When freeways have no futures

Freeway construction was a disaster for city neighborhoods in the 20th Century. Many neighborhoods were divided in two—their main streets demolished and businesses closed, disproportionately in minority communities. The African-American Tremé neighborhood in New Orleans is a good example, as the elevated Claiborne Expressway was built in the 1960s over Claiborne Avenue, a boulevard with a central green space that served as the commercial heart of Tremé. Claiborne Avenue was never the same.

Many freeways built through cities are unnecessary. After San Francisco’s 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, for example, the Embarcadero and Central freeways were damaged beyond safe use. Traffic disasters were predicted when they were closed, but failed to occur. Boulevards replaced the freeways instead, opening up the waterfront and uniting neighborhoods in the City by the Bay.

After 2000, a few cities voluntarily tore down sections of freeway—and found their economies and tax bases rising and the urban fabric healing. Planners and citizens relearned the power of the street grid to support multi-modal traffic, economic development, and city living. The first CNU biennial Freeways Without Futures, published in 2008, charted these early restoration efforts, with subsequent reports in 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2017.

As this decade comes to an end, cities and their freeways are at a crossroads. Limited-access highways that were built through cities in the 1950s through 1970s are now at the end of their useful life, and cities must decide whether to rebuild. Replacement with a boulevard or a grid of surface streets is usually cheaper and may offer significant social and economic benefits. So far, 15 North American cities have either removed or committed to remove or mitigate their freeways. A national movement to replace unnecessary sections of freeways with surface streets has taken hold among city leaders, citizens, and transportation planners.

Freeways Without Futures 2019 is the tale of ten freeways in cities coast to coast where this movement has spawned active campaigns for transformation. These freeways are:

- Claiborne Expressway (I-10), New Orleans, Louisiana

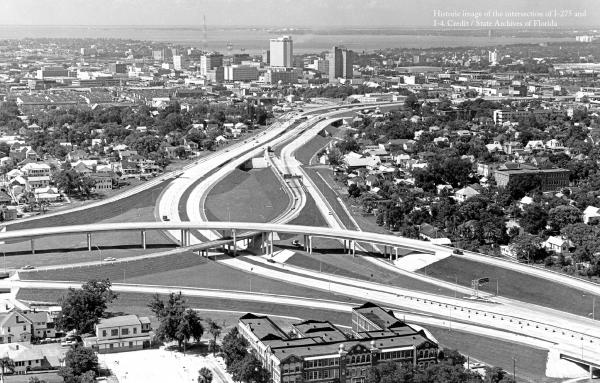

- I-275, Tampa, Florida

- I-345, Dallas, Texas

- I-35, Austin, Texas

- I-5, Portland, Oregon

- I-64, Louisville, Kentucky

- I-70, Denver, Colorado

- I-81, Syracuse, New York

- I-980, Oakland, California

- Kensington and Scajaquada Expressways, Buffalo, New York

Here are the fundamental questions that these campaigns raise: Do we continue to funnel billions of taxpayer dollars into an aging system that pollutes cities, divides neighborhoods, and occupies valuable land that could instead be used for homes and businesses? Or is there an alternative solution that creates stronger cities and communities?

The pace of urban freeway removal is accelerating. Three cities—Detroit, Rochester, and Seattle—have begun to dismantle their freeways since 2017, the year of the previous edition of Freeways Without Futures. This acceleration reflects widening acceptance that the great age of in-city highway construction is effectively over (the Federal Highway Administration declared the Interstate system complete in 1992), and an increasing support for highway transformation among local and state governments. In selecting projects for this report, we noted the strong presence of city council people and mayors who are engaged in or formally endorsing highway removal campaigns. Some candidates for office are even campaigning on the issue.

The diversity of cities undertaking these projects is also noteworthy. This is not a movement confined to any one geographic region, nor limited only to larger cities or those that are experiencing immense growth. Small and mid-sized cities like Milwaukee, Somerville, Niagara Falls, Chattanooga, Detroit, and Rochester have opted to measure community progress and quality of life by a set of metrics other than travel time: economic reinvestment and increased tax revenue; the creation of walkable streets and new public space for the community; and gains in public health, air quality, water quality, and climate resilience.

Economic gains

When the Interstate system and other state highways first encroached on cities, they converted valuable land in the heart of downtowns and along waterfronts into clogged arteries of traffic that produced virtually no direct income for local economies. Cities that choose to remove urban freeways have an opportunity to reclaim this real estate to help fulfill the increased demand for walkable, urban living. Reclaiming the land underneath highways can boost and stabilize city populations, providing direct local control of land that can be dedicated to a range of housing choices for individuals and families, from affordable housing below market to workforce housing and flexible choices for young renters and older “empty nesters.” Highway removal is a once-in-a-generation occasion to revitalize downtowns, neighborhoods, and waterfronts and strengthen local economies.

A vibrant public realm

Highways fall flat in this metric, with negative rather than positive outcomes. Few people enjoy walking underneath a highway, let alone spending time around it. On the opposite end of the spectrum, streets and public spaces dedicated to people, not cars, offer members of the community places to relax, shop, and enjoy each other’s company in public. Places like these were destroyed to make way for freeways. Now, the opportunity presents itself to create a new, vibrant public realm for the communities that bore the brunt of highway construction. A city’s public realm exists in its public spaces, the streets and squares that integrate individual buildings into a coherent urban unit. When properly designed, the space between buildings promotes a strong public life and contributes to the civic character of the city.

A healthy environment

Choosing city streets over freeways means leaving behind the hazards of highly concentrated vehicle exhaust near residences, businesses, and schools. Many urban highway segments run through the densest parts of their cities, exponentially increasing the number of people exposed to toxic fumes and particulates from cars and truck traffic. Known health risks from proximity to highways include increased rates of respiratory ailments and cardiovascular illnesses. Extensively overbuilt highway infrastructure encourages even more driving and perpetuates these conditions. This brief overview does not even take into account noise or the impact of being stuck in traffic, both of which are health hazards.

The removal of a highway is not a silver bullet for every urban issue, but it is more than a simple transportation or infrastructure problem. It intersects with community health, fiscal responsibility, and equitable urban development. Cities that choose alternatives to highways have decided to prioritize people over vehicles and to address needs that have been underdeveloped in favor of automotive mobility.

This preference for automotive mobility almost always came at a cost to the communities in its path; African American and other minority communities were especially hard hit. Yet even during the Great Age of the Highway, many highway construction projects stalled and were never completed due to community opposition. Famous examples include the opposition of Sammie Abbott and Reginald H. Booker to the construction of a highway through Washington D.C.’s mostly minority neighborhoods at that time, and the confrontation between Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses over the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have cut a swathe through modest-income and ethnically diverse Greenwich Village.

This does not mean successful highway construction went forward unopposed. Many minority communities that now live in the shadow of highways originally fought bitterly and bravely against them; the descendants of those protesters continue to fight to protect and strengthen what remains of their community design and opportunities. The benefits of highway removal must acknowledge the profound need to make reparations in communities that were so disrupted—many of which have persisted nonetheless. Cities need to ensure that both the social and economic value unlocked by dismantling a freeway is channeled to serve its long-standing members of the community.

As cities consider what to do with their aging in-city highways, they should recognize the opportunities for freeway removal and transformation. As the ten projects in this report demonstrate, cities can save money while boosting their economies and improving the lives of citizens by not repeating the mistakes of the 20th Century.

Note: Freeways will be a topic at CNU 27 in Louisville June 12 through 15. Discounted registration is available until May 10th.