A small ‘c’ conservative case for urbanism

Note: This article is a summary of talk given by Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns at an event that CNU co-sponsored a while back with The American Conservative. View the whole talk here.

No society in history has ever done what we have done: taken thousands of years of history and knowledge about how to make places, thrown it completely out, and done something completely and radically different, all within a short timeframe. We are in the midst of one of the greatest experiments of all time. And we are the guinea pigs.

Let’s start by thinking about the way cities were designed thousands of years ago. If we look at these places what we see immediately is that they were built around the dominant transportation technology of the day, which was your two feet. People walked everywhere, and so the scale, the spacing, the distances between things people would do on a normal day, all of this was based around a society of people who walked.

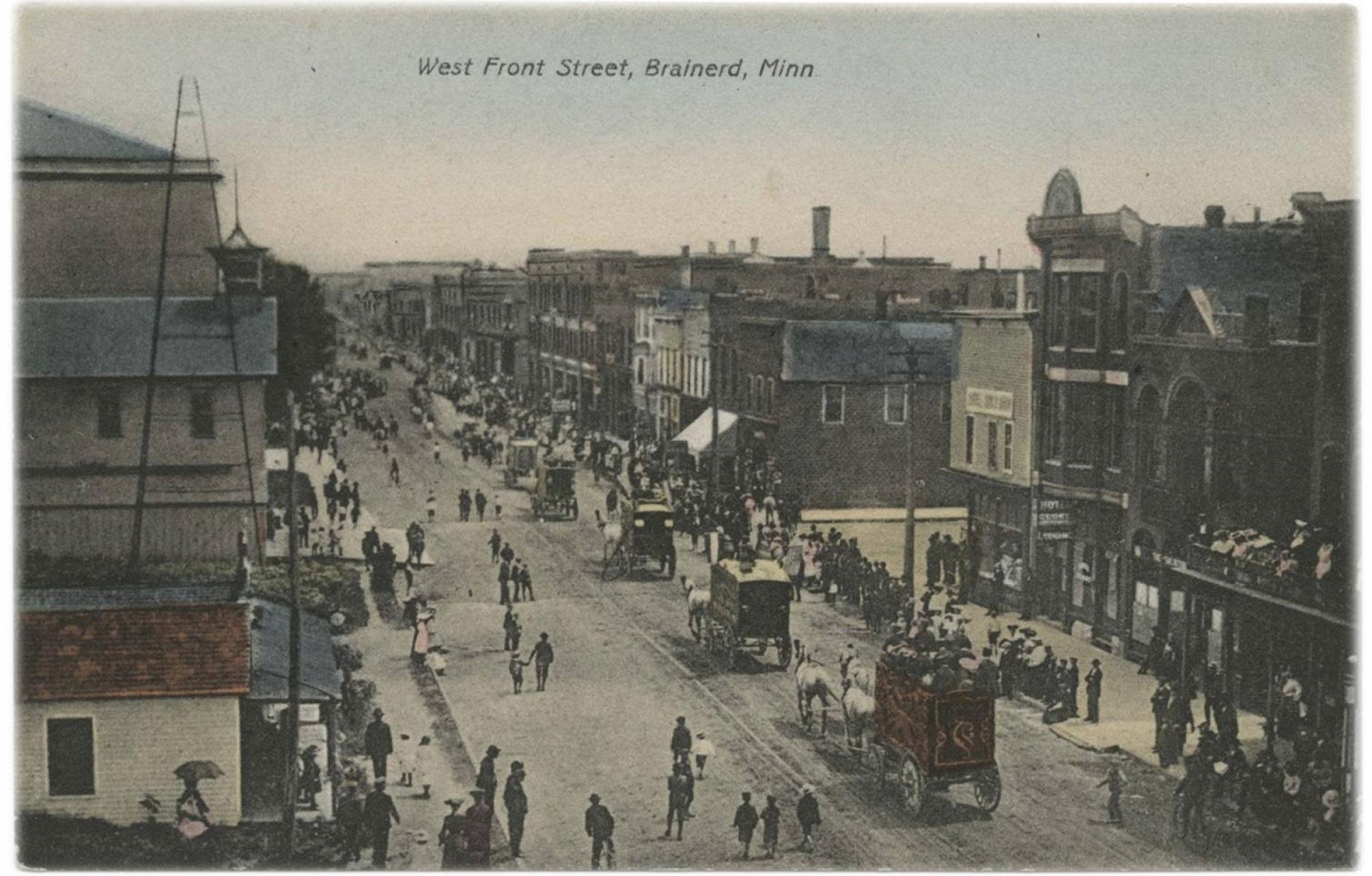

We can fast forward thousands of years, this is my hometown. I live in Brainerd, Minnesota, it’s a couple of hours north of Minneapolis/Saint Paul. This is what it looked like in 1904. People would arrive by train, they would arrive by stagecoach, but when they got there, they would walk everywhere they went. The spacing, the scale, the distances between things people would do on a normal day, all of this was based around a society of people who walked.

Beginning in the early 1900s and then accelerating after World War II, we began to build cities around a different transportation technology: the automobile. We came up with different building types, different building styles, different ways of arranging things on the landscape. If you were to ask people to explain this transition, they would likely talk about it in terms of progress: “We used to build cities around people who walked, now we build cities around people who drive. Someday we will build cities around people in jetcars, and someday we will teleport, and our cities will look completely different than they do today.”

This is a comforting and affirming narrative. It puts us on this continuum of progress. There’s another way to think about this, however, that isn’t quite as affirming. When we look at ancient cities, for example ancient Ur, by the time you get to that period, humans had been experimenting with how to build cities for thousands of years. They tried things; what worked they would incrementally expand upon. What didn’t work, those places went away, those people died, those ideas weren’t transmitted to the next generation. By the time you get to ancient