Crash diet for a freeway corridor

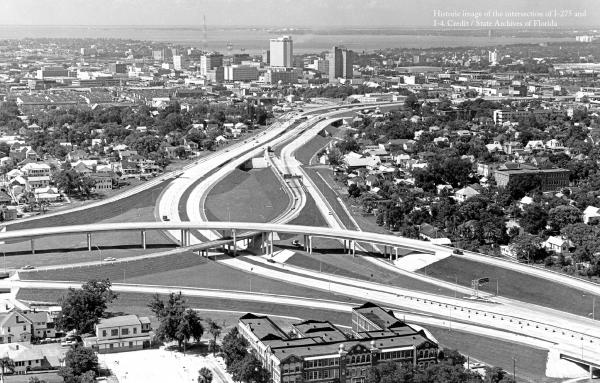

I-980 remains a testament to the intense disapproval for freeway construction at the end of the highway-building era. Public opposition to its construction was so strong that the project was abandoned in 1971, only to be resurrected and finally completed over a decade later. Now, the excessively wide highway prevents West Oakland from enjoying the revival experienced by Uptown Oakland, the neighborhood on the opposite side of I-980 and its parallel frontage roads.

The economic benefits promised as part of this highway’s construction failed to materialize. Instead, the West Oakland neighborhoods adjacent to I-980 experience some of the highest asthma rates in the state of California (in the 99th and 100th percentile) and have notably poor access to healthy foods. Meanwhile, less than a quarter mile away across I-980, Uptown Oakland is undergoing a renaissance. West Oakland residents should be able to walk to Uptown’s services and amenities, but are effectively cut off by a daunting route that consists not only of the Interstate highway, but also a pair of frontage roads that serve fast-moving traffic. The right-of-way for all of this asphalt is an enormous 560 feet wide.

Caltrans acknowledges that the current number of lanes is excessive to accommodate the 92,000 cars per day that travel the road, a volume that accounts for only 53 percent of possible capacity. Most of these vehicles are local traffic, with both origins and destinations along the northern part of the corridor. Most trucks that prefer wide lanes to service Oakland’s port already opt for I-880 over I-980. A surface boulevard integrated into a street grid along the route of I-980 would have the capacity to handle the traffic in a more suitable fashion.

