Design

Mid-rise residential buildings are an essential component of urbanism when they respond to context and help set the pattern of streets and blocks.

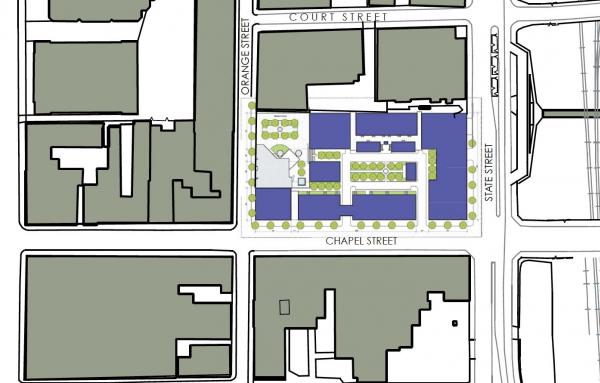

Giant surface parking destroys the geometrical coherence and pedestrian connectivity of a campus. The solution lies in limiting the width of the parking without reducing the number of parking spaces.

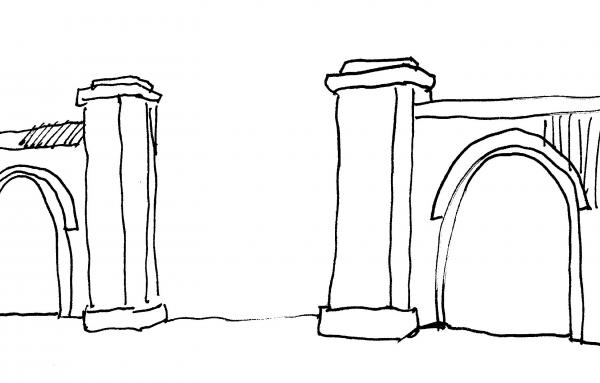

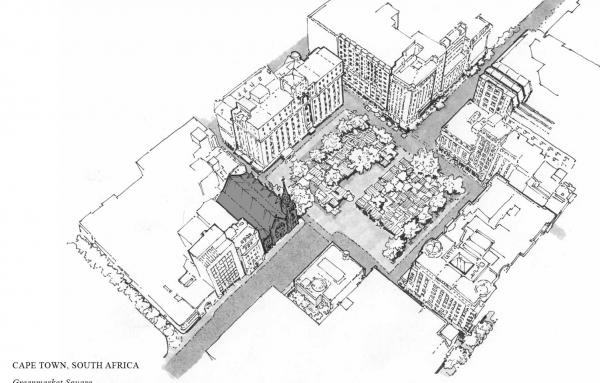

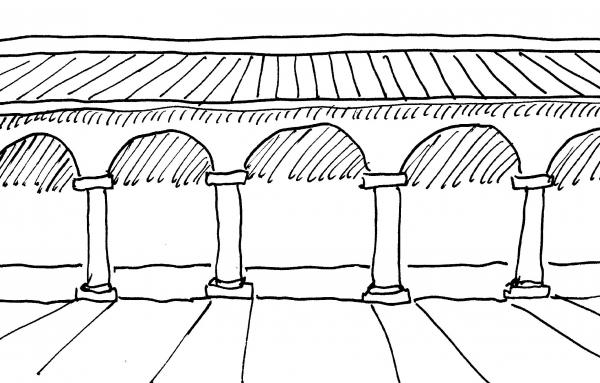

The boundary of a physical space counts for a major part of our spatial experience. Several distinct typologies for spaces contribute to a campus environment that is actively used.

Open space will be used when we feel that it encloses us with a semi-permeable, welcoming perimeter. The design of successful urban space therefore relies predominantly on human psychological responses.

Fundamental sensory mechanisms determine how we walk in relation to built structures. This physiological basis must inform the design of pedestrian campus circulation.

In Curridabat, Costa Rica, new urbanist interventions are combined with park improvements, wetlands, and projects to improve biodiversity.

Identifying mistakes in designers' basic assumptions is a first step to a healthier, more sustainable built environment.

Institutions face a fierce opposition between living campus environments that look old-fashioned, and contemporary architectural expressions, which do not contribute to emotional and physical wellbeing.

In Charlottesville, Virginia, 12-acre linear park incorporates stormwater systems into community spaces that allow for new development.

The project inverts the usual relationship between car and human in land development.