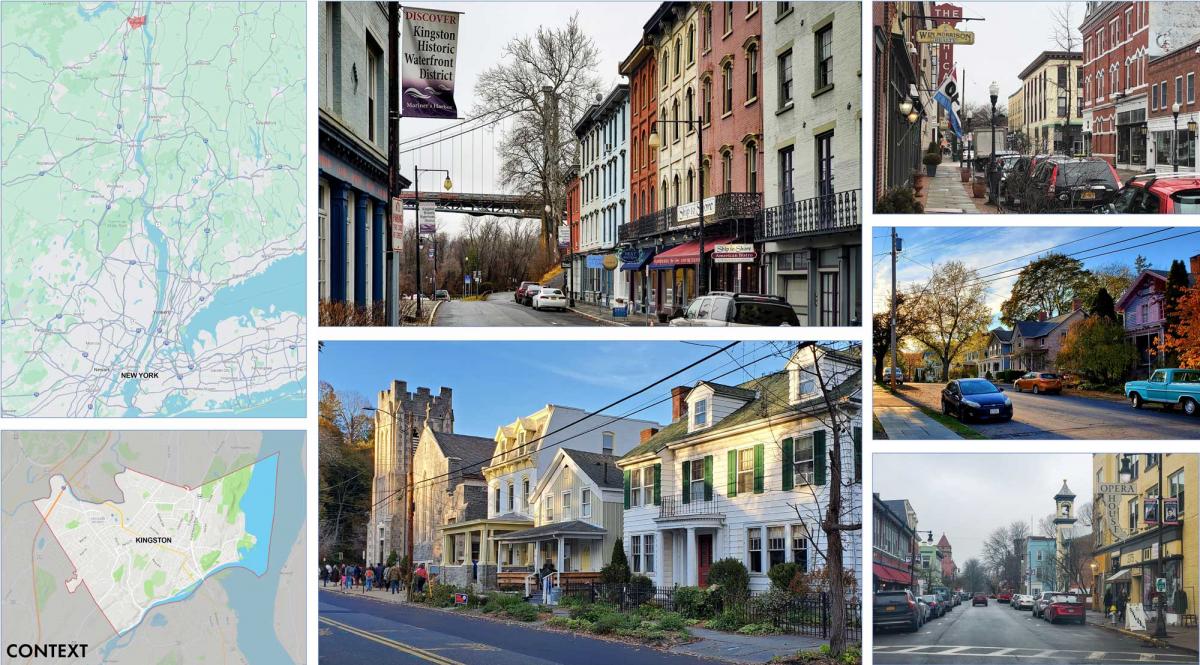

Kingston Forward is a state-of-the-art form-based code (FBC) adopted in August 2023 in a small Hudson Valley city that uniquely communicates the value of this regulatory reform. On a substantive level, Kingston Forward removes barriers to new housing—particularly missing middle types—and enables the reuse of historic structures. Like most traditional cities, Kingston, New York, was the victim of urban renewal that destroyed substantial historic urban fabric—while 20th-Century zoning codes made that fabric illegal to build anew. The new code legalizes the city’s traditional form while addressing important, current, housing needs.

“This new code is truly the vision of our community—it will encourage incremental growth and smart development across the City, while preserving our open spaces,” says Kingston Mayor Steve Noble. “Crucially, this code reform will reduce barriers to the creation of new housing at every level and will help us combat the housing crisis.”

According to the design team, the Kingston FBC supports best practices in housing, development, preservation, and environmental policy in the following ways:

