When is a highway cap appropriate?

In our previous coverage of Freeways Without Futures 2021, we looked at three ways to tame major highways. One possible solution is to cover the highway.

Highway caps, also known as lids, can be a contentious topic among urbanists. Critics argue that highway caps are little more than greenwashing, literally covering over the problems highways cause without addressing their source. Supporters of caps point out that the political will to remove highways doesn’t always exist and caps have the power to restore connectivity as well as create new urban space.

Freeways Without Futures 2021 tells the stories of several Highways to Boulevards projects that propose covering highways as a path to reconnecting communities. In Seattle, the Lid I-5 movement seeks to build on the legacy of Freeway Park and spark a citywide conversation about what can be done with highways that damage communities. In Austin, different coalitions are simultaneously developing plans for I-35, some to cap it, others to remove it, but all agree either solution would be better than the Texas Department of Transportation’s (TxDOT) proposed expansion highway. In Buffalo, the Restore Our Community Coalition (ROCC) has advanced a vision of the Humboldt Parkway restored, built on a cap over the Kensington Expressway. ROCC supports a cap because the New York State Department of Transportation’s (NYSDOT) plans for a ‘removal’ replaced the sunken expressway with a Humboldt Parkway designed for a 55 mph speed limit.

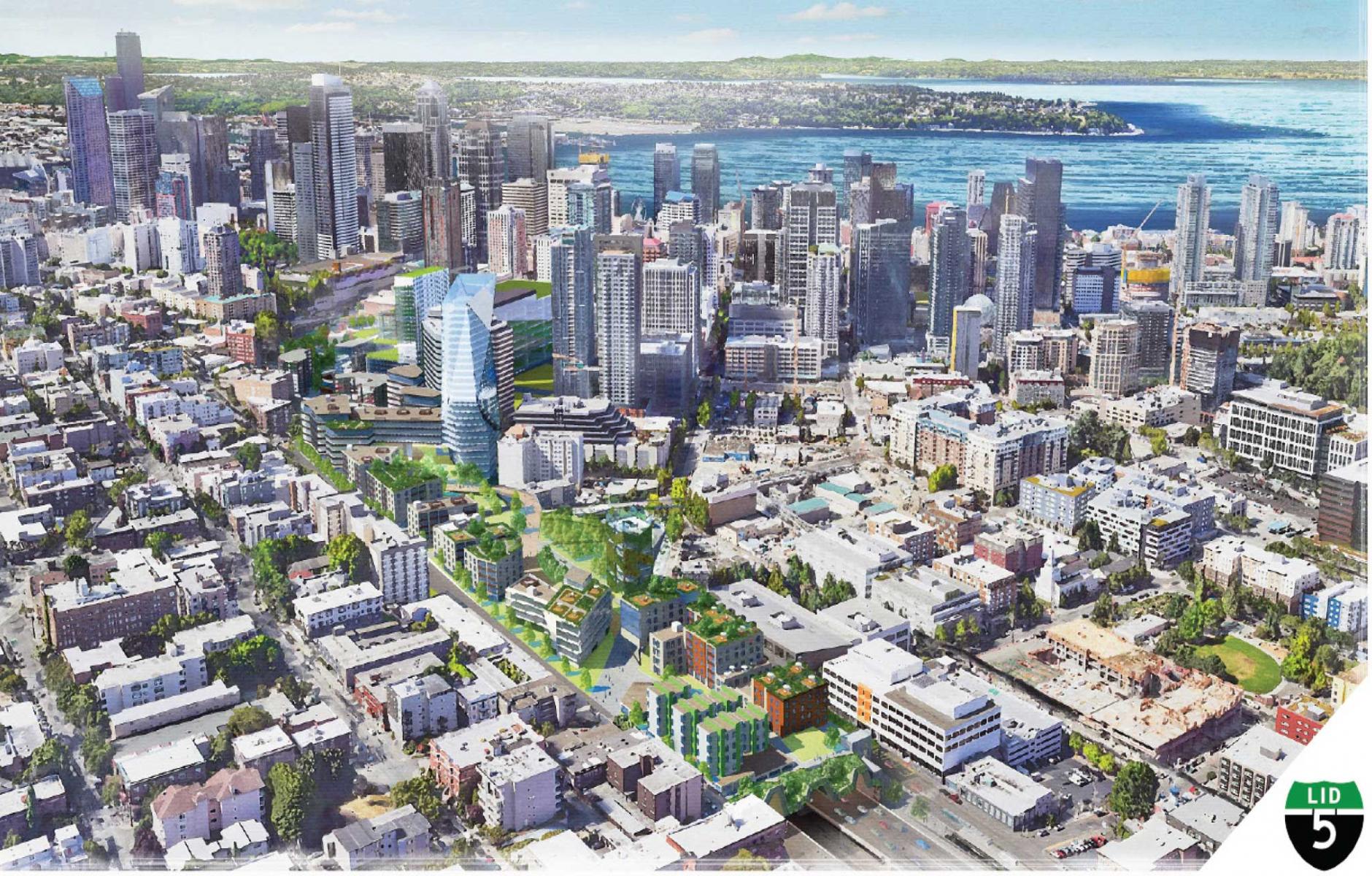

Interstate 5, Seattle, Washington

Early on, Seattle pioneered a new way of thinking about the relationship between city and freeway with the construction of Freeway Park over I-5 in downtown. Today, the highway is overdue for safety upgrades, including earthquake retrofitting, presenting the perfect opportunity to expand this lid and better serve people, not just cars.