Rome, we have a pattern of development that had been honed over many generations of experimentation. By the time you get to my hometown in the early 1900s, while the building materials might be different, the cultural style might be different, the architecture might be different, the essential layout and design pattern of cities all over the world is virtually universal. Knowledge gained through trial and error [and] experimentation.

When we look at this development style, our 20th Century experiment in a way to build things, we have to understand that this is a very recent phenomenon. When I was an engineer and I would ask questions, I was often told, “This is just the way things have always been done.” But this isn’t the way things have always been done. We didn’t try these out for a couple hundred years to see how it worked, we didn’t go to, pick five states, we didn’t try it on Pennsylvania and see what those crazy people did with this, and then took the best ideas and brought them here. What did we do? We transformed an entire continent all at once, around a new set of theories. We are living in one of the greatest experiments that’s ever been attempted. Not only is this an experiment in how we live in places, but in how we interact with each other, socially, culturally, politically, economically.

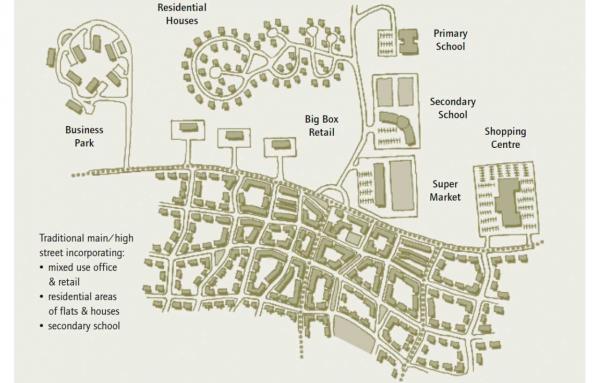

Here’s an example of a closed-loop system with a dead-end cul-de-sac, no through traffic, no commercial traffic, built in the early 1980s. The developer paid all the costs of the road and the street, the sidewalks, the pipes, and then built the homes. The infrastructure was given to the city to maintain. The city collected taxes from these property owners, while the property owners paid their mortgages, which included the value of all this infrastructure.

This road had completely fallen apart. The city went out and did a maintenance project. The cost was $354,000. We asked the question, “based on the taxes the city collects from the people who live within this development, how long is it going to take the city to recoup the money they just spent?” The answer is 79 years. The roads aren’t going to last anywhere near 79 years. So we said, “all right. If the city wanted to recoup enough money between now and the time this road falls apart again, from these property owners, the only ones who use this road in any substantive way, what would that mean?” It would mean an immediate 46 percent increase in taxes, with annual increases of 3 percent over inflation every year for the next 25 years, with all that money going just to maintain the roadway. The sewer, the water, the storm sewer are vastly more expensive undertakings.