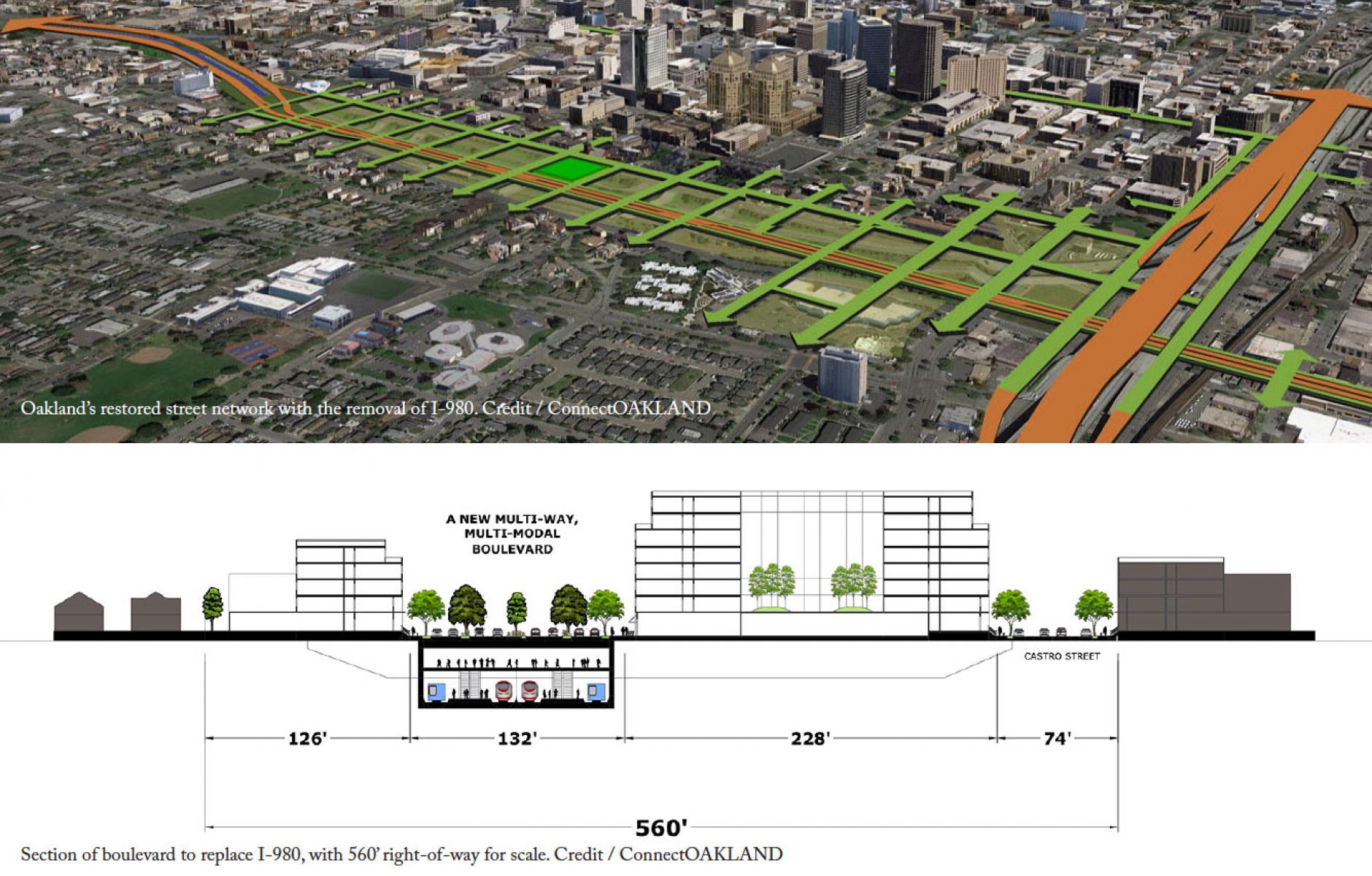

The citizen group ConnectOAKLAND calls for replacing I-980 with a boulevard that has capacity for transit and bike facilities. The I-980 footprint has the potential to build a strong foundation for regional mobility, especially if connected to existing public transit networks like BART and Caltrain. ConnectOAKLAND’s vision includes taking advantage of I-980’s depressed lanes to create multi-level transit infrastructure and avoid costly tunneling or seizure of private property. The right-of-way for the proposed boulevard would be 75 percent narrower than the highway, making pedestrian crossing easier.

The transformation of I-980 offers other important benefits for the city. The creation of a boulevard will stitch the former street network back together with as many as 15 cross streets and, in the process, create new real estate adjacent to downtown. The boulevard solution reclaims seven western blocks that I-980 encroached upon, and creates 14 new city blocks to the east—around 17 acres in total of publicly controlled urban land. This new land could be developed for any type, use, or intensity that will best serve the interests of Oakland’s residents, including affordable housing and community services.

With this proposal in hand, ConnectOAKLAND has engaged private, public, and professional stakeholders. Many local leaders and community activists in West Oakland support the plan and Mayor Libby Schaaf has championed the removal of this underutilized section of highway. The City of Oakland is now exploring the replacement of I-980 with surface streets as part of its Downtown Oakland Plan. Although much work remains to be done, the removal of I-980 would advance many community goals while opening up opportunities for equitable development.

Note: CNU's sixth biennial Freeways Without Futures report was released April 3, and I-980 was one of ten projects on the list. Freeways will be a topic at CNU 27 in Louisville June 12 through 15. Discounted registration is available until May 10th.