Since 2015, the advocacy group Lid I-5 has sought to expand on the successful examples of lids and has worked with the public on new design concepts that could add another 17 acres of lid area over I-5. The group recognizes that an expanded I-5 lid can simultaneously address several of the pressing challenges Seattle faces. Downtown Seattle lacks sufficient green space, and the expansion of the lid could create more for the 40,000 people who would live only a 15-minute walk or less away. The same residents who lack easy access to green space are also concerned about displacement risks, which have increased in downtown since 2010. An expanded lid over I-5 could provide new land on which to build affordable housing in the heart of a diverse neighborhood with both a high displacement risk and high access to opportunity.

Rather than endorsing one particular concept for what gets built on top of the freeway, Lid I-5 remains purposefully flexible so that the greater community can weigh in on plans that can be calibrated to suit local needs. That opportunity is expected to be coming soon. The City of Seattle has taken an interest and recently completed a feasibility study for the project, which demonstrated that lidding more of I-5 is both technically feasible and potentially desirable, as it can significantly improve the quality of life for residents.

Everyone in Austin agrees that Interstate 35 doesn’t work. The highway was built to act as a chasm between downtown and communities of color in East Austin, and is the city’s most dangerous corridor for pedestrians. It is clear that in its current form I-35 serves no one particularly well.

TxDOT is adamant that there is only one solution for I-35’s woes: a $4.9 billion highway expansion to up to 20 lanes. This proposal hinges on traffic forecasts that opponents say consistently overestimates actual levels. A growing number of people realize that highway expansion induces even more demand for driving, which quickly fills up the newly-created capacity and leaves congestion as bad or worse. To learn this lesson, TxDOT needs to look no further than Houston, where traffic on the Katy Freeway, expanded up to 26 lanes in 2008, has only gotten worse since it was widened.

So, what else can be done for I-35? Local advocacy group Reconnect Austin has long pushed for a solution that keeps I-35 within its current footprint, depresses 3.4 miles of it (from Holly Street to Airport Boulevard), and covers it with a cap. On top of the cap, Reconnect Austin proposes a new boulevard consistent with Austin’s Great Streets Master Plan, which includes generous space for pedestrians, cyclists, and dedicated transit lanes.

Other groups in the area are also thinking about how to change I-35. In 2019, the Urban Land Institute report for the Downtown Austin Alliance proposed caps at several key locations to create blocks-long park spaces, similar to the Klyde Warren Park in Dallas. Another group, Rethink35, proposes removing 8 miles of I-35 altogether and replacing it with a boulevard that includes regional trains, bus lanes, protected bicycle lanes, and wide sidewalks and incorporates anti-displacement measures for nearby communities. Inspired by previous freeway removals, Rethink35 points toward climate change, traffic crashes, automobile dependency, and induced sprawl as to why I-35 should be removed.

All three of these coalitions recognize I-35 in its current form as a liability for Austin and seek different ways to create assets along the corridor that provide community benefits.

Kensington Expressway, Buffalo, New York

For over a decade, the Restore Our Community Coalition has campaigned for the restoration of the Humboldt Parkway, the Olmsted-designed street the Kensington Expressway replaced. Through their efforts, NYSDOT has come to the table. But the community has found NYSDOT’s alternatives less than acceptable, as they fail to include a true parkway or boulevard option.

In 2014, a group of Hamlin Park residents, the Restore Our Community Coalition (ROCC), launched its “I Remember” public awareness campaign. It combines historical archives, testimonies from past and present residents, and case studies from comparable projects in other cities to build a community-focused narrative for restoring a third of the original Humboldt Parkway. As a solution, ROCC proposes a green cover over approximately one linear mile, or 14 acres of the expressway’s imprint, from East Ferry Street to Best Street.

While some community members would like to see the expressway removed entirely, others are concerned that the NYSDOT would build a surface-level road with highway-like qualities as a replacement.

As an alternative, ROCC has rallied around the idea of a cap, which would still reap substantial benefits for the community. The 2014 Humboldt Parkway Deck Economic Impact Study projects that the restoration of the parkway will bring significant reinvestment to the Jefferson and Fillmore business districts that bookend Hamlin Park. In turn, this could generate up to $2.8 million in new property tax revenue for the City of Buffalo over a 30-year period, in addition to $76.7 million in household wealth.

In 2016, Governor Andrew Cuomo backed a $6m environmental impact study of different capping options for the expressway. But when NYSDOT unveiled the options in 2019, they were underwhelming at best, providing only limited connections across the highway and failing to reduce air or noise pollution. The presented alternatives were far from a parkway restoration. Renderings showed few street trees and placed an exaggerated ventilation facility at the end of the cap that resembles a factory with smokestacks. Critics suspect this was an intentional ‘poison pill,’ designed by NYSDOT to make the Humboldt cap seem unappealing.

As Buffalo continues to overcome past mistakes, it needs better solutions for this highway than what NYSDOT has proposed, ones that will bring long-term investments to the Hamlin Park community.

To learn more about the other highways in Freeways Without Futures 2021, download the report here.