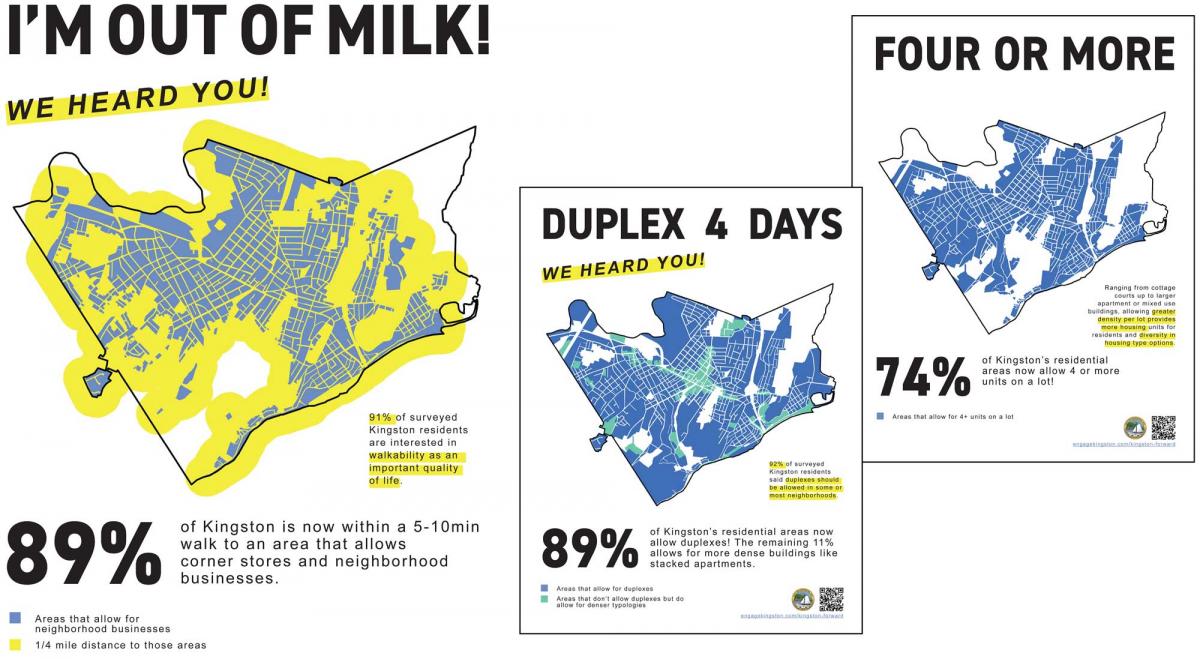

- It legalizes multifamily development citywide, including “missing middle” housing types, to encourage economic diversity and incremental development;

- Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) are legalized citywide;

- Corner stores are allowed within walking distance of most (89%) of homes;

- It removes citywide minimum parking requirements (maximum requirements are included);

- Form-based standards ensure that new development contributes to the city’s historic form;

- Adaptive reuse of existing buildings is encouraged by removing common barriers such as limited permitted uses and minimum parking requirements;

- Code metrics are improved: minimum lot sizes are removed and contextual setbacks are introduced;

- A permitted uses table and reduced number of districts simplify the use of the code;

- Mandates and incentives for affordable housing are introduced;

- The 500-year floodplain is adopted as local design flood elevation (DFE);

- Context-based complete street standards are included;

- Approvals are streamlined with a new Minor Site Plan process.

Each of these aspects requires an explanation strategy. “Zoning reform can be a technical subject; the City team made extra effort to make issues real and understandable to an average community member, so they could have informed opinions and provide input,” notes the design team. An enthusiastic endorsement by citizens and leaders can be attributed to an engagement process that elicited strong and genuine input through in-person and virtual workshops, walking tours, open houses, and on-site planning studios.

Zoning reforms can get stalled by a number of specialized issues, but Kingston’s leaders and community enthusiastically endorsed the new code, leading to unanimous approval by Common Council. That outcome is due to the messaging and engagement that allowed genuine input and opportunities for interaction with the City staff and planners, the team notes.

“Community ideas shaped the content of the code, creating advocates that later spoke in support of adoption,” the design team explained. “Kingston is the most socioeconomically and racially diverse community in the County. The City and reform advocates were able to show how the new code could benefit everyone. Presentations explained what code provisions for parking, setbacks, ADUs and greater mix of housing types and uses could mean for residents, homeowners, small business owners, and developers. Further, many of the code’s standards legalize historic development patterns and mix of uses; presentations focused on explaining why these code changes were important to preserving and enhancing Kingston’s traditional neighborhood form.”

The code provides an example for other cities to follow, argues to Jolie Milstein, President and CEO of New York State Association for Affordable Housing. “With its new zoning code, Kingston is leading the state in pro-housing land use reform,” she says. “This new zoning code will directly enable the development of affordable housing while respecting Kingston’s historic character.”

Similar Projects

RiverFront Revitalization

Omaha, Nebraska

The RiverFront Revitalization in Omaha, Nebraska, makes a unified, transformative, 70-acre civic-oriented park at the center of a major city in the nation’s heartland.

Trappey and Bayou Vermilion Waterfront District Vision Plan

Lafayette, Louisiana

For three decades, the vacant Trappey cannery on the Vermilion River deteriorated, but thanks to community stakeholders, private developers, and the City of Lafayette, this prime site will become a new neighborhood.