Here’s another example, this time business park. It’s one of those typical build-it-and-they-will-come investments that cities of all sizes like to make. The public put in wide industrial streets, deep pipes in the ground, and we try to attract new business growth, built in the mid-1990s. Every single lot has been developed. The city felt it was so successful, they wanted to build the exact same thing in the exact same design on property they owned right next door. We said, “If we could build the exact same thing at the exact same cost, with the exact same amount of investment, would this be a good project for us?”

In today’s dollars, it would cost $2.1 million. There are $6.6 million of assessed improvements out in the business park. Of the improvements, four of those belong to a church, two of them belong to the school district (it’s a bus maintenance building), one of them is a city maintenance garage, one of them is a county maintenance garage. These are all important facilities because we need churches, schools, and maintenance buildings. None of them pay any taxes to the city. Of the remaining lots, the ones that would theoretically pay taxes, every single one was given a tax subsidy in order to attract them to move into this park. For the sake of our analysis—and this is the only way that the math came close to working—we assume that every single lot in our new park would be built on within 12 months of us completing its construction, by a full taxpaying non-subsidized entity, and that every penny of new revenue coming in would go to paying off that debt. If that were the case, it would still take us almost three decades, 29 years, to break even. That’s 29 years when everybody else’s taxes would have to go up to plow the snow, mow the ditches, provide police protection, fire protection, and every other service that was needed, and that’s in a wildly, wildly optimistic scenario.

Let me show you what’s going on; Let’s say that a developer comes to our community and says, “I have a piece of property here I’d like to build upon. I’m willing to build all the homes and commercial properties myself. I am willing to follow all of your rules. I’m not asking for any variances or any handouts or subsidies. I am willing, at my expense as a developer, to pay to put in the roads and the streets and the sidewalks and the curbs. I’ll put in the pipes and the pumps and the valves and the meters—I’ll do all that to your standards. I will pay for that myself. The only thing I am asking as a developer is that when I get done making this investment in your community, that you, the local government, the community, agree to take over and maintain this stuff.”

That sounds fantastic! We spend nothing, you spend everything, we get this huge growth in our tax base, this is fantastic, we would love to do this. But let’s say that we’re smart, prudent people, and we’ve heard the Strong Towns arguments. So, we’re going to take the portion of development revenues that would normally get siphoned off and spent fixing stuff around the city, we’re going to set that portion aside and allow it to accumulate. This is what that looks like:

In Year One, everything is brand new, it hasn’t cost you anything. The money comes in, you set that portion aside. In Year Two, more money comes in, you add it to what you had in Year One. In Year Three, you add a little bit more, and so on. You can see—the money comes in and it’s great. A five-year-old road doesn’t cost you anything, a ten-year-old sidewalk isn’t costing you anything, a fifteen-year-old pipe isn’t costing you anything. And so, you get out a couple of decades, and all you’ve experienced is positive cash flow, money coming in, nothing going out. But when, in this example, you get to Year 25, and you have to actually make good on that promise you made a generation ago, what you find is that the cumulative amount of money you brought in is insufficient. From a cash flow standpoint, you run far into the negative.

Now, cities aren’t one development; cities are a series of developments, a collection of neighborhoods. Let’s say that, a couple of years after that first development goes in, our developer comes back and says, “you know, that worked out really well for me, it worked out well for you; I would like to do a similar-sized development.” And every other year from this point forward, a developer walks in the door [each] with a similar sized proposal. In other words, the ideal scenario for any city, nice, steady, continuous growth. And we take this money coming in, and we set it aside, and we save it for the day when we have to make good on all these promises we’re making as we grow. Here’s what that looks like.

In Year One, you’ve got your first development comes in, it pays in the entire 25 years shown. In Year Three you have your second development, Year Five you have your third, and you can see, not only are you having growth upon growth upon growth, but you don’t have any expenses at all. Your cash starts to accelerate upwards, you’re feeling very rich. And when you get to Year 25 and you have to make good on that promise you made way back in Year One, you gotta spend a little bit of money, but it’s not a big deal, right? You’ve had all this growth. The growth creates what we call the illusion of wealth. Because as we all intuitively understand, if you lose money on every transaction, you don’t make it up in volume.

The further you go out in time, the more downward pressure there is on your budget. This is the answer to the question that plagued me in my engineering years: How are we investing all this money, how are we spending all this money to do all these huge projects, yet our cities are fiscally strapped? How can we not find the money to keep the library open past 4:30? How can we not find the money to keep the streetlights on overnight? How come there’s $9 million available to build a bypass around the south side of my town, for just the peak traffic during the morning five-minute rush? But we can’t find the money to actually maintain the park?

What’s the answer?

Back to my hometown. When I first saw the photo at top, I couldn’t believe it was my city. It looks nothing like this today. I was astounded by what these people had built: The way the buildings line up, the way they frame the public realm at just the right ratios. There’s great segmentation of the space; the buildings have great symmetry, they front the street in a perfect way. This is a street that CNU people would design today, and we would travel across the country to look at. Let me ask you some questions about the people who built this. How thick was their zoning code? How many boards and committees did they have to go to, to get approval to build something? How many grants did they receive? How much tax subsidy did they hand out? How many shovel-ready sites did they have? How many Amazons and Googles came trawling through town, looking for stuff. We can go through the litany of things that we have convinced ourselves are absolutely essential to building great places; these people had none of them. They didn’t have engineers and architects and planners, they didn’t even have 30-year mortgages. How did they build such a spectacular place? It’s really simple: they copied what they knew worked. They took the materials they had on hand, and they built in a style and an approach that they had seen work for thousands of years around the world.

After 70 years of advice from planners and engineers and economic development advisors, after all the programs and investments to create jobs and growth and economic development, after all the subsidies and things we’ve done to juice our economy, here’s what this exact same street now looks like.

For a long period of time, that illusion of wealth made us think that this kind of thing didn’t matter. We could run roads and streets and highways all over the place; we could have interchanges. We could have pipes with nothing on it. We could have huge gaps in our system and none of it mattered. We were so rich, we didn’t bother to ask the obvious question: Where’s the wealth to take care of this stuff?

I’m going to show you right now the very simple way that cities build well.

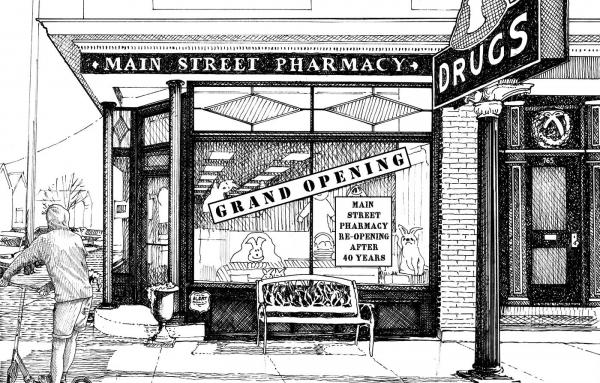

We built thousands of these across this continent. What happens when a place like this fails? Does the stock market crash, does unemployment skyrocket, do we have an emergency session of Congress to bail out banks? No. These are small little bets. A few people lose a little bit of money, they salvage what they can and they move on to the next place.

A lot of these places were successful, and they would grow in a very simple-to-understand way. They’d grow incrementally up, incrementally out, and become incrementally more intense. After 30 years of incremental development, this street, which is in my hometown in 1870, would become the street at the top of this article. And after another 40 years of growing incrementally, these two- and three-story wood structures would be replaced by buildings of brick and granite.

We don’t build wealth by going to the casino and putting it all on red. The way that cities build wealth is by making modest investments over a broad area over a long period of time.

The Lafayette story

Joe Minicozzi, a friend and collaborator, is known for these beautiful maps his team puts together. Joe’s team and I got invited to Lafayette, Louisiana, to help them understand and communicate why they were experiencing so much financial distress. A huge backlog of road maintenance that grew every year, they did not have the money to take care of everything, and they were having a really difficult time understanding why and explaining that to people. They asked us to analyze and help explain it to staff and to the community. We dug through all of their financial records, we looked at every expense, we interviewed the department heads, we looked at all their revenue sources, we created dozens and dozens of maps and mashed them all together into one map that described the cash flow situation of Lafayette, Louisiana. Joe’s team puts these maps together. They use red for places that are losing money, green for places that are gaining money.

There’s a big cluster of green in the center of this map. That is Lafayette’s core downtown. I like Lafayette’s downtown, but let me just give it some context. There’s nobody who visits Lafayette, Louisiana, who is taken downtown to experience the ambiance or take photos. It’s not that kind of place. But yet financially it’s doing really great. There’s a crescent of green that runs just east of downtown. Those areas are also cashflow positive. Those are the poor neighborhoods. Those are the neighborhoods where, when we went to work and were going to get an AirBnB, the city staff said, “just don’t get it in that neighborhood. That’s where the homicides happen, the burglaries happen, like stay away from there; that’s the bad part of town.” Everything else in this map is red. That includes big box stores, strip malls, chain restaurants, and the curvy cul-de-sacs with the three-car garages. This map shows two subsidies that we see in every city across America that we’ve modeled. Subsidy number one: the poor neighborhoods subsidize the affluent ones. That’s a universal condition of the American development path. Subsidy number two: Future generations subsidize today’s generation. The median family in Lafayette makes $45,000 a year. They pay $1,500 a year in taxes to the city—in addition to other taxes to the state, county, parish, and school district. And in order for them to make good on every promise that they have made, to turn this entire map green, taxes would have to go from $1,500 a year to $9,200 a year. One out of every five dollars that the median Lafayette family makes would need to be sent to the city just to maintain the stuff they currently have. That would never happen. There’s no chance of that ever happening. And so Lafayette faces the problem of deciding, “what streets do we maintain, what streets do we let go? What pipe do we fix, what pipe do we walk away from? What neighborhoods do we cling to and what neighborhoods do we let fall apart?”

Above is another graphic, which shows value per acre in High Point, North Carolina, including Kmart out on the edge, at $384,000 an acre, and Walmart at $967,000 an acre. I won’t go through all the subsidies they paid to attract this development, but I will switch to the core downtown where there's an old warehouse that’s been converted into a supper club at over $5 million an acre, and my favorite place of all, Jimmy’s Pizza: $3.4 million an acre, below.

Look at Jimmy’s Pizza. When I go around the country and I show them this, the reaction I get is “We aspire to great things, we don’t aspire to that.” But yet, when we actually do the math, if we had a city of Jimmy’s Pizzas we’d be a rich place. When you experience an American city today, at 30, 40, 50 miles an hour, you don’t grasp—like you grasp clearly at 2 miles an hour—is that our cities are nothing but gaps. Try walking between places; it is nothing but space. As an engineer, when I walk those spaces, I’m thinking to myself, “okay, a thousand dollars a foot, bam, bam, bam, bam. We just spent $200,000 and there’s nothing here.” From your car, that doesn’t register. We have to actually humble ourselves to realize the potency and the potential of a Jimmy’s Pizza. Because as we’re talking about incrementally building cities, and dealing with cities that are trending toward functional insolvency, we can’t go in and spend a bunch of money. We need to start building things that actually work. And we start at the next increment of improvement, that being a small little box.

Here’s the crazy thing about this: This is not hard to grasp. When we build things like Kmart and Walmart, where do the profits for this place end up? Where does the money that we spend here go?

When we build a Jimmy’ Pizza, where do the profits end up? Jimmy’s a guy that hires a local accountant, banks at the local bank, hires the local ad agency and runs ads in the local paper. Jimmy has a float in the Fourth of July parade. Jimmy volunteers on the PTA. His kids go to your church with you, they go to school with your kids.

When we’re talking about incrementally growing cities, a Jimmy’s Pizza strategy becomes critical. It may seem beneath us today. It may seem petty for a global economy. But our cities are broke; we have to actually start thinking